As some of you know, in the last few months, I have compiled all debates of the Quebec legislature that addressed (or mentioned) emigration and repatriation between 1867 and 1900. In making these debates more accessible, I hope they will draw the attention and interest of other researchers, thus bringing more voices into the historical conversation and broadening our understanding of the subject.

There are a lot of layers to these debates and, having pored over every word, I thought I would share, in all-too-brief form, some of the important stories weaved through discussions of emigration.

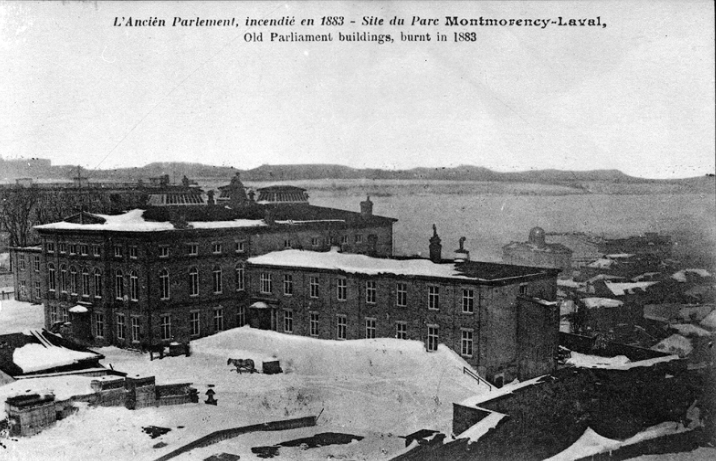

1. The physical setting: Quebec City

By 1867, Quebec City had entered a period of economic decline. Ottawa was confirmed as capital of the new dominion, taking with it not only prestige and influence but a small army of civil servants. The lumber industry that had helped support the city earlier in the century had itself been in decline since the 1840s. People left. Thanks to its proximity to Ontario and the United States and its railway connections, Montreal emerged as the province’s primary commercial center. Industrialization radiated from Montreal, whereas only small-scale light industry grew in Quebec City—and that wasn’t enough to turn the latter’s prospects. Quebec City also faced devastating fires, one of which, in 1883, gutted the old parliament building on the côte de la Montagne. Construction on the current Hôtel du Parlement began soon after. That was not the end of the excitement. In October 1884, with construction ongoing, some unknown individuals detonated dynamite inside the new structure. Political violence had returned to Quebec. The culprits were never found.

2. Dynamite of a different kind

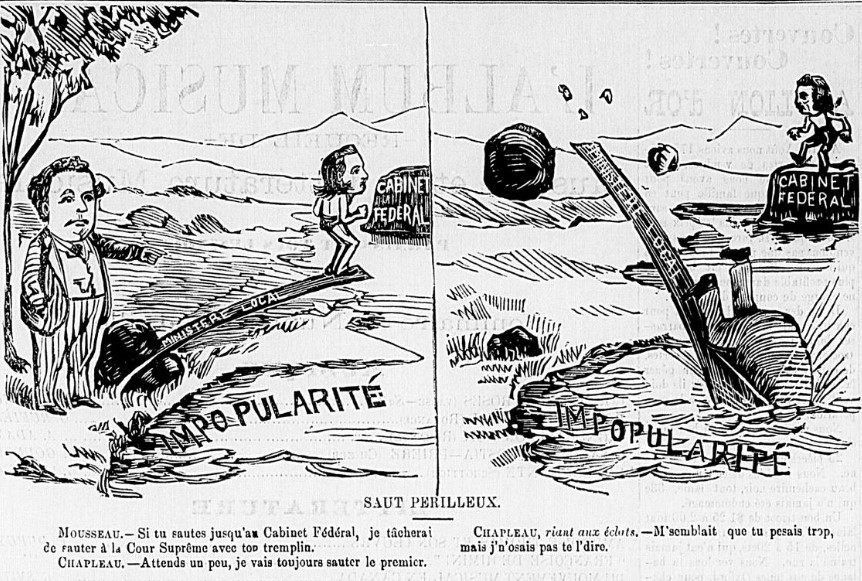

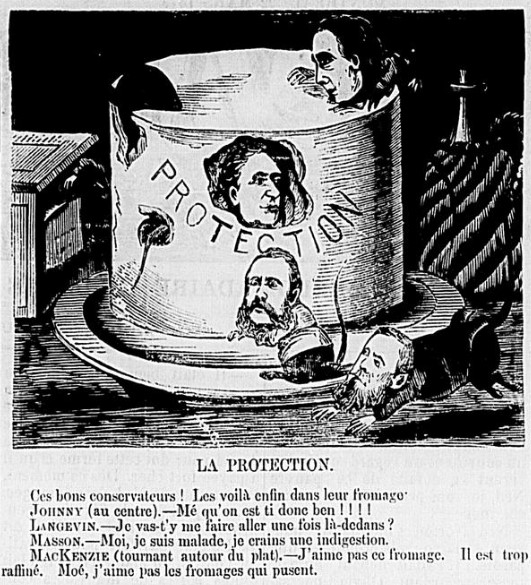

Quebec’s history curriculum and public memory tend to brush broadly over the second half of the nineteenth century. The province seemed to have entered a prolonged period of conservative ascendency. The triumphant Catholic Church ensured stability from the world of politics down to the predictable rhythms of the rural parish. But the rural world changed considerably—and the political sphere had its share of tremors. Kickback scandals tarnished three premiers in less than two decades. The Pacific Scandal in Ottawa reverberated in the provincial capital. The North-West Resistance and Riel affair announced a partisan shift. The legislature witnessed heated partisan debates with MLAs always very sensitive to slights or challenges to their honor and reputation. The Opposition—Liberal or Conservative—was quick to allege that funds for roads or colonization were awarded along partisan lines, with counties voting the right way getting the lion’s share. All that is to say that the legislative assembly regularly witnessed figurative explosions.

3. Who’s who

In his early years in the assembly, Félix-Gabriel Marchand was very active in advocating measures that would promote repatriation or protect repatriates. A colleague called him the leader of the 500,000 French Canadians in exile and—light-heartedly—wished him the honor of becoming their governor. Another Liberal, Mercier, as we’ve seen on this blog, constantly reached out to Franco-Americans, whether the latter liked it or not. But a look at the provincial premiers doesn’t tell the whole story. Jacques Picard (Richmond and Wolfe), Jérôme-Adolphe Chicoyne (Wolfe), Guillaume-Alphonse Nantel (Terrebonne), and successive MLAs from the Lac-Saint-Jean region very often connected emigration to colonization. Faucher de Saint-Maurice (Bellechasse) outdid most of them. By his general interest in the Franco-Americans’ conditions, his expressions of friendship, and his many trips to the U.S. Northeast, he was in many respects Mercier’s Conservative counterpart. In 1883, as a freshman legislator, he led the vigorous response to the Frank Foster controversy; he was still at it in 1890, when he delivered a long exposé on Franco-American life.

4. Patrons of industry?

In the late 1860s and 1870s, the legislature debated how best to accelerate industrialization. Many MLAs saw this as an opportunity to retain French Canadians who were going to work in American factories; they discussed commercial tariffs, direct subsidies to industry, railway construction, etc. Those legislators argued that the province’s future prosperity depended on both industrial and agricultural progress. The tone during the last two decades of the century was quite different, and the legislative record offers hints as to why that might have been. The depression of the 1870s exposed the hardship caused by the industrial boom-and-bust cycle. The Macdonald federal government took a more assertive stance with regard to tariffs, which it envisioned as the ultimate industrial panacea. Costly railway projects nearly bankrupted Quebec. And news stories from the U.S. and Europe showcased the unrest and moral turpitude that seemed to accompany urban life. Agricultural colonization instead held the key to economic salvation, if not salvation of an altogether different kind.

5. Agriculture past and present

Legislators did not see Quebec’s countryside as a static pastoral setting. Through the late nineteenth century, they constantly sought to establish a thriving commercial agriculture, and that required education, innovation, and a search for new outlets. Plans for large-scale sugar beet operations proved to be a bust. But other measures helped establish Quebec agriculture as we know it today. Support to cheese and butter production ensured the viability of dairy farming; the government took interest in agricultural colleges; the first cercles agricoles, promoted by Chicoyne, served as low-interest lending institutions and presaged the longer-lived caisses populaires; and, in the 1890s, experts called for grain silos that would better preserve livestock fodder, corn in particular—and so came bigger herds and increasing corn acreage. But those changes could only come gradually. Requiring capital, they weren’t much of an opportunity to farmers or farm laborers in need of liquidity—which often could only be accessed in American factories.

6. Whose land should it be?

In the 1880s and early 1890s, some of the longest single-session debates revolved around lumber reserves. A Conservative government allocated large expanses of the province to lumber interests in 1882-1883—one possible engine of economic growth. To promote colonization, Premier Mercier reversed the policy and prioritized individual grants for farming purposes. However, on such parcels, lumber companies could still remove all commercial timber in the first thirty months from the date of the grant. This gesture, meant to satisfy the companies while signaling the government’s dedication to the cause of colonization and repatriation, ultimately satisfied no one. The other big question regarding land was whether it should be granted without charge to the settler (although certain conditions would have to be met), as was the case under the United States’ Homestead Act. When pressed for free grants, government spokesmen replied that the sale of Crown Lands was one of the most important—and one of the few—sources of revenue at the provincial level.

7. The Belgians are coming!

Okay, that didn’t really happen. Nor did plans to attract large numbers of displaced people from Alsace-Lorraine (after 1871) or farming families from the western parts of France. Joint federal-provincial control over immigration meant that Quebec had an opportunity to recruit abroad and seek out its ideal newcomer. The famed curé Labelle was sent to France on the federal government’s dime in the 1880s and many hoped a steady stream of immigrants would then take up farms abandoned by those going to the United States. The provincial government, for its part, pledged that it would bring over upstanding French-speaking families who could in fact farm—and not troublesome workers from Paris. Such efforts failed. Of Europeans who came to Canada, many simply took advantage of subsidized transportation before moving on to more alluring opportunities in other regions of the continent. As some policymakers had worked out as early as the 1870s, Quebec had little chance of retaining those newcomers if it couldn’t keep its own people from crossing the border.

As you might suspect, most remarks offered to the legislature in the course of these debates were in French. The compilations are available in their entirety, free of charge, on Archive.org. The first covers the first thirteen years of Confederation; the second runs to the end of the nineteenth century. By the time of Marchand’s government, the issue of emigration was drawing very little attention.

May is the month of Maine on the blog. Return in two weeks for the story of the Madawaska region.

Leave a Reply