War and peace. A pandemic. The League of Nations debate. Nationwide women’s suffrage. Prohibition. Unending strikes and the Red Scare. Runaway inflation and a deep recession. Race riots. Intense Americanism (read: xenophobia), and proposals for English-only education and immigration restriction. And more.

From 1917, the United States experienced rapid transformations that revolutionized—at least for a time—citizens’ relationship to the government and to one another. Americans (both the “old stock” and minority groups) worried about their livelihood and the fate of their culture and institutions. As troubled as 2020 has been, it doesn’t hold a candle to the disruptions and anxiety that followed the First World War.

Franco-Americans felt those transformations acutely. They took part in major strikes that rattled various industries in 1919 and 1922. In some states they were the primary targets of Americanism and English-only elementary education. Growing surveillance of the northern boundary and high-profile events at the border led to associations between French-Canadian migrations and criminality.

One overlooked story from this period is Franco-Americans’ ability to forge new partnerships. At this moment of crisis, they rediscovered old allies. The Catholic bishops of the Northeast (many of Irish descent) generally opposed state-mandated anglicization programs. Catholics banded together to challenge proposals for the centralization of education, health, and welfare services. In many communities, Franco-Americans and their Irish coreligionists teamed up to beat back intimidation by the northern Ku Klux Klan. All the while, Francos warmed up to a labor movement still led by the Irish and their economic and cultural concerns led them into the Democratic fold, whose face was also Irish.

We should take care not to overstate the extent of this alliance—which was strategic, ad hoc, and self-interested. It was a marriage of convenience in certain areas of public life, not wholesale cultural fusion. But both groups benefited from this kind of collaboration and in the process they developed a different kind of Americanism.

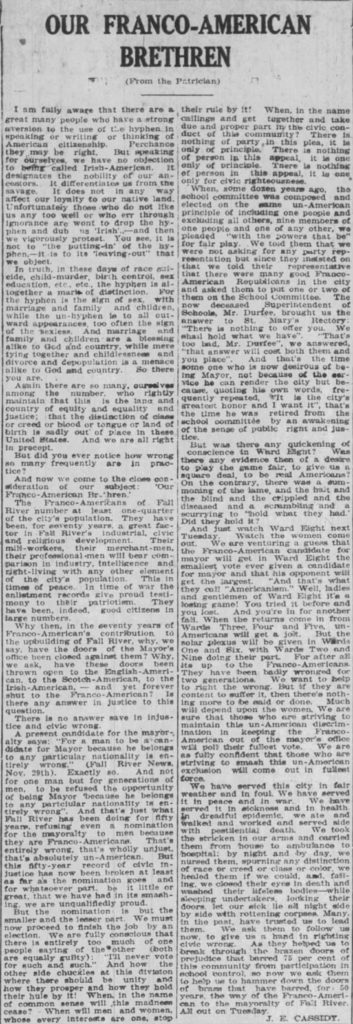

In many parts of the Northeast, Francos’ increasing identification with the Democratic Party earned them recognition and an ever-growing presence on party tickets. Some Irish Americans were willing to concede that their French-speaking neighbors’ time had come. So said J. E. Cassidy on the eve of Fall River’s municipal election in 1922. Edmond P. Talbot—Democrat and Franco-American—was running for the mayoralty and, if elected, he would be the first Franco in that position.

Talbot won—and made history.

Cassidy’s views, published in the Fall River Globe, are, as we see early on, very much a product of their time. Still, it is a case that continues to resonate almost a century later.

Leave a Reply