For more on Franco-American history, please check out the following links:

- Franco-American political history from our friends at the French-Canadian Legacy Podcast;

- A history of religious and public education in the St. John River valley on the Acadian Archives blog;

- An essay on the “prehistory” of the great migration from the St. Lawrence River valley (available from the American Review of Canadian Studies with institutional access);

- French-Canadian participation in the California gold rush in the latest issue of Le Forum (winter 2021-2022).

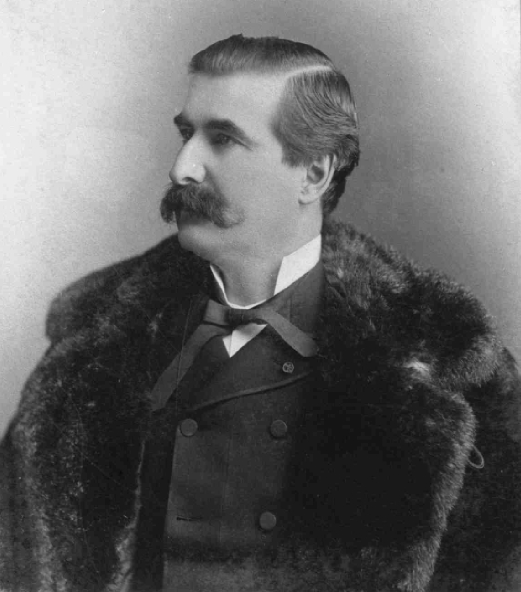

A staunch proponent of Métis claims on the Prairies, Louis Riel was not always a Canadian national hero. Nor was he always celebrated as a French-Canadian icon—a convenient erasure of his Métis identity—as he is today.

According to the contemporary French-language press in Quebec, by June 1885, Riel was guilty of two seemingly unpardonable crimes. He had led the Métis and First Nations in revolt against the settler society that laid claim to the Prairies. This meant striking against the central government that still bore the stamp of equal partnership between “founding races,” i.e. French and English. Quebec’s Conservative delegation in Ottawa was vital to Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s power; what’s more, in the early 1880s, elites in Quebec still dreamt of the Prairies as a safe outlet for the tide of outmigration from the province. They bought into the nation-building project that entailed the displacement of “half-breeds” and “savages.” Riel did not simply imperil this political and colonial enterprise, however. He also posed a religious problem.

An article first published in La Minerve on June 1, 1885 and reproduced in La Presse stated that Riel “had established a new religion, wishing to become a kind of Muhammad or Mahdi. As the priests were opposed to the insurrection, he determined that he could do no better than to put himself in their place and to give the ‘Métis nation’ a religion that would be unique to it. It is unbelievable, yet nothing could be more true.” By adopting the name David, Riel seemed intent on establishing himself as a prophet. Not surprisingly, many Catholic clergymen perceived his providentialism to be dangerous.

French Canadians would later reconcile Riel’s political and religious crimes with the appeal for clemency by claiming that the Métis leader was insane—a plea that his attorneys made, during his trial, in spite of Riel’s own protests.

Quebec newspapers also celebrated the campaign of the Montreal-based 65th Battalion of Canadian militia and its commanding officer, Lt. Col. J.-A. Ouimet. French-Canadian soldiers and officers earned their share of praise.

Riel was captured in late spring and brought to trial in Regina in July. As historian Mason Wade explained in his magisterial work on French Canadians, that’s when another kind of trouble began. “Gradually the question became not one of Riel’s guilt or innocence,” Wade noted, “but the execution or pardon of a compatriot.” During the summer of 1885, English and French Canadians projected their fears about Confederation, which had just faced its biggest trial, on the entire Riel affair. French-Canadian worries focused on the English-Canadian jury and the Macdonald government’s unwillingness to seek clemency. Dismissing claims of mental alienation, some in the English-language press believed a treasonous spirit extended to all French Canadians who called for Riel’s exculpation. In the wake of Riel’s hanging, public figures in Quebec claimed they too would have raised arms against the government had they lived in Saskatchewan. The historical record actually shows that they had little sympathy for the revolt, even for the claims of Indigenous groups west of Ontario, in the spring of 1885.

French Canadians’ anger was fed by the ravages of a smallpox epidemic—in which ethnic tensions also played a part. The English-language press made hay of the spread of disease in the Province of Quebec. La Minerve protested. It stated that English Quebeckers were also touched; the virus had, what’s more, come from Chicago thanks to a Yankee traveler. “But the Francophobic press conveniently omits this fact,” the paper declared on September 7. “It prefers to go after the victims of the American variola, after our poor compatriots, who have committed the supreme error of not belonging to the superior race of Anglo-Americans.” Evidently, journalistic takes on the epidemic compounded existing resentment and tensions.

The political consequences of Riel’s trial and execution were extensive in Central Canada. But ethnic hostility and suspicions on both sides of the Ottawa River derailed the real issue—an issue that is at least now being recognized in Canadian history textbooks. Riel was raising the important matter of self-determination, rooted in an ancestral land claim, for the Métis people and First Nations of the West. It was a question about colonization and colonialism in which English and French Canadians alike were complicit. In the struggle between the two national “solitudes” from 1885 onward, the claims and concerns of Indigenous peoples were buried.[1]

* * *

This sequence of events is not only historical fact, but a parable for the present-day debate surrounding Quebec’s Bill 21 (Loi sur la laïcité de l’Etat). The law, introduced and passed in 2019, bars provincial civil servants in positions of authority from wearing any explicit symbol of religious belonging. Recognizing that this law contravenes existing Canadian jurisprudence on religious freedom, the Quebec government invoked the notwithstanding clause, a constitutional loophole that prevents judicial review.

The real issue—whether religious expression is an essential right enshrined in law—has been drowned out by a resumption of the “sham fight” between the two solitudes. One of the great Canadian pastimes is a regular reenactment of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in places of power, and here we have it again. Media outlets and policymakers in Alberta and Toronto decry the erosion of religious rights. Politicians and pundits in Quebec, even those who may have had mild reservations about the bill, react by reasserting the province’s right to self-determination; they seize on the remarks of a few zealots to portray English-Canadian concerns about religious rights as the real xenophobia at play.

And so returns, like clockwork, the narrative of “Quebec bashing,” a red herring in which we lose sight of the rights and freedoms of minority groups in Quebec.[2] Let’s be clear: there is no place for attacks on French-heritage Quebeckers as such. Challenges to political choices, as opposed to an inherited identity, are legitimate, however. The trope about “Quebec bashing” too often serves to side skirt genuine, well-meaning questions about policy decisions. It is a powerful rhetorical tool that aims to rally “all true nationalists.” It displaces the debate to grounds were the core issue cannot be resolved. When has going to war with public opinion in the Rest of Canada served Quebec’s interests? How is the debate enriched by giving a platform to the apparent contempt of figures on the other side of the issue?

All of this has, rather, served to conceal more fundamental questions and to ingrain a certain self-satisfaction. If English Canadians and minority groups are up in arms, some seem to think, then the Quebec government must be in the right. This rhetoric detracts from a serious, responsible province-wide discussion about the religious rights of minority groups. It detracts from the legislative precedent set in the area of free expression, religious or otherwise. It detracts from a better understanding of religious minorities, most of which accept the open, pluralistic principles of the society in which they live.

The process of religious disestablishment and secularization from the 1960s onward has enhanced the importance of the French language as the common fabric of Quebec society. It also seems to have persuaded some French-heritage Quebeckers that if they can chase their ancestral religion from all public spaces, they should expect all newcomers—and some minority groups that have been in the province for generations—to similarly conceal all expressions of faith. This view underestimates ordinary citizens’ discernment and ability to understand that a police officer with a turban is not enforcing Sikh religious strictures in his everyday duties, or that a woman who covers her hair with a scarf did not enter the public education system specifically to convert thirty unruly children to Islam. Alas, having emancipated themselves from the most profound connection to the Catholic Church, some citizens now see shackles everywhere.

Ultimately, however Quebeckers decide on this question, the debate should not be driven by recourse to sham fights. It should be driven by a genuine pursuit of equal rights, freedom, and social justice—hardly Anglo-Saxon values. That vision, which would recognize the dignity of minority groups, has slowly and imperfectly grown tangible for Indigenous groups in Canada—with a long way still to go. We may hope that the work of introspection and intercultural dialogue will yield tangible fruits for people who see no conflict between their civic duties, professional responsibilities, and sincere commitment to religious values. Until recently, French Canadians themselves and their expatriated compatriots would have demanded no less.

[1] In their survey of Quebec history, historians Paul-André Linteau, René Durocher, and Jean-Claude Robert state that leaders in both Quebec and Ontario “twisted the meaning of this conflict.”

[2] Although the parallel is imperfect, one would not call criticism of, say, President Trump’s ban on immigration from Muslim countries “America bashing.” Criticism of government policy and injustice is a duty of responsible citizenship.

Leave a Reply