One particular claim to fame dominates the history of St. Albans, Vermont: the Confederate raid on local banks that was staged from Canadian soil in 1864. Other events that truly made the city remain little known to outsiders, as is the history of the region as a whole.

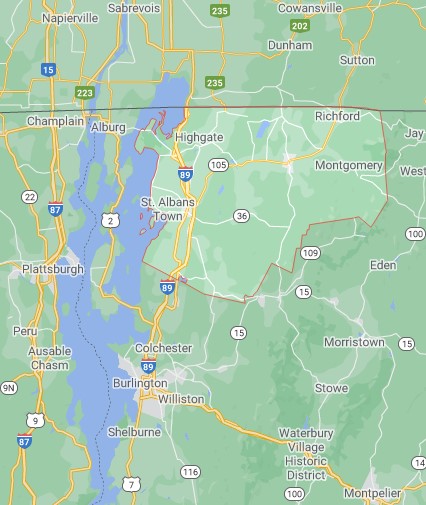

The Confederate raid at least has the virtue of reminding us that St. Albans is a stone’s throw from the international border and that Canada played no small role in the making of northern Vermont. That area welcomed Canadian political dissidents in the late 1830s; the Irish nationalists known as the Fenians had their turn and launched ill-fated attacks into Canada in 1866 and 1870. In the meantime, St. Albans grew as a rail hub thanks to its northern connections. Additionally, in the nineteenth century, the whole of Franklin County, which is adjacent to the border, bore the heavy imprint of permanent French-Canadian settlement and community life.[1]

Vermont often stands in the shadows of Franco-American history—as though the Franco history that matters happened elsewhere. And when discussions of French Vermont life do occur, they seldom stray from Burlington and Winooski.[2] French-Canadian migrants to the Green Mountain State did not form giant urban communities as we see in other parts of the Northeast. No less, though they do not fit that pattern, even in this remote corner of New England their historical significance is indisputable and perhaps larger than it was in the large manufacturing cities.

Let’s consider this. By 1850, the Canadian-born amounted to 13.5 percent of all residents of Franklin County. Even while accounting for possible English Canadians, this was no small number. In Burlington, whose population now exceeded 7,500, the ratio was about the same. In 1860, Canadian-born individuals and children born in the United States to Canadian parents represented a full quarter of the population of St. Albans; the same was then true of the city’s more rural neighbor, Swanton. One out of every four locals that the Confederate raiders met in their eventful outing in St. Albans would likely have been a French-speaking Canadian.[3] But these migrants’ visibility in census records is not mirrored in contemporary newspapers, such that this set of back-page Americans is often relegated to obscurity.

Historiographical obscurity of this kind has not led merely to a geographical problem in the telling of the Franco-American past. It is easy to forget—in light of existing literature—that emigration from the St. Lawrence River valley to the U.S. Northeast did not begin in the 1860s.

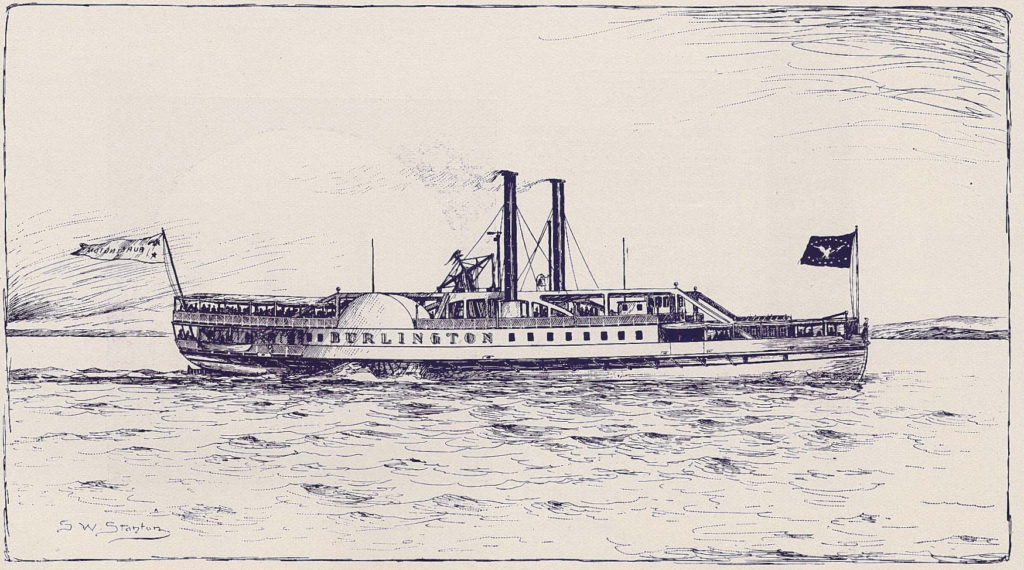

In August 1840, La Canadienne ran a report on the French Canadians of Burlington. These expatriates were not Patriote sympathizers who, after rising up against British power in 1837-1838, had fled south. The newspaper stated that there were 300 French-Canadian families then living in the city. A large proportion hailed from Yamaska, a parish on the lower part of the river of the same name. The corner of Burlington where they congregated became “New Maska.” Proximity to la patrie and ease of travel counted for something in this migration: steamboats had been plying Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River for decades at that point.

St. Albans benefitted from those steamboat connections. In 1853, a newspaper advertised an excursion from Quebec City to St. Albans, likely utilizing the same alternating lines of rail and waterwheel that Henry David Thoreau had taken several years earlier. But the small city was then already well-known to French-Canadian families with one foot on each side of the border.

Opportunities for young men seeking to found a household of their own were then quite narrow, along the St. Lawrence. The lumber industry, which had offered seasonal wages for decades, was entering a decided slump. Due to rapid population growth, access to arable land was increasingly difficult—as was work for day laborers. As for those living from agriculture, increased competition from the Midwest and the integration of the North American market entailed structural changes. According to some historians—Bruno Ramirez, for instance—those changes cleaved Canada’s farming class into “haves” and “have-nots.” The latter would have to seek work abroad.

The irony is that Vermont was facing those same pressures, at mid-century. Farmers turned to dairying roughly at the same time as their counterparts north of the border. Young Vermonters, instead of trying to beat Midwesterners, decided to join them. But the situation was not nearly as dire as in Quebec, whose crisis owed to population perhaps more than anything else. Opportunities opened up in Vermont. People came and it is these migrants—predominantly Irish and French-Canadian—that prevented Vermont’s population from declining in the second half of the nineteenth century. That they came to form a quarter of the population of communities like St. Albans and Swanton hints indeed at their economic and social significance.

The period of organized social and cultural life among French Canadians in Vermont began in Burlington in 1850, with the establishment of the first French national parish in the United States.[4] At this point, St. Albans and other communities tend to fall back into the shadows. But immigrants in these places were neither inactive nor, at the time, invisible. In 1866, the French Canadians of St. Albans formed a new société nationale and elected grocer Antoine Moussette as their president. Moussette served as president of the convention held in Troy, New York, the following year; he would return to Canada at the end of the 1870s.

Plans were quickly made to establish a French-language newspaper in the city. Those efforts came to fruition in the spring of 1868 with the publication of Le Protecteur canadien. The paper’s co-owners and editors were Moussette and Zéphirin Druon. Druon was a French-born priest and a member of Bishop Louis DeGoesbriand’s diocesan council; after a pastoral stint in Montpelier, he spent twenty-five years in St. Albans.

Until Winooski asserted itself as a major manufacturing city, powered in great part by French-Canadian labor, St. Albans could reasonably claim to be the Franco capital of Vermont—or at least a major center that rivaled Burlington in influence. That became particularly clear when, in the summer of 1870, it hosted a grand convention of Franco-Americans from other parts of the state and beyond. Long before these immigrants and their children gathered in Nashua and other, better-known cities, St. Albans had its day in the sun and welcomed delegates from all across the Northeast.[5]

See Part II here.

To add to last week’s listing of exciting Franco endeavors, we should add the Unnamed Narrative video series by Matt Pelletier (or shall I say, “Matt Pelletier”), whose first capsule is now available. Further, I highly recommend Timothy St. Pierre’s thoughtful and powerful “Acknowledging and Confronting Racism in Franco Communities” in the latest issue of Le Forum.

For more on French Vermont, see my post on Francos in Barre.

[1] This post on St. Albans was brought to you by the good people of Twitter who voted in a poll I posted on April 4. Of potential “other” Franco communities I might write about, the St. Albans area received nine votes, with Malone, New York, the runner-up with six. Poor Rumford, Maine, and Newmarket, New Hampshire, received four and two votes respectively.

[2] In the small group of scholars who have studied French Vermonters outside of Burlington and Winooski are Mildred Huntley, Ralph Vicero, Peter Woolfson, and J.-André Sénécal.

[3] These figures come from my own systematic sampling of census returns from 1850 and 1860. In the case of the latter, I seize a full third of available data as part of that sampling.

[4] The need for distinct religious institutions for French-Canadians in St. Albans was clear as early as 1847, when an observer informed the bishop of Boston that a francophone Protestant minister was making converts in the area. According to Alexandre Belisle, the first French-Canadian “national” society in the United States was St. Albans’s société Jacques-Cartier, founded in 1848.

[5] The previous convention of French Canadians in the United States had been held in Detroit in October 1869. Antoine Moussette had attended.

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - November 14, 2020 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree