Life by itself is formless wherever it is. Art must give it a form.

– Hugh MacLennan, Two Solitudes (1945)

The historical events we remember can be very revealing, not least because recollection is not a pure, spontaneous act. Collectively, it is a response to present-day concerns and the result of careful selection by well-placed elites—politicians, religious figures, teachers, and interested business leaders. The past is largely shapeless, providing examples of everything under the sun. But history and public memory, like art, are given a form by people with an agenda. (Often, both because and in spite of historians’ best intentions.)

In the case of Quebec, we can trace the first major effort to create history back to the second half of the nineteenth century—where we again cross paths with Prosper Bender (1844-1917). (See here and here for background.)

Bender, a Quebec-born physician and writer, has himself been history for over a century, yet the literary movement with which he engaged continues to say a great deal about the role of the past in the construction of a Quebec identity.

Bender spent much of his later years recollecting, for readers of the Daily Telegraph, the famous figures and cultural life of Quebec City in the 1870s and early 1880s. As he neared his three-score and ten, he naturally looked more easily to the past than to the future and sought to honor his many dear, departed friends.

An even closer look at his work suggests that he in fact spent much of his life looking back—as did his friends and fellow writers in the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s.

Unlike the most influential French-Canadian historian of the century, François-Xavier Garneau, writers in Bender’s circle were not primarily motivated by Lord Durham’s famous allegation that the French-speaking Canadiens were “a people with no literature and no history.” But they tended to both of these fields with immense vigor.

With the new economic and political opportunities of the 1850s, the influence of American letters, a growing reading public, and a proliferation of periodicals, Canadian littérateurs found ample means and inspiration to support their writing. The bookstores of Charles Hamel and Octave Crémazie became centers of creation that together drew such luminaries as Garneau, James MacPherson Le Moine, Philippe-Joseph Aubert de Gaspé, historian J.-B.-A. Ferland, Bender’s friend Hubert La Rue, the venerable editor Etienne Parent, Antoine Gérin-Lajoie, Superintendent of Education P.-J.-O. Chauveau, poet Louis Fréchette, and Father Henri-Raymong Casgrain.

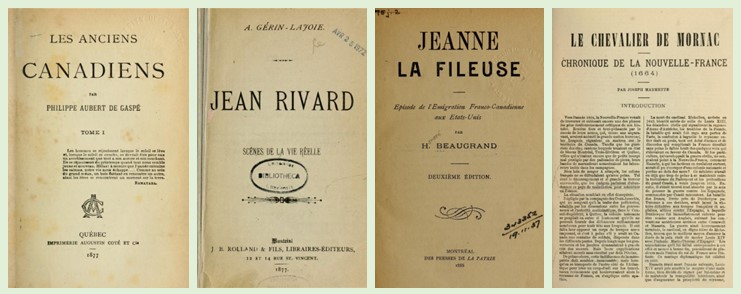

Casgrain recorded French-Canadian legends and edited the premier literary magazines of the day, Les Soirées canadiennes and Le Foyer canadien. Ferland, a fellow priest, published the first tome of his Cours d’histoire du Canada in 1861. Aubert de Gaspé published Les Anciens Canadiens (1863-1864), which wrapped personal recollections, historical events, and romance in a twenty-year storyline that centered on the Conquest of 1759-1760. Whereas much of the French-language writing of the time was at least indirectly political, the author was far more dedicated to the preservation of the customs of prior times. (Aubert de Gaspé was in fact by then almost eighty.) It was in these same years that Antoine Gérin-Lajoie, a protégé of Ferland and a writer otherwise known for Un Canadien Errant, published Jean Rivard and its sequel. Somewhat more dogmatic than other works of the time, Jean Rivard foreshadowed the development of the littérature du terroir a generation or two later.

Around the same time, James MacPherson Le Moine, who would play a prominent role within the Royal Society, began to publish a series of works on the customs and history of Quebec, including the multi-volume Maple Leaves (begun in 1863). In little more than a generation after Durham’s passing, French Canadians could claim an elite intellectual and literary life as rich and varied as that of English society in British North America. More significantly, such cultural development was an indigenous phenomenon, not content to replicate the forms of colonial metropoles past and present—nor indeed interested in doing so. In fact, a French writer such as Edme Rameau de Saint-Pierre was as influenced by the body of work emerging in Canada as he, in turn, influenced it.

The early 1870s witnessed new ways of approaching the French-Canadian past. Father Cyprien Tanguay’s Dictionnaire généalogique (1871-1890) began to appear. Louis-Philippe Turcotte wrote a more conventional history, a kind of annale with limited analysis but establishing the political facts of a recent past, with Le Canada sous l’Union, 1841-1867 (1871-1872). This was also a prolific decade for Joseph Marmette, Garneau’s son-in-law, during which he established his reputation as a novelist with François de Bienville, scènes de la vie canadienne au XVIIe siècle, L’intendant Bigot, and Le chevalier de Mornac. Like Aubert de Gaspé, Marmette was sorting out what to keep, what to leave to Quebec’s past, and dramatizing some of its iconic moments. In fact, the historical fiction of Marmette and Aubert de Gaspé sought to recover the essence of an imagined nation canadienne. Poetry, political journalism, and oratory served the same end. Beyond the works of Garneau and Ferland, these would be the essential materials of Quebec’s historical consciousness until the development of history as an academic and professional discipline in the twentieth century. (For readers familiar with Imagined Communities, there is a clear echo here of Benedict Anderson’s work on the building of national consciousness.)

Granted, apparent unity in purpose was broken by the legacy of debates between conservative Bleus and liberal Rouges. Traditional values—the glorification of the Catholic faith and agricultural life—confronted liberalism, anticlericalism, and fascination with American democracy. Some of that tension persisted into the latter part of the century with Honoré Beaugrand and Louis Fréchette, but by the 1870s the traditional, ultramontane ideology was quite clearly ascendant. A new, conservative consensus formed as public discourse narrowed. Evidence of this was seen in excisions and alterations of Garneau’s work in subsequent editions (especially where he had been critical of the Catholic Church).

Le Moine’s Picturesque Quebec (1882) coincided with a new phase of historical writing. Alfred Garneau completed a new revision of his illustrious father’s history in the early 1880s. Civil servant Benjamin Sulte joined the effort by publishing an eight-volume Histoire des Canadiens-Français, 1608-1880 (1882-1884), which placed the greatest emphasis on the history of New France. At last, Prosper Bender’s Old and New Canada (1882) chronicled a century of Canadian history through the life of his own great-grandfather, Joseph-François Perrault. Although Bender was writing in English and brought his own bicultural heritage to historical writing, his salon and subject matter suggest that he was responding to a French-Canadian literary movement. Together, these works closed two decades of feverish historical writing whose precepts would only find a forceful sequel with Lionel Groulx and a new generation of Quebec historians in the twentieth century.

It was in 1882, on the heels of the publication of Old and New Canada, that Bender moved to Boston just as his literary circle was dissolving. As far as can be discerned, his friends went abroad, found new pursuits, or seized opportunities in government. After all, aside from the clergymen, the cultural endeavors of the above writers were a mark of their middle-class status, and it was this class status that led them, indeed enabled them, to seek a sinecure in the civil service. Many did so successfully thanks to political and familial connections. Without prospects in government, and being passed over for Royal Society membership, Bender turned to the United States and continued to write on French-Canadian history, politics, and customs for an American readership.

Looking at those two decades, it is no easy task to distinguish what is history—as we view it—and what isn’t. Historical novels were not meant to convey every specific fact, but certain truths, through verisimilitude; historical specifics provided useful context and characters. The plot of Beaugrand’s Jeanne la Fileuse (1878), for instance, rested heavily on the Patriot Rebellion, a life-altering event for the colony, but also for fictional characters and their literary offspring.

An explanation for this historical writing of a kind does not lie merely in attempts to make up ground relative to the surrounding Anglo-Saxon world. Like its neighbors, Quebec was then experiencing a period of rapid and worrisome change, from the constitution of 1867 to industrialization, from mass migration to the United States to urbanization in Quebec itself. The French-Canadian intelligentsia reacted in an ultimate act of preservation, so that the past might moor present generations and provide them with clear bearings. Much of this, notably through the efforts of the Church, would trickle into policy and politics.

The last two decades of the century witnessed dedicated efforts to colonize the outer regions of the Province of Quebec to forestall the rural exodus and emigration to the United States, promote agriculture, and protect traditional values. The prior generation of historical writers unwittingly provided this movement with steady footing and legitimacy. Nostalgia for an imagined past led to a hasty rejection of economic diversification and any type of liberalism that clashed with clerical authority, or that recalled the revolutions of the prior century. The course was set—and, to a great extent, history became reality.

Bibliographical Note

Excellent portrayals of the authors mentioned above appear in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography; some works are available in their entirety and free-of-charge on the Internet Archive. Essential context may be found in The Canadian Encyclopedia. Other valuable resources on nineteenth-century Quebec literature include Maurice Lemire’s La vie littéraire au Québec and Jean-Louis Lessard’s terrific blog. At last, you can learn more about Bender in “Seeking an ‘Entente Cordiale’: Prosper Bender, French Canada, and Intercultural Brokership in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Canadian Studies (spring 2018), 381-403, accessible here.

I just read a number of your articles. Great stuff! congratulation.

Thank you, Bernie, that means a lot!