The several million Americans of French or French-Canadian origin, who are among the oldest Americans of European stock, are for the most part human vestiges of the vast continental French empire in North America.

With these words, quoted from historian Mason Wade’s work, Query the Past launched into the story of the transnational French-Canadian community. Four years and 150 posts later, that story remains—in this writer’s view—as riveting as ever.

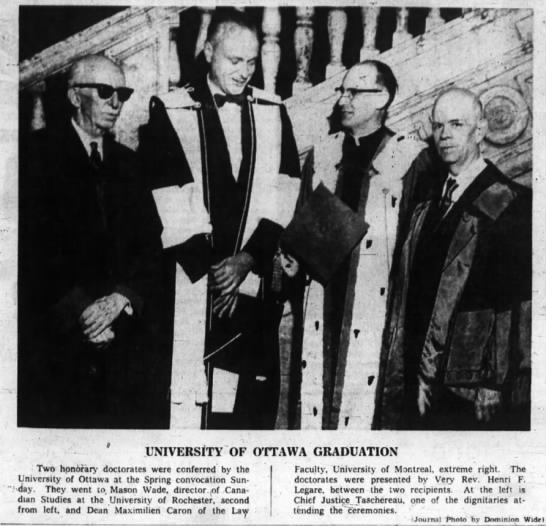

The decision to draw inspiration from Wade was not random. In the 1950s and 1960s, he was one of the leading English-language writers on Quebec history and culture; arguably he was the most appreciated by French Quebeckers, who celebrated his impartial yet sensitive approach. This owed no doubt to his own Catholic upbringing, his intellectual curiosity, the years he spent in Quebec City, and the relationships he forged with French-speaking peers.[1]

One could hardly tell that he was American—and yet the fact that he was mattered quite a bit. Some critics were wont to suggest (then as now, actually) that only French Canadians could properly write French-Canadian history, a view that perhaps reflected frustration about dominant Canadian narratives more than an inflexible stance on who could write what and how. By his own example, Wade proved them wrong and went further. He argued that as an American, he enjoyed a certain detachment that enabled him to steer clear of inherited prejudices and to provide new perspectives and insights. Appropriately, his last work, published posthumously, was subtitled The Perception of an Outsider.[2]

To misquote Lloyd Bentsen, as I regularly do, some people knew Mason Wade; some people worked with Mason Wade. Those people will confirm that I am no Mason Wade. There is, however, a great deal in his journey and career from which to draw inspiration. I have been animated by the same concerns, the same vision, and this blog is a testament to a passion that might well have rivaled his.

This is all to say that from the moment I began studying Franco-American history, in 2012, and from the day I launched this blog, in 2018, a well-blazed trail awaited me. We needn’t even go all the way back to Wade, who passed away thirty-six years ago. In my first substantive post, I mentioned existing blogs as examples. But it wasn’t an option to say, “It’s been done.” As a discipline, history is more than knowledge about the past; it is a field of inquiry. I believed, from my research and publications, that I could inquire further and in novel ways. There was an opportunity to say something different and to nourish a larger conversation. I could bring more French-language sources into that conversation and help raise awareness about a transnational French Canada among English readers. I could bring more academic research into the open. I could bring attention to forgotten stories and scrutinize historical narratives—which involve how we craft the past, how we view it, and what we bring in and leave out.

Well, let it be said, if nothing else, that in these 150 blog posts, there was an attempt.

We have had free snapshots of my paywalled peer-reviewed work. We have had a series of posts on “Those Other Franco-Americans,” which are regularly the most viewed articles on this site.[3] We have had excerpts and overviews of primary and secondary sources. We have had reflections on the state of the field. And yes, the blog has provided me with the irresistible opportunity to opine on contemporary culture and politics.

From the beginning, I have been in distinguished company—company that provides inspiration, especially the young people who take the past seriously. In fact, since 2018, an impressive array of podcasts, projects, and blogs have come into being and it is rewarding to find that each offers something unique and valuable. Even as these endeavors multiply, each—Query the Past included—retains its raison d’être.

Query the Past’s role in this wide-ranging conversation has focused specifically on providing essential historical context. By no means has this been a tough sell. Even if history is too often shrouded in academic jargon—and here I accept some responsibility—most people recognize the importance of studying the past. On its best day, it sheds light on the present, offers perspective, erodes dubious political claims, helps us understand ourselves, and encourages empathy for people who live(d) through very different circumstances. Query the Past represents an attempt to answer each of these contemporary functions of historical study. Here I want to insist on the last two functions.

In the course of these inquiries, which I have sought to conduct with honesty and the greatest possible impartiality, I have meant to advance our understanding of this great, transnational mass of French-Canadian people and its diverse historical experiences. We tend to be products less of certain historical events than of the memory we’ve created about those events. That memory merits our critical scrutiny—and its significance doesn’t erase the importance of understanding the events themselves (wie es eigentlich gewesen, for the history graduates who read this).

Perhaps because my work has been so closely aligned with a specific ethnic community, some people have at times misunderstood my goals and thought that my work was to serve the community. Admittedly, for all of their claims to neutrality, historians cling to their right to social engagement and to moral values as individuals and citizens. I am no different. But my work on Franco-Americans is history, not heritage.[4] It means defying absurd claims to absolute truth and singular visions of the past that are presented as definitively correct. It also means offering historical understandings that sometimes clash with a community’s sense of itself and of its past.

It’s important to show that we value honest inquiry and that we can work together towards an ever-better approximation of the truth, historical or otherwise. We can also be more ambitious in the payoffs we envision from the work of disaggregating myths and memory. It may be that we can foster greater intercultural understanding and dialogue across the international border and across other, less tangible boundaries. We might stand for the dignity and rights of minority groups, whoever and wherever they may be; we might defy the nationalistic narratives that too often turn specifically against these minorities. We might look with suspicion upon cultural insularity.

This vision may explain the regular recurrence, here, of the otherwise obscure Prosper Bender, a nineteenth- and twentieth-century intercultural broker to whom I’ve felt special kinship. (Not least because I too am a fake doctor.) Bender helped acquaint Anglo-Canadians and Americans with le fait français en Amérique without ever sharing either side’s canonical prejudices. In fact, there’s reason to think that Bender felt uncomfortable in both cultural milieus. Having a foot in each culture often means being at home in neither. It means feeling perpetually unmoored, adrift between communities. Perhaps that’s why Bender broke with the noisy soirées of Ding-a-Long Street, in Quebec City, and planted himself in Boston. And perhaps that’s why I—following Bender’s flight to New England—have felt particular affection for Franco-Americans, who for generations labored through their own cultural discomfort.

Though Mason Wade went north, whereas Bender found a new arena in the United States, both were engaged in the heady work of tracing French Canadians’ place in North America. Both promoted intercultural understanding—and, in a cruel twist, both are now largely forgotten. The reason isn’t hard to find. In the long term, their views did not play well on either side of the cultural divide. Their efforts did not mesh well with the still-prevalent nationalistic narratives. They were men of strong opinions, but not in ways that served political agendas.

I note this not to place my body of work alongside theirs; quite the opposite. The fate of our work is always in doubt and we should approach our accomplishments with humility, knowing their longevity to be continually in doubt. Even through this milestone moment, then, Query the Past is best regarded as the seed to something else—hopefully, as a blog that has nourished bigger and better history and fostered an appreciation for the struggles of those who have come before and those now in our midst.

Therefore, knowing that nothing is final, but that knowledge is worth pursuing and some values are worth upholding, again and again, let us attempt.

[1] One short biography alludes to the Franco-Americans in the vicinity of the family’s country home in Cornish, New Hampshire—an exotic presence that would have elicited Wade’s curiosity.

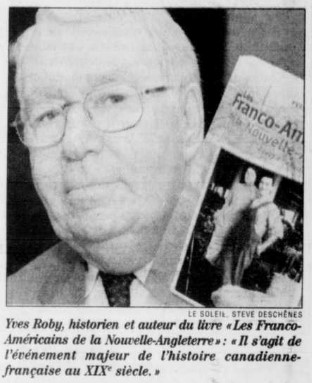

[2] Wade left an impressive legacy through his published work and his stint as president of the Canadian Historical Association. He was also the keystone of a nearly unmatched academic lineage. Yves Roby, often described as the greatest historian of Franco-America, spent a year in Wade’s demanding seminars in Rochester, New York; his work focused on American history and Canada–U.S. relations, but it is precisely in Rochester, under Wade, that he began to take interest in “Francos.” Roby in turn influenced and inspired several generations of scholars of Franco-American history. He was a supervisor of Martin Pâquet’s M.A. thesis and Yves Frenette’s Ph.D. dissertation in back-to-back years.

[3] This points to the demand for alternative local stories from lesser-known Franco communities.

[4] The blog might at times further the reinvigoration of Franco-American culture because of its focus, but such was not its primary purpose, not least because that work belongs to Franco-Americans.

Leave a Reply