New Bedford gets a raw deal.

Its Franco-Americans even more so.

The city is known for its whaling history and images straight out of Moby Dick—rough, hardy Yankee whalers who in time passed the torch to Portuguese fishermen. Seafarers are more compelling, more romantic figures, we might suppose, than mill workers, whatever their ethnic background. And in the mid-nineteenth century, there was little to suggest that New Bedford’s future held sprawling manufacturing complexes befitting the other mill cities of the Bay State.

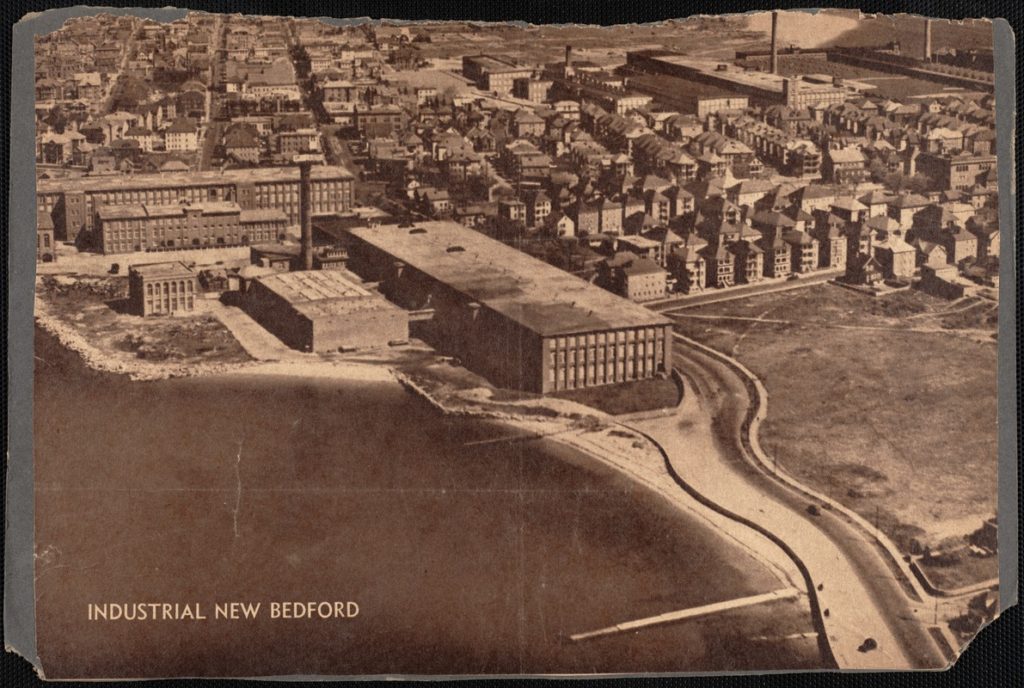

The Acushnet River, stretched into a natural harbor between New Bedford and Fairhaven, seemed eager to send its people into the wider world. It invited the world back. But a great many of the migrants who arrived in the late nineteenth century did not come from beyond the seas. Alerted to new industrial opportunities by mill agents, relatives, and the press, they came by rail from Canada.

Just as New Bedford’s historic importance typically goes unrecognized, so it is with its residents of French-Canadian extraction.

The Making of a Mill City

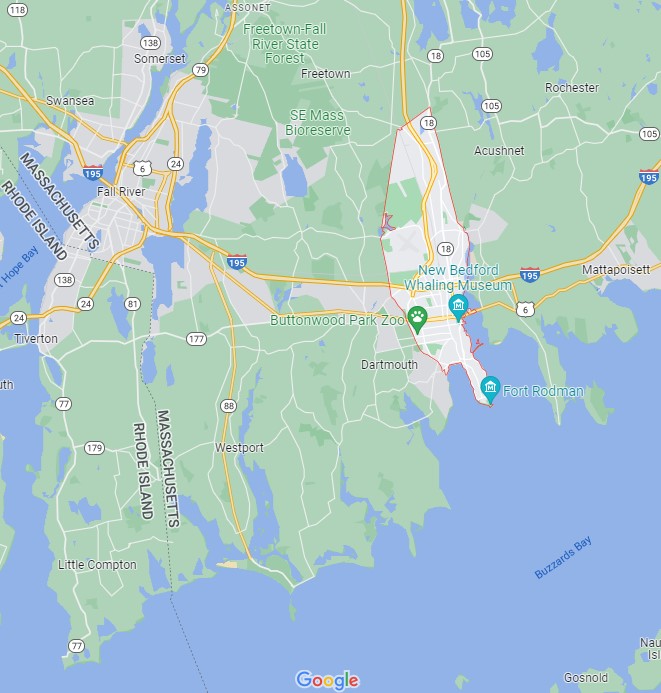

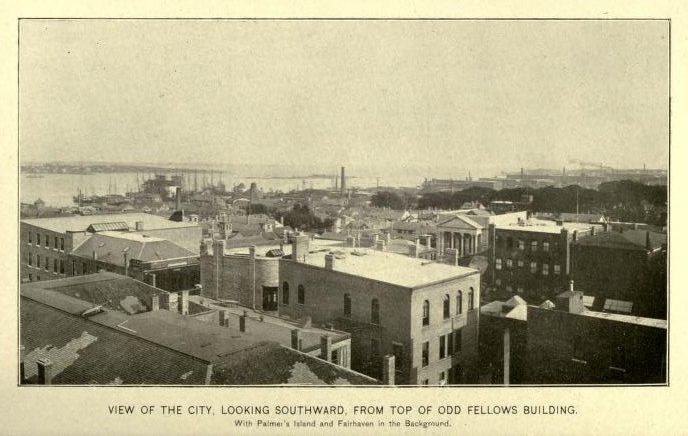

Though the city was already connected by rail to Rhode Island and other Massachusetts centers, the industrial revolution truly came to New Bedford in 1847. The newly-established Wamsutta Company began construction on a cotton mill by the river, north of the city center, in today’s Hicks-Logan sector. Promoters hoped to copy the success of textile manufacturers from Providence to Lowell; the sea seemed to promise easy access to Southern cotton.

Production at the Wamsutta mill began in 1849. But the textile industry as a whole was slow to develop. New Bedford was still a whaling city through and through and it supported an array of complementary industries including oil processing, shipbuilding, and other specialized trades. Whaling reached a point of crisis in the 1870s. Petroleum from Pennsylvania and Ohio undermined demand for whale oil. Declining whale stocks entailed longer and longer journeys at sea. Worse yet, twice during that decade ice floes destroyed New Bedford’s Arctic whaling fleet. By that time, industrialists had slowly carved out an alternative vocation for the city and, as the region recovered from the depression of 1873-1877, manufacturers expanded their operations.

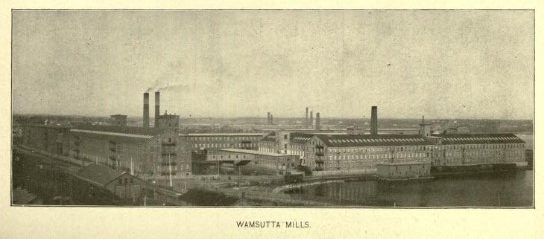

Business boomed in the 1880s. New Bedford’s industrial ascent was as rapid as nearby Fall River’s had been a decade or two earlier. Of all cotton manufacturing centers in the country, it had the fourth highest number of looms in 1893. By the time of the Great War, it was the single largest cotton production center in the United States.

Even from the beginning, businessmen envisioned New Bedford’s facilities as the industrial cutting edge. Unlike many other textile plants of the 1840s, which relied on water-powered turbines, Wamsutta operated on steam power provided by George H. Corliss’s early engines. The city became home to a textile school in the 1890s. More than a trades school, the institution aimed to train men in every facet of mill operations and prepare them for positions of leadership in manufacturing. Local producers also set themselves apart from other factory cities by focusing on fine goods. In the 1920s, Goodyear, Firestone, and Fisk came to the city to process cotton fiber into cord to strengthen automobile tires. The rubber corporations would be among the few to maintain wages while others announced a 10-percent cut in 1928.

The Canadians

Of course, there is no speaking of the textile boom of the late nineteenth century without the immigrant force that made it possible. New Bedford attracted English and Irish mill operatives—as Fall River had. French Canadians represented a quickly growing share of the industrial labor force. A symbolic turning point came in 1876, the year of both the Arctic fleet’s second catastrophe and the consecration of the city’s first French-Canadian parish, Sacré-Coeur. The pipeline to Quebec had been established.

An early twentieth-century report revealed that factories had developed in two large clusters. The South End’s industrial district employed a large number of Portuguese immigrants. French Canadians were mostly drawn to the North End mills, from the Wamsutta complex northward along the Acushnet. Sacré-Coeur sprung up at the corner of Summer and Robeson streets. St. Anthony of Padua was similarly built in sight of the imposing riverside smokestacks.

The rapidly expanding network of ethnic parishes was material evidence that French Canadians were in New Bedford to stay. Some families might still return to Quebec during the summer. Largely, however, they were becoming a stable and settled element of the local population. By 1900, New Bedford’s French-Canadian community of 15,000 was exceeded in size by only four other centers in Massachusetts: Fall River, Lowell, Holyoke, and Worcester. In 1910, less than 20 percent of New Bedford’s population was native-born with two white parents also of American birth. The city then boasted more than 12,000 foreign-born French Canadians and an additional 7,500 residents born to French-Canadian parents; all of the French Canadians now represented more than 20 percent of the local population and formed the largest ethnic group. England, the Atlantic Islands (Azores, Cape Verde), Portugal, and Ireland were the other main sources of immigrants to New Bedford.

This growing community put pressure on available housing stock. The immigrants’ living conditions improved only very slowly. In May 1912, as the Wamsutta Company prepared to pull down some of the oldest tenements, a Sunday Standard article conveyed the living conditions that met the first immigrants to the city: “plain square brick houses, four tenements in each, each tenement consisting of three rooms on a floor and two attic rooms, without gas or bathrooms and with antiquated plumbing, until recent years with the privies in the backyard. The houses were substantially built but they were of the plainest sort.” Older residents connected with whaling looked down on the mills and this type of housing, yet the next phase of development brought few improvements.

In the 1880s, the emergence of private contractors enabled manufacturers to gradually get out of the housing business. The new tenements were not brick, but wood structures built on the cheap; they were dark and cramped. Many were built in the immediate vicinity of the factories of the North End mill district. The twentieth century brought the iconic triple deckers found all across the Northeast. Life in these sturdier, more welcoming buildings came with a cost: they were two to three times more expensive to rent than the private tenements built a few decades earlier.

Working conditions improved even more slowly than housing. When workers went on strike, wages and fines were almost always the issue, not to the type of work, which may have seemed immutable. Such was the case in 1898 when, in the middle of winter, a general walkout in New Bedford paralyzed the whole industry except for the yarn mills. (Biddeford, Maine, workers also struck.) The workers’ gritty determination to reverse a 10-percent wage cut—at a time of renewed prosperity—was reflected in the length of the strike. It lasted more than ten weeks.

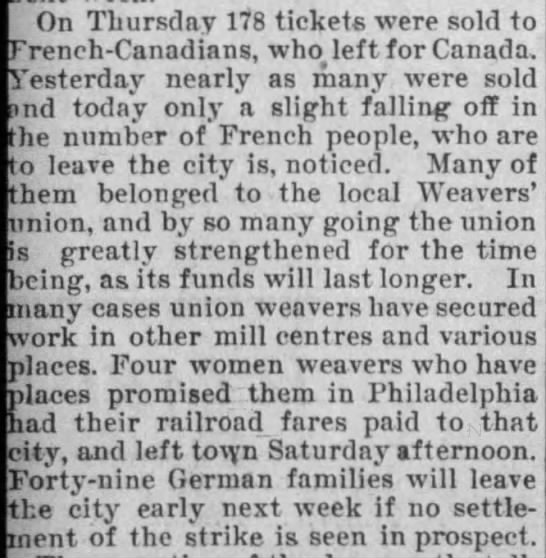

Much more research is needed on French Canadians’ gradual entry in the American labor movement—in New Bedford but also all across the Northeast. In some areas they appear to have shed their image as strikebreakers and become pillars of labor unions in less than a generation. Elsewhere, the story is more complicated. Everything suggests that organized labor made inroads among French Canadians in the Fall River–New Bedford area between 1890 and 1910. The strike of 1898 reflects a moment of transition. Perhaps out of genuine sympathy, perhaps to avoid violence, Canadians walked out alongside other workers. But rather than remain idle, contemporary reports show that many traveled to Canada for the duration of the strike. In January and February, there was likely little work to be had north of the border. They at least visited family and explored other opportunities, some simply going to other industrial cities. Their departure meant New Bedford manufacturers could not resume operations at a moment’s notice; it also meant more money in union coffers and more assistance to those workers who stayed put.

Culture

New Bedford’s Franco-American community built cultural institutions similar to those of other New England cities, but with a twist that reflected its unique, local circumstances. For one thing, this was a community that developed slightly later than its counterparts elsewhere in the U.S. Northeast. When Father Edouard Hamon published his famous report on the network of French-Canadian parishes in 1891—a report that sparked worry about immigration in Anglo-Protestant circles—, the institutions of survivance in the city were still in their infancy.

The church of Sacré-Coeur was in its fifteenth year of activity and a second ethnic parish, Saint-Hyacinthe, located at the South End, had only just been established. St. Anthony of Padua parish followed in the 1890s and reflected the growing means, confidence, and settled character of the French Canadians of New Bedford. Built in hopes that it would one day serve as a cathedral and an episcopal see, St. Anthony’s church was not completed until 1912. New Bedford, we know, did not get its own bishop. Fall River won that honor in 1904 and sheer numbers would never justify the creation of a new diocese less than fifteen miles away in its sister-city.

With the churches came the parish schools. In the 1890s, a convent school operated by the Sisters of Holy Cross boasted 615 pupils. Religious influence in the lives of Franco-Americans and other Catholics also came in less palpable ways. Following pressure from the teaching sisters, in 1914, the trustees of the local public library selected Amanda Dion as an assistant at the North End branch. Dion was a high school graduate; she had been educated in Quebec and had worked as a teacher. We may also suspect that the Sisters of Holy Cross believed her to be of impeccable moral character. Dion’s name was put forth not only to provide symbolic visibility and representation to Catholics and assist francophones. The nuns and their supporters were seeking a person who would monitor materials requested by Catholic patrons and, quite explicitly, prevent them from checking out materials proscribed by the Church. Dion’s selection was supported by Mayor Charles S. Ashley, seemingly a regular friend of Franco-Americans, and garnered the trustees’ endorsement. That this person would enforce Catholic strictures at a public institution passed with remarkably little controversy.

This article will conclude in two weeks. A list of sources for these posts will be available with the second.

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - July 8, 2022 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

an interesting and informative article. I never thought of New Bedford as having a large French Canadian population. I erroneously considered it a Portuguese whaling community, which is part of its history, but not all.

My father came from Quebec in 1910 and my mother’s parents came in 1905.

My dad and mom both worked at wamsutta mills.new bedford was a great place to grow up.

Pingback: Historical Sources - Fairhaven Office of Tourism

Interesting read. My maternal grandfather (Doyon) was born in New Bedford in 1929. His family returned to Quebec when he was still a child. Having grown up in Montreal in a Québécois family, the history of Franco-Americans in New England has always fascinated me.