See Part I here.

Six years after the invasion of St. Albans by Confederate agents, a different spectacle played out in the town center, though this one, too, was the doing of people who had descended from Canada:

At 11 o’clock in the forenoon the Convention formed in procession, under escort of the St. John Baptist Society of this place, and, led by the St. Albans Brigade Band, marched through the principal streets, bearing the colors of the United States and of France, besides the flags of their organization…

The day was August 30, 1870, and Charles Moussette received this procession at St. Albans’s Academy Hall. Thus opened the annual convention of French Canadians in the United States.[1]

Though more modest than subsequent conventions, this was no small affair. It drew delegates from communities as far apart as Detroit, Michigan, and Biddeford, Maine. From Quebec came Charles Thibault, who was beginning to make a name for himself as a Conservative activist and public speaker—he was then already an exponent of the providential mission of French-Canadian emigrants. Also present was Michel-Adrien Bessette, member of the provincial assembly for the riding of Shefford, who had married many years earlier in nearby Highgate, Vermont. A Catholic priest from Coaticook, in the Eastern Townships, also visited the convention; he had a special interest—and a special mission—as a colonization agent for the provincial government.[2]

The convention did not make much of a splash in the Quebec press. The on-going war between France and Prussia was of far greater interest to editors and readers. But the St. Albans gathering did reverberate in a noticeable way in the pages of La Minerve, in Quebec City.

In September 1870, La Minerve printed convention reports from an unnamed correspondent, their likeliest author being Charles Thibault. This person denounced the presence of Arthur Buies in St. Albans. The editor of the irreverent, liberal, and occasionally anticlerical Lanterne, Buies attended the convention simply from personal interest. In the press, he and the Minerve correspondent would disagree on whether he was invited to speak at the August 31 banquet, which said something of the religious and political discourse that was or could be held in nascent Franco-American organizations.

At the request of New York delegates, Buies served as the recording clerk for an afternoon session. When he returned later that day for the banquet, pastor Zéphirin Druon—from a makeshift pulpit, apparently as master of ceremonies—prevented him from addressing the delegates. First, Druon called Edouard Lacroix of Detroit when some in the audience asked the Lanterne editor to speak. Then, Druon went a step further and announced to the members that this was the man behind the scurrilous attacks on the bishop of Montreal.[3] As it was getting late, the pastor called delegates to leave with him such as to adjourn for the day. Many did. Buies was kept from delivering a proper address. As Quebec’s divergent ideological visions disembarked in St. Albans in the persons of Thibault and Buies, truly French Canada was transplanted in the United States. Of course, if willing to make small, political concessions to the Great Republic, cultural and religious elites in French Vermont and French New England would overwhelmingly follow the vision laid out by Thibault and Druon.

St. Albans’s time as a centre de rayonnement of French-Canadian culture in the United States came to a close in the years following the convention. Almost exactly a year after that event, fire destroyed the offices of Le Protecteur canadien. Antoine Moussette had already sold his share in the paper to become a backer of Ferdinand Gagnon’s first journalistic effort in Worcester, L’Etendard national. After the fire, Druon, now sole proprietor, sold the list of Protecteur subscribers to Montreal businessman Georges Desbarats, who owned Gagnon’s paper. Gagnon, later deemed the “father of the Franco-American press,” was thus doubly the heir of early efforts in St. Albans.

Soon after the demise of the Protecteur, Moussette and Frédéric Houde created L’Avenir national in St. Albans; they sold it either the next year or in 1873. Towards the end it had an impressive 3,500 subscribers and was circulated in the western states. In 1873, Gagnon and Houde joined forces to establish Le Foyer canadien. Houde moved the paper to St. Albans—the third French periodical in the city in five years—while Gagnon sold his share and established the long-lived Travailleur that made his fame. The Foyer ceased publication in 1875. Still, that an editor would move a French-language newspaper from central Massachusetts to northern Vermont is very telling of the French fact in this era—not to mention the contemporary stature of a city that would be eclipsed by new patterns of migration.

The legacy of French-Canadian community organization in St. Albans also lived in the most illustrious Franco-American of the late nineteenth century. The anglicized Civil War veteran Edmond Mallet was allegedly inspired to renew with his heritage when picking up an issue of Druon’s Protecteur; according to Alexandre Belisle, the paper “converted” Mallet to the cause of Franco-American survivance.

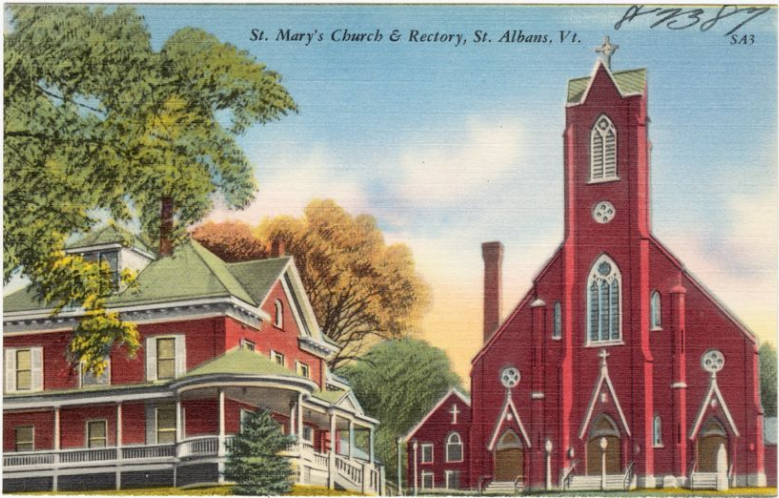

French Vermont culture did not disappear or become irrelevant. A grand celebration of St. John’s Day involving Canadian delegations occurred in 1875. The French community had earned, by virtue of its numbers, its own religious space in 1871; a proper French Church, Holy Angels, was built in the 1880s. Around the same time, a circle of the Dames de Sainte-Anne was established.[4] That spirit of organization carried into politics: in 1892, the French-Canadian Republican club of St. Albans welcomed future president William McKinley.

We cannot argue that the winds of nativism never blew through the area, but this was a tight-knit community where economic interests facilitated a sense of common cause. Well into the twentieth century, French Canadians formed an important share of the railway labor force. An influx of farmers Quebec helped to revitalize the countryside following the Great War. French-owned shops were prevalent along Lake Street, in the vicinity of Holy Angels Church, but it was not unusual for business owners on Main Street to hire French-speaking clerks. Certain derogatory terms seem to have arisen at least as much from class prejudice as from ethnic feeling.

French was heard on the streets of St. Albans and the convent school still offered some of the core subjects dans la langue de Molière (or Crémazie) following the Second World War.[5] In fact, some eighty years after the great French-Canadian national convention it had hosted, the French-Canadian community in St. Albans continued to thrive. When the local council (no. 37) of the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste reached its fiftieth anniversary, in June 1951, it earned widespread kudos and the local English newspaper, the Messenger, published a special issue to mark the occasion. A grand parade passed through the city on June 24 in the presence of Montreal mayor Camilien Houde and the bishop of Burlington, Edward Ryan. Adult membership in this USJB council—over 600 people—was then at an all-time high.[6]

Franklin County continues to have one of the highest rates of French-Canadian ancestry in New England. In 1990, among Vermont communities, the town of Norton, further east in Essex County had the highest proportion of people of French-Canadian descent. But places like Swanton and the City of St. Albans were not far behind—and were in fact ahead of Winooski. A sense of connection to this immigrant and ethnic past was still visible in 2000, when a full quarter of respondents in Vermont claimed their first ancestry as French or French-Canadian. In the decade that followed, St. Albans hosted a French-Canadian Heritage Festival. People who grew up in the region—artist Michèle Choinière, for instance—still tell the story of ethnic Vermont and Franco-America.

Today the culture survives not in the narrow ideological sense anticipated by Father Druon, nor perhaps in the language, but in customs and connections that invite wider participation and interest—something more eclectic, more inclusive.

Do you have a French Vermont story you would like to share? Comment below or on social media!

[1] Though some family relation between Antoine and Charles Moussette is likely, I have yet to determine with certainty what it was.

[2] Still, repatriation does not seem to have held the same significance that it would in later conventions’ debates.

[3] The local société Saint-Jean-Baptiste had welcomed Bishop Ignace Bourget while he traveled to New York City a year and a half earlier.

[4] In the early years of Druon’s tenure in St. Albans, the local education committee agreed to rent out the Catholic church’s basement as a temporary classroom for public school children, relieving pressure on overcrowded tax-funded schoolhouses. Druon seems to have been widely respected in the community; he had earned similar esteem as a leading religious figure in Civil War-era Montpelier.

[5] Vermont was spared English-language education laws that marked many other northeastern states in the 1910s and 1920s. Here, French Canadians, the largest foreign-language minority group in the state, found numerous Anglo-Saxon allies. S. N. Griscoll of St. Albans stated before the House Committee on Education that “French Canadian families are putting the abandoned farms of northern Vermont on the map and we should not discourage them by not allowing the teaching of the French language in the schools.”

[6] St. Albans’s French heritage was again on display when the city celebrated its bicentennial in August 1963. On this occasion, Quebec premier Jean Lesage sent Guy Lechasseur, a member of the legislative assembly, as his official representative.

Sources

Beyond the sources linked in the text, Alexandre Belisle devotes a full chapter to the Protecteur in his history of the Franco-American press. Edouard Hamon’s work on religious organization and a local online history of Holy Angels are very brief; more extensive newspaper and archival research would be needed for a fuller story of the parish. Digitized newspapers on the Library of Congress website, Newspapers.com, and the Collection patrimoniale of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec hold an overwhelming amount of information on St. Albans down to the 1960s. La Minerve, available in digital form on the BAnQ website, covered the national convention in early September 1870. I accessed census records on Ancestry.com.

For more on French Vermont, check out episodes of Brave Little State (VPR) and Northwest Passages (produced by the Saint Albans Museum).

Ironically, many of the dyed-in-the-wool Yankees that held French-Canadians in contempt were themselves of French background, being descended from Huguenots. In fact, the town of Barre was named after French Huguenot descendant Isaac Barré. Surnames like Revere, Bowdoin, Faneuil, Duval, Durel, Mullins, Beaumont, Duryea, Biney, Manviel, Girard were all French. What divided them was religion, the latter being avid anti-popists.

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree