Last year, on Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, the Montreal-based La Presse offered us a fascinating article about the Québecs—yes, plural. Reporter Jean-Christophe Laurence was not using the term metaphorically to describe the different regions or cultures that make up the province of Quebec. He was writing about the Québec family, for, yes, “Québec” happens to be a province, a city, and a last name.

Laurence explained that one was more likely to find Quebecs in the Philippines than in the province of Quebec where, according to his research, there are none. But, for a brief time, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the St. Lawrence River valley and the Eastern Townships had their Québec family.

My curiosity was sparked when I came across an Emélie Paquet dit Québec in my genealogical research. Her grandson married Louise Lacroix (1876-1960) in Knowlton at the end of the nineteenth century. How did this Emélie relate, if at all, to the Québecs in the article from La Presse? And where have they all gone?

Only genetic genealogy is likely to solve the mystery of Emélie’s biological parentage. The record of her 1824 wedding to Louis Giroux dit Jolicoeur does not name her parents explicitly, but mentions the presence of one Augustin Québec, her adoptive father. The wedding occurred in Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir (now Marieville), where Augustin Paquet dit Lavallée and his wife Charlotte Ménard resided. The relationship between this specific Augustin and Emélie is largely cemented by the baptism of the latter’s first child—also in Sainte-Marie, also in 1824. The child’s godmother was Charlotte Ménard; Emélie and her husband Louis would thus have followed a common practice of naming one or two grandparents as godparents of their first child.

In Augustin’s own wedding record, from 1812, he appears as a Paquet dit Lavallée—with no sign of an additional surname or alias. It bears noting that the “old” province of Quebec had disappeared with the creation of Lower Canada in 1792. For much of the nineteenth century, “Quebec” referred simply to the city of that name. A geographical connection may explain the emergence of a new surname: Augustin’s father, François, had come to the southern part of the colony from l’Isle d’Orléans, near Quebec City. He may have adopted “Quebec” so as to distinguish himself from other Paquets or Lavallées in his adoptive community.

It is, however, unclear at the moment whether François used the alias at all. Augustin may well have been the first Québec. Could this have been a nom-de-guerre earned during the War of 1812? Uncertainty remains. Still, the name had such significance as to stick and as to be passed down to Augustin’s children, starting at least with Emélie.

We next find family members in the Eastern Townships in the 1830s. Following the Roys and the Bombardiers, they were at the leading edge of French-Canadian settlement in Missisquoi County. In 1839, Emélie (listed as “Paquet”) and her husband traveled to Sainte-Marie to have a child baptized. The priest gave their place of residence as Dunham Township. The same year, one of her brothers through adoption, Joseph, married Marie Bérard. This act appears in the Saint-Chrysostôme parish records, but the priest was a Father Dallaire who traveled to the Townships as a missionary prior to the establishment of parishes. It is likely that he celebrated the wedding in Dunham, where the Paquet dit Lavallée family lived, or in Saint-Armand, home of the Bérards.

Emélie’s last name and alias disappeared with her, her husband’s name being passed on as per tradition. It is unclear whether her non-biological brother, Joseph Paquet dit Lavallée, ever used “Québec.” But two other siblings did—and thus comes a fascinating cultural twist.

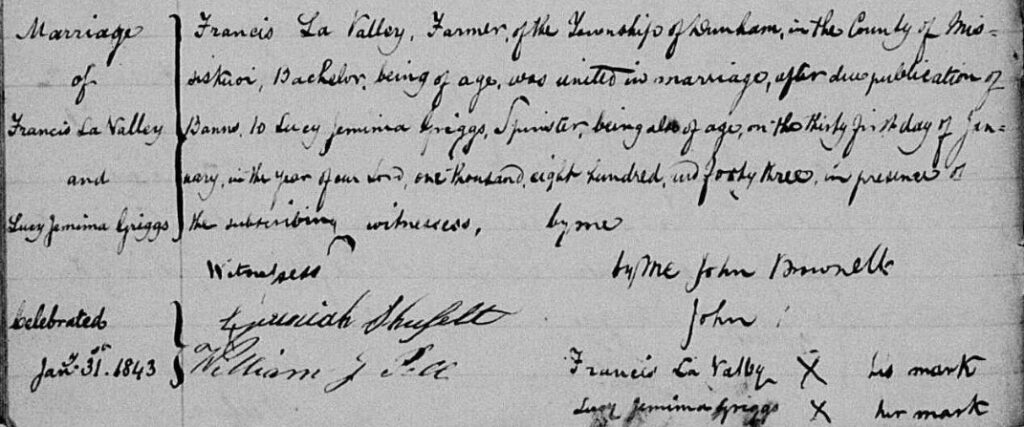

Augustin and Charlotte were also the parents of François and Maurice, born respectively in 1819 and in 1825. Both were christened in Sainte-Marie. They accompanied their parents to Dunham, where, as young men, they found spouses. François or Frank married Lucy Jemima Griggs, the daughter of Abraham and Sarah Griggs, at the Methodist church in Dunham in 1843. Lucy’s Protestant baptism, celebrated several years earlier, confirms her parents. Further, Maurice or Morris married Priscilla Griggs, whose marriage record has yet to be found. But the couple lived next to Abraham and Sarah Griggs, which, in addition to the concordance of ages, suggests that Priscilla was their daughter.

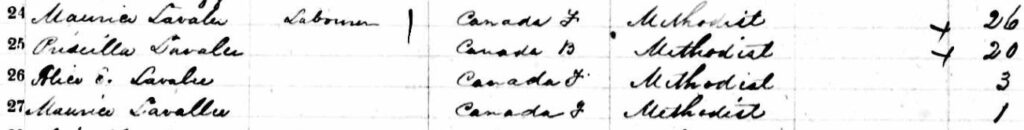

Two brothers married two sisters and thus the Paquet dit Lavallée clan, already surrounded by English-speaking Protestants, integrated that “foreign” world. Frank and Morris appear in census records as Methodists and there seems to be little doubt that their children were raised first and foremost in English, their maternal tongue. Most bore English names.

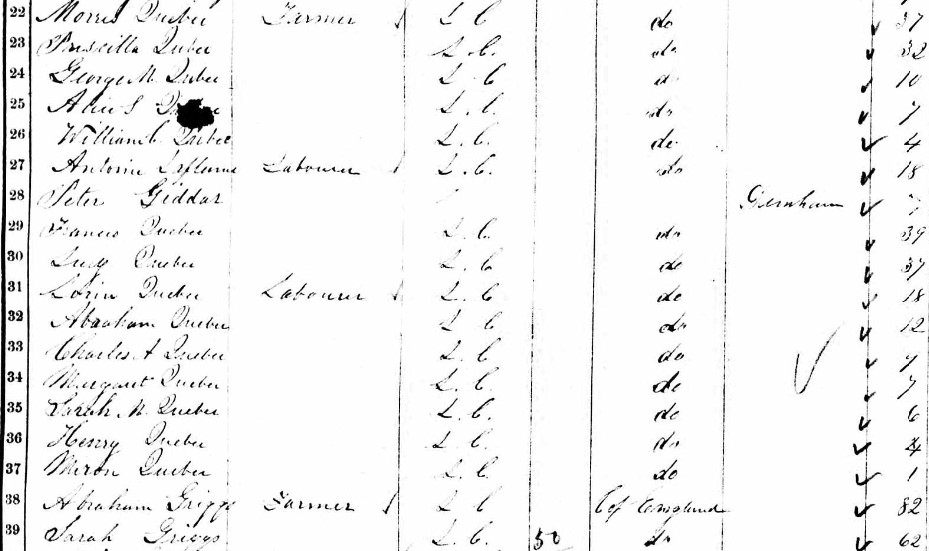

But what of the unusual alias? “Lavallee” is the name under which these two young households appear in the census of 1851 (conducted for the most part in 1852). A decade later, we find, all on the same census page, Abraham and Sarah Griggs and… the households of Morris Quebec and Francis Quebec.

The reassertion of this last name in official records was gradual and inconsistent. A contract with former legislator Seneca Paige dating to 1855 gives Morris’s last name as “Quebec.” Nearly twenty years later, in a transaction involving yet another politician, George Barnard Barker, a francophone notary gave his name as “Maurice Lavallée alias Quebec.” For his part, his brother appears in an 1864 record as “François Paquet alias Lavallée.” In short, we are confronted with a tangle of monikers that dwarfs whatever concern may have emerged, in recent decades, about the rise of hyphenated last names. The inconsistent usage over the course of decades negates the idea that “Quebec” asserted itself as these French Canadians moved to a predominantly English environment. They were far from the sole Canadiens in the region and, in any event, “Lovely” and “Valley” (as some Lavallées became) would have been equally serviceable and English-friendly surnames.

But where have all the Quebecs gone? We should recall that both French and English Canadians left their native land in droves in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was especially true in specific borderland regions. As historian Jack Little has argued, the Eastern Townships were long an extension of the Vermont frontier. The counties of Stanstead, Brome, and Missisquoi were closely integrated—economically, culturally, and demographically—with their counterparts in Vermont. For English speakers, including the Griggs and the next generation of Quebecs, the international border was even more of an imaginary line than it was for the Canadiens.

So it was that many Quebecs spied better opportunities over the line and went to Vermont, Massachusetts, and beyond. Morris’s widow, Priscilla, died in Barton, Vermont, about eighteen miles from the border. Their daughter Alice had married in Richford in 1878. One child, Edward, went to Ontario, where he married a McCauley in 1890. A son, William, married in Newton, Massachusetts, in 1897. The marriage records for these siblings give “Quebec” or “Quebeck” as the spelling. George, another sibling, who had married a Catholic, Marie Goyette, in Dunham, migrated to Massachusetts in 1892. They were living in Lowell in 1910. George died several years later.[1] Carolyn, also a child of Morris and Priscilla, died in Exeter, New Hampshire, in 1943.

Jesse Quebec also merits mention. A shoemaker, Jesse lived in Brome and Dunham townships in the 1850s and 1860s. He married Charlotte Pickle or Pickel. His age, his last name, and his place of residence would suggest that he was a child of Augustin Québec and Charlotte Ménard and thus a brother to Frank and Morris. He may even have been the Augustin Jr. baptized in Sainte-Marie in 1823. He appears unequivocally as Quebec in notarial records. In 1866, Jesse and his family crossed the border and settled in New York State. They were in Black Brook in 1880 and in the Town of Franklin several decades later.

To put is simply, like the province, the Quebecs had their own “great hemorrhage.” In three or four generations, they went from l’Isle d’Orléans to the United States. They followed one another into a foreign but still familiar land. There is irony in Quebecs leaving the land with which they should have been so closely identified—to the point of total disappearance. But their experiences reveal in some small way the extent of expatriation in a critical era of Quebec history.

La Presse followed up its story on Quebecs with small corrections and a look at the surname “Canada”; it is available here.

[1] George was simply a Lavallée at the time of his wedding, but the baptism of one of his children, recorded in Sweetsburg in 1880, identifies him as “George Maurice Lavallée Québec.”

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Love the phrase ” the international border was even more of an imaginary line than it was for the Canadiens.” Though the most recent Canadian born are my great grandparents, I still imbibed the sense that New England and Quebec and the provinces to the east were the same country. Still feel a slight irritation at the existence of border-crossings. (:

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - June 22, 2024 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte