This week we resume and conclude our overview of New Bedford’s Franco-American history. See Part I here.

Franco-Americans’ institutional network continued to grow in the 1890s and early 1900s. The Francs-Tireurs, one of the earliest and largest fraternal and cultural societies in New Bedford, played a significant role in community building. Other groups appeared in quick succession. The Zouaves, the Union ouvrière, and the local société Saint-Jean-Baptiste merged in 1903 to become the Fédération franco-américaine. Other associations included the Franco-American Chamber of Commerce, a council of the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste, and the Forestiers. A visit of Alphonse Desjardins, the father of Quebec’s caisses populaires, inspired the creation of a similar credit union in New Bedford in 1911. Councils of the Association Canado-Américaine emerged in the 1920s and 1930s. Remarkably, by 1931, four of the eleven officers of the ACA’s Cour Saint-Rosaire were women. At the Cour Sainte-Anne, at that time, women formed the majority of the board.

This rich institutional network was reflected in the press. For a time, in the early twentieth century, New Bedford was the only city with two daily French-language newspapers. The Journal was a local edition of Fall River’s L’Indépendant. For its part, L’Echo began as an appendix to La Presse, published in Montreal. Its creator, J. B. Archambeault, had grown up in Nashua, studied in Saint-Hyacinthe, and served in the New Hampshire legislature. Editor Amédée Lacasse had likewise studied in Quebec and lived for a time in New Hampshire. Both men exemplified the middle-class circuits between mill cities.

The Acadian Community

On Labor Day weekend, 1923, hundreds of French-speaking delegates poured in from other New England centers for a two-day cultural event. These were not French Canadians in the strictest sense, however. New Bedford boasted an Acadian community that rivaled those of Fitchburg, Lynn, and Waltham, and it was these residents who had the honor of welcoming confrères from across the region.

By then, Acadians, perhaps initially drawn to New Bedford by opportunities in the fisheries, were well-established in the city. They had sent delegates to the convention of the Société l’Assomption in Waltham in 1902 and hosted the Mutuelle l’Assomption in 1906. A new burst of immigration occurred shortly after the First World War; according to Clarence d’Entremont, these migrants came from eastern New Brunswick near the Northumberland Strait in particular.

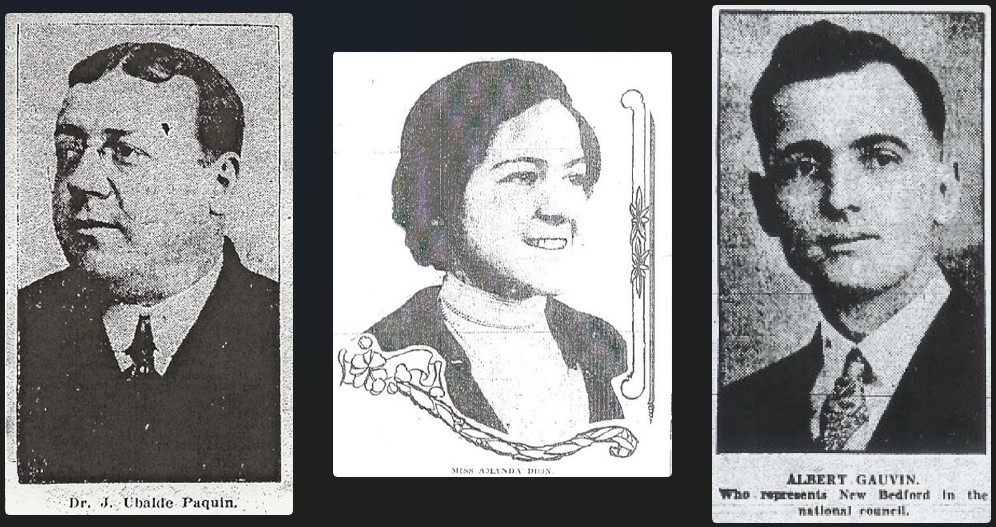

The 1923 event was a convention of the U.S. Société l’Assomption, with members of its supreme council coming from the major industrial centers of the state. St. Anthony’s church served as headquarters; the highlight was undoubtedly the automobile rally to Fort Phoenix for a clambake. “In this city,” the local paper reported, “[Acadians] number about 3000 people, some six hundred families, New Bedford being considered the largest Acadian centre in the United States. For the most part, they live at the north end and are communicants of St. Anthony’s and St. Joseph’s parishes. It is claimed that there are close to 100,000 Acadians scattered all over this country, their immigration covering a period of some sixty years.” There were still two Acadian societies—headed by men with names likes Poirier, Arsenault, Richard, and Hébert—in New Bedford in 1933. But the process of melting into a much bigger French-Canadian stew had begun.

Prominent Figures

A burgeoning middle class provided leadership in all of these cultural endeavors. One prominent example is Louis Z. Normandin, a trusted obstetrician who had helped deliver an estimated 7,500 babies by 1914. A founder of the Zouaves, Normandin served many years on the local board of health and, throughout his tenure, was the only physician on the board. He also played a role on the local school committee and became an alderman. That he straddled the cultural and civic realms was made plain by his membership in Franco-American societies and in the Elks. During the First World War, Normandin maintained that French Canadians had the duty to support Great Britain. His death in 1924 was front-page news in the Evening Standard; he had earned the title of father of New Bedford Canadians. Among the other medical professionals in the city was Governor Aram Pothier’s younger brother Joseph-Charles.

We should also mention Louis G. Destremps, a native of Berthierville, Quebec, who settled in the city in 1905. An architect, he designed a number of New Bedford buildings, including the Third District Court. He was similarly a member of the Elks and the Francs-Tireurs.

The Granby-born Asa Auger served his community as an attorney and his two sons, both of whom attended Dartmouth, followed in his footsteps. The youngest even went to Harvard. Several attorneys sought political office. Republican J.-A. Gauthier, a native of Berthierville, articled under Hugo Dubuque and became the first Franco-American to represent the district in the legislature.

New Bedford-born Oscar U. Dionne also received education on both sides of the border. He served several terms in the state legislature and was named U.S. attorney for Massachusetts in 1928. He appeared on the Republican ticket as candidate for the state treasurer’s office in 1934. In fact, that very year, the Franco-American Civic League met in New Bedford and welcomed nearly all of the Republicans running for statewide office. Appearing alongside Dionne, gubernatorial candidate Gaspar Bacon addressed the assembled voters in French. Both of them would be defeated that November.

Political interest and involvement among New Bedford Franco-Americans had also been apparent when the Jackson Bill for English-only public instruction was proposed in 1919 and when women were granted the right to vote. Despite earlier reservations in the community about female suffrage, once the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, Asa Auger, then president of the Chamber of Commerce, and Dr. J.-Ubalde Paquin worked to have Franco-American women registered. Even a local priest invited women to take interest in politics and public affairs. Paquin declared, “Si nous avons réussi dans le champ économique, religieux et national, nous ne le devons pas aux hommes, nous le devons aux mères. Et, c’est ici qu’il me ferait plaisir de chanter: ‘Vive la Canadienne!’” There’s ample reason to believe that such enthusiasm stemmed from a desire to maintain Franco-Americans’ overarching influence at the polls.

Deindustrialization

Franco-Americans helped drive New Bedford’s economy, constituted a large percentage of the population, exerted political influence, and became visible through their social and cultural celebrations. Yet the city and its biggest ethnic community are both relegated to the margins of the larger regional narrative. Part of the reason lies in other cities’ comparative advantages. Unlike Woonsocket, New Bedford never had a majority-French population. It didn’t produce industrial and literary icons like Lowell’s mill girls and Jack Kerouac. At no point was it the biggest Franco center in its state, which Lewiston and Fall River were. Nor was it home to a large, influential regional organization—and here we might think of the Manchester-based Association Canado-Américaine (ACA).

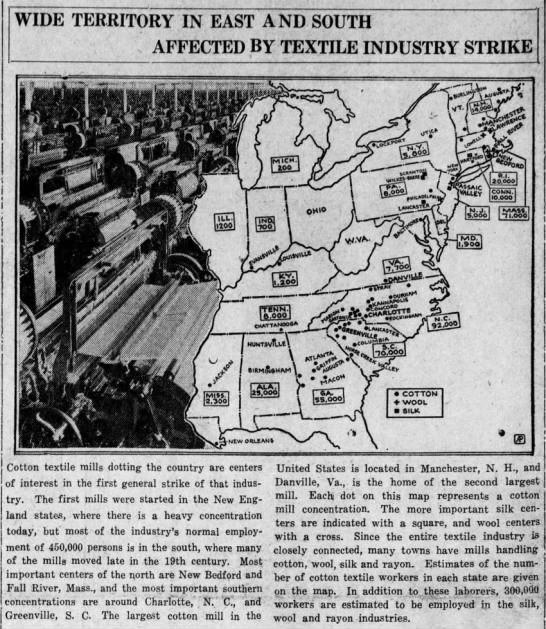

We might also posit that New Bedford’s Franco-Americans faded from view due to the fate of the local economy. As early as 1901, testimony before a congressional committee highlighted the competition posed to New England industry by the Southern states. The New South ideology produced substantial gains, with some mills being established by New England companies and others being the creation of local Southern interests. There, corporations benefited from immediate access to cotton, the power provided by Southern coal, and even cheaper labor. New Bedford’s record of industrial innovation could only do so much against outside competition of this kind. Further, in the chase for elusive profits, factories increased output, which lowered prices and sparked a crisis of overproduction. (Labor activists in New England were also quick to blame the policies of the Republican Coolidge Administration.)

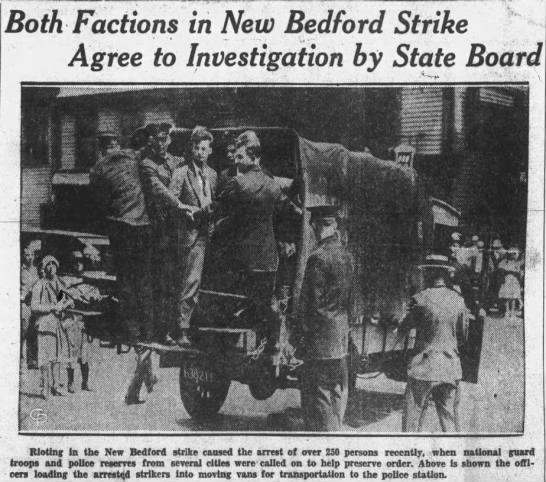

Northern factories had to resort to wage cuts to remain profitable. This was one of the justifications for a ten-percent cut that New Bedford mills sought to introduce in 1928. Workers—Franco-Americans included—responded by striking. The length of the strike (April to October) attests to the local working class’s commitment to the cause; it may have sensed that a definitive stand was needed to protect its own economic security. Tensions rose during the summer when hundreds of picketers—men and women—were arrested. Workers became impoverished and leftist organizations with socialist tendencies posed a challenge to both mill owners and the older textile labor union. Finally, the main parties compromised and settled for a five-percent wage cut. Of course, only a year later, the stock market crashed and announced continued lean times in New Bedford and beyond. Tellingly, whereas the city’s population had nearly doubled from 1900 to 1920, every census from 1930 to 1980 marked a decline in residents from the prior enumeration.

The Great Depression altered the physical landscape of the city because of the hardship it caused, but even more so because of opportunities created by the federal government. The Works Progress Administration provided jobs by financing urban projects. Some mills were torn down and materials were repurposed for new municipal infrastructure. Many cleared areas became parks. The city recovered momentarily in the 1940s due to wartime orders—again the work of the federal government—but the overall trend had been set.

According to architectural scholar Kingston Heath, the hollowed out and vacant mill buildings had a noticeable effect on local perceptions of New Bedford in the postwar period; they served as evidence that the city’s best hour had passed. A turnaround occurred very slowly. “The city began to turn more emphatically than before the Depression to a cod-fishing economy and, later, to an economy based on scallop fishing,” Heath states. “Gradually its residents acquired a different consensus image of place, as fishing boats replaced smokestacks as artifacts of regional expression.” This revival placed the new economy in a longer history revolving around fisheries, a history that could be celebrated and romanticized. Residents seemed eager to bury the ups and downs of textiles from the early twentieth century to the 1950s.

Economic change molded the experience of local Franco-Americans. From the 1920s onward, the community gradually dispersed. Still, New Bedford was home to some sixty Franco-American organizations in the 1940s and that presence would not soon disappear. (In fact, it was and is home to a council of the Richelieu Club, a fraternal and cultural organization founded in 1955.) At the end of the twentieth century, according to Armand Chartier, self-identifying Francos in the city—many of them members of ACA Assurance—were increasingly elderly. A church-going population, this core group was dealt a heavy blow with the 1999 closure of two parishes, including Sacré-Coeur.

French-Canadian heritage survives in New Bedford, but it can no longer count on the institutions that at one time made survivance possible.

On the surface, New Bedford may seem like the archetypal New England textile center, which would explain why it has received comparatively little attention. It is worth studying for its rich industrial heritage, undoubtedly, and even more so for its unique characteristics. Like Salem, New Bedford boasted a fascinating blend of economic activities, with textile manufacturing diverting people from the fisheries for two or three generations. The presence of Acadians and lusophones and the relatively small Irish population made for a cultural setting unlike any other. Franco-Americans developed institutions in New Bedford that served their own specific needs and interests. This group deserves its own story and its spot on the map.

We may hope that this small effort will inspire more researchers and a larger public to discover or rediscover New Bedford’s rich French heritage.

Sources

This post was made possible in part by Evening Standard clippings generously provided by Raymond Patnaude. The databases of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ), Newspapers.com, and the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America also proved essential. Full bibliographical information for primary sources used in this article is available on request.

The work of the federal Industrial Commission resulted in an often-overlooked federal government with extensive information on French Canadians; it appeared in 1901. Volumes 7, 14, and 15 are the most relevant. They are titled Report of the Industrial Commission on the Relations and Conditions of Capital and Labor Employed in Manufactures and General Business (two parts) and Reports of the Industrial Commission on Immigration, Including Testimony, with Review and Digest, and Special Reports, and on Education, Including Testimony, with Review and Digest. They are available on Google Books.

See also standard Franco-American texts: Edouard Hamon, Les Canadiens-français de la Nouvelle-Angleterre (Quebec City: N. S. Hardy, 1891); Alexandre Belisle, Histoire de la presse franco-américaine et des Canadiens-Français aux Etats-Unis (Worcester: L’Opinion publique, 1911); “L’évolution de la race française dans l’Amérique septentrionale,” La Presse, October 23, 1920, 23; Guide officiel des Franco-Américains 1933 (Auburn, R. I.: Albert A. Bélanger, 1933). Barthélemi Noël’s Le directoire français de New Bedford, Mass., 1896 provides immigrants’ addresses and gives a sense of the extent of Canadian business in the city. See, on the Acadians, Clarence d’Entremont, “Acadian Survivance in New England,” in Steeples and Smokestacks: A Collection of Essays on the Franco-American Experience in New England, ed. Claire Quintal (Worcester: Institut français, Assumption College, 1996).

Armand Chartier, “Vie française à New Bedford, Massachusetts,” Cap-aux-Diamants, no. 61 (2000); Kingston Heath, The Patina of Place: The Cultural Weathering of a New England Industrial Landscape (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2001); and Joseph D. Thomas et al., eds., A Picture History of New Bedford, Volume Two, 1925-1980 (New Bedford: Spinner Publications, 2016) are helpful secondary sources.

The City of New Bedford’s website features an inventory of mill properties prepared in the context of new urban planning. Helpful articles from 2014 on the mills’ history and on recent development projects appear on CAI. See also Sean Briody’s text on the Wamsutta Mills on Rhode Tour and this Yahoo news story on St. Anthony’s church.

For more on little-known communities of the French-Canadian diaspora, see prior installments in the “Those Other Franco-Americans” series:

- Exeter, New Hampshire

- Somersworth, New Hampshire

- Berlin, New Hampshire, Part I, Part II, and Part III

- New York State

- Barre, Vermont

- Cohoes, New York, Part I and Part II

- St. Albans, Vermont, Part I and Part II

- Madawaska Region

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - July 23, 2022 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

Pingback: Historical Sources - Fairhaven Office of Tourism