It is not quite the mountainous wilderness—an Appalachia of the north—that I had expected. Yet, in my experience, after hours on the road, as each hill softly yields to another, you do sense that you are entering a different world. Push beyond the highways and you may see signs for Frenchville, Ouellette, and New Canada. Stray far enough from the beaten path and you could end up in Little Canada.

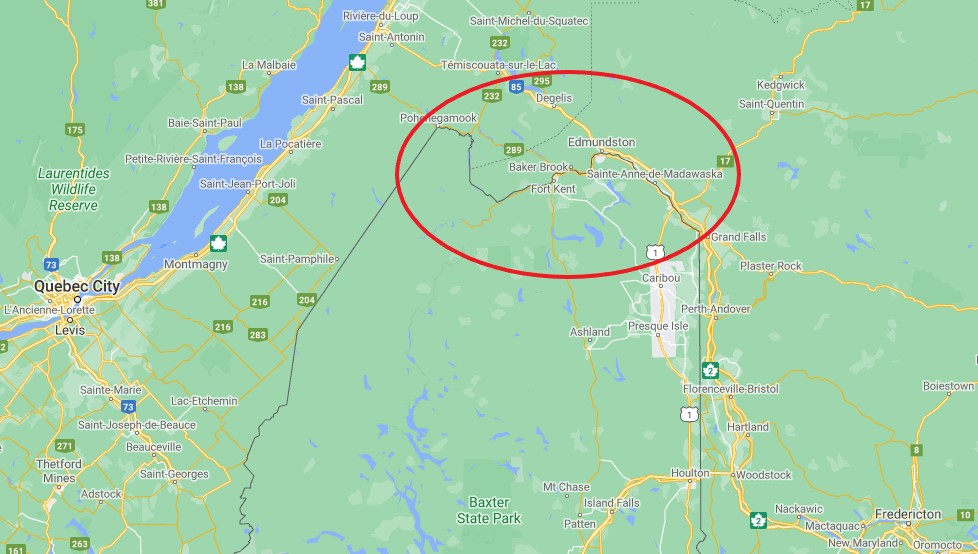

Even such small glimpses of the geography and cultures of the Upper St. John River—where Quebec, Maine, and New Brunswick meet—help us understand the unique character of the area. It’s not quite here, not quite there, but be sure to bring your passport.

This region, the Madawaska region, has long defied firm national identities and boundaries. Britain and the United States could not agree on ownership when its settler culture and economy developed. As we often hear, whereas late nineteenth-century French Canadians crossed the border to find employment in New England, the border crossed the people of the Madawaska.

The title of the most authoritative study of the region’s history, Béatrice Craig and Max Dagenais’s Land in Between, captures the peripheral character of the Madawaska. In fact, our theoretical categories failed to do justice to its uniqueness until the advent of borderland studies in the 1980s—though the concept of borderlands tends to corroborate the region’s distinctiveness. In the field of Franco-American history, when the Upper St. John valley is acknowledged, it surfaces as a curiosity—an interesting but unnecessary appendix to the cities where the story really unfolds.

A quick survey of the region’s nineteenth-century history may help us shed light on that distinctiveness—and to nuance it.

* * *

From time immemorial were the land and its original occupants. The Indigenous bands that inhabited the region left an archeological record, but the epidemics and conflicts sparked by the beginning of European colonization and the subsequent displacement leave a lot of uncertainty about cultural changes. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, when European encroachment in the Upper St. John valley became consistent, the Wəlastəkwewiyik or Maliseet people were well established. Local bands experienced cultural fusion as Eastern Abenaki and Mi’kmaq escaping land loss fled into the region.

The primary means of communication and conveyance between the new French colonies of Canada and Acadia were the St. Lawrence River and the gulf that bears its name. But as early as the 1680s, authorities in Quebec City were aware of what we might imperfectly call the overland route, consisting of the St. John River up to present-day Edmundston; the Madawaska River; Lake Témiscouata; and the “grand portage” from the lake down to the St. Lawrence near Rivière-du-Loup.

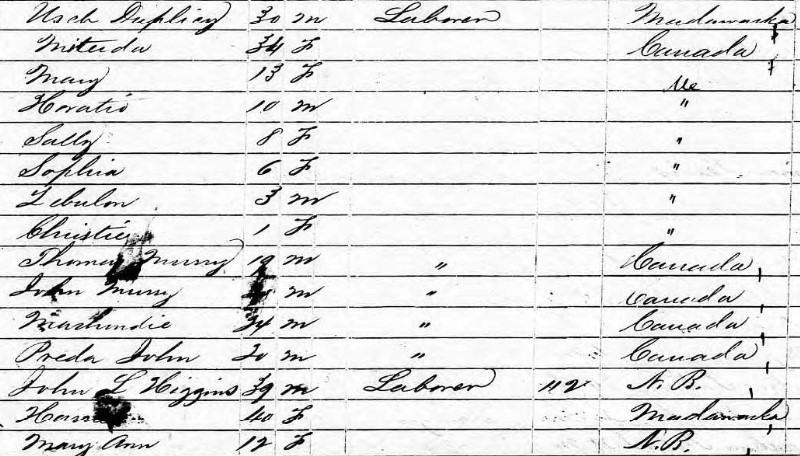

The Madawaska region drew fur traders through the colonial period; efforts at permanent settlement occurred only towards the end of the eighteenth century, when Acadian families began petitioning for land grants along the Upper St. John. It was long believed that the influx of Loyalists in southern New Brunswick in the 1780s had displaced Acadians still reeling from the Deportation. The documentary record reveals, however, that in the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War, Acadian families earned legal title to the lands they occupied near present-day Fredericton. The Loyalists’ arrival did not cause a smaller, more local deportation. It did heighten competition for land and proactive Acadian families began seeking new opportunities to “settle” their children. From the mid-1780s, they requested and obtained the right—from colonial authorities, not the original occupants of the land—to settle along the Upper St. John.

Another long-held misconception is that the French-heritage people of that region were, and are, quite simply Acadians. But the period of Acadian settlement was brief, ending at the very beginning of the nineteenth century. From the 1820s, in small, irregular waves, French Canadians from the St. Lawrence River valley joined their colonial-era cousins. This migratory movement was more numerous. The Acadians’ customs were preserved and maintained because these settlers were, by then, well established, and the French-Canadian migration was gradual enough as to not overturn the prevalent culture. Acadian families tended to look down on the poor French-Canadian migrants who didn’t have kinship ties in the region. But French Canadians were able to slowly accumulate capital and over time intermarriage did occur. The Upper St. John valley remains part of the Acadian cultural universe, but, ancestrally, its residents are to a great extent French-Canadian. It may in fact be this gradual infusion of other French-heritage people—and not merely distance—that sets the Madawaska apart from Moncton or la péninsule acadienne.

Economically, the tentacles of international capitalism reached into the region after 1825. Small-scale trade with Quebec City and Fredericton (the Madawaska’s two natural outlets) was then well entrenched, difficult though it was. With the granting of the first licenses for tracts, the timber trade overtook agriculture as an engine of development. Like other regions in the St. Lawrence periphery, it enabled young men to earn seasonal wages—either to supplement a family’s agricultural income or to save up before marrying. French Canadians poured in. Timber helped put money in local stores and raised the value of adjoining lands. It created opportunities. It also created conflict.

As noted, Britain and the United States could not agree on the exact location of the border—despite many efforts to settle the matter in the decades after 1783, when Britain recognized American independence and the international boundary came into being. Local residents were generally unconcerned with its placement. In this era, rather than separating them, the St. John River brought people together. It was a giant avenue that compensated for the absence of proper roads. Wherever the border would fall, it was unlikely to disrupt the economic or social significance of the river. For a long time, the boundary was also an afterthought to decisionmakers in Washington and London. The rise of a profitable timber trade and the saber-rattling of Maine legislators forced the issue.

Attempts by Maine and New Brunswick officials to assert their respective authority in the region led to the Aroostook War, which coincided with the Patriot War that disrupted the border farther west. The conflict in the Madawaska region was bloodless, but it led to momentary militarization. The Great Republic was then traversing an acute economic crisis; it did not have the military strength or willpower to fight a third Anglo-American war in as many generations. The national interest called for compromise. The new boundary line established by the Webster-Ashburton agreement of 1842 frustrated the hopes of Maine jingoists, but U.S. merchants retained special trade privileges when floating lumber on the Canadian side of the border.

The border came, the borderland endured. This was a period of weak central state authority. In rural areas, the state only appeared in the form of a sheriff, a customs agent, and the owner of a few coaches who had won a license to carry mail. The militia might only exist on paper. The border settlement provided legal clarity but, until the twentieth century, changed little in the activities of local residents. The people of the Madawaska were proactive in seeking on the other bank of the St. John that which they could not find on their own. There was little to check their movement. (The U.S. Border Patrol was a creation of the 1920s.)

Integration in a larger economic, cultural, and political world came slowly—typically accompanying technological advances and the expansion of government responsibilities. The Province of Canada began granting lands along the new border in the 1840s and, like New Brunswick, invested in roads. Women religious arrived in the 1850s to take charge of Catholic education. The economy diversified; a market for sawn lumber (replacing the extraction of “ton timber”) prompted the construction of mills on both sides of the St. John; and at the turn of the century pulp and paper found encouragement in New Brunswick. A railway from the east finally reached Edmundston in 1878 (two years after the completion of the Intercolonial), whereas Van Buren was at last connected to American centers farther south in 1899. Two more decades would elapse before an international bridge spanned the St. John River.

This cursory history suggests that change came gradually to the Madawaska region. There were economic shocks and governments used coercive means to mold the area. But, while other North American borderlands were quickly swept away through war, mass immigration, and large development projects, the Upper St. John’s French communities and hybrid identities survived. This is not to say that the region is today an artefact of a different era, for it changed with the world around it. It has, on the other hand, remained a perpetual hinterland whose transnational culture escapes easy categorization.

* * *

Scholarship on the Madawaska has highlighted its distinctiveness—perhaps with reason. But we should consider how much of this story is constructed and whether the evidence might lead us to reevaluate the characteristics that relegate the Madawaska to the margins of our fields of study, just as it lies in an apparent geographical margin. What if the Madawaska was a normal society—meaning one that fits patterns of development and cultural experiences seen in other settler societies across North America? What if the unique character I’ve alluded to is more imagination than reality?

Scholars have put the same questions to Quebec. How distinctive is Quebec society? How much does it share with its larger North American setting? Ronald Rudin famously wrote about “the search for a normal society” in Quebec historical scholarship in the 1990s. I raise the same idea and use the same term (normal) not as a value judgment, but to identify, like the works that Rudin surveys, the extent of those commonalities. We can highlight the common ground without denying the richness of the local culture. More than that, recognition of a certain level of “normalcy” can serve as a powerful analytical tool; it can provide a frame of reference that is wholly lacking when an entire people is depicted as sui generis.

The work of the leading scholar of Madawaska history, the aforenamed Béatrice Craig, recognizes the value of the borderland perspective. From the early nineteenth century, when their settlements cohered, the Upper St. John River and its hinterland formed a liminal economic space that escaped formal state authority and blended cultures. However, Craig’s authorial voice comes across most clearly when she “normalizes” the region. For instance, with Dagenais, she states that early nineteenth-century settlers in the region “were as much part of the political system as their social standing, education, and, until 1830, religion, allowed. In this respect, they were no different from other residents of [New Brunswick].”

From these historians’ work, it is easy to draw parallels between the crisis of agriculture that struck Lower Canada (later Quebec) in the first half of the nineteenth century and the process of agricultural diversification that occurred on the St. John River. In addition, the development of the agroforestry sector in the Madawaska fits a pattern witnessed from Maine to Michigan. But it’s not just a matter of similarities. The region evolved not in spite of, but within a larger network of exchange and such connections across boundaries challenge preconceived ideas about an isolated and closed society. The timber trade opened those connections. As Craig and Dagenais explain,

By the mid-1800s, a Valley resident could eat bread made from Upper Canadian flour (ground, perhaps, from American wheat) with Canadian mess pork or Newfoundland cod, drink East Indian tea sweetened with West Indian sugar in English earthenware, use American-made screws and nails manufactured in New Brunswick, wear shirts or aprons made of American cotton, don shoes mass-produced in New Brunswick or moccasins made by Natives, and wear homespun clothes to plow the fields or milk the cows. The Madawaska consumer, like the Madawaska producer, was blending local and regional goods with continental and transatlantic ones.

Beyond material culture, residents’ kinship ties stretched from the Côte-du-Sud and the lower St. Lawrence to southern New Brunswick; soon, their familial universe came to include the mini-mill towns of Orono and Old Town. The “in-betweenness” of the Madawaska was a stepping stone between rural Quebec and a more distinctly American environment.

Such claims are sprinkled throughout The Land in Between and Craig has continued to explore connections to other societies in a recent standalone article in Acadiensis. Here she connects Madawaska life to the farming communities of colonial New England, the Lower Canadian periphery, and the western “frontier.” This is a relatively new front in the study of the Madawaska and it certainly promises new insights. Even if we work from a borderland perspective, there would be clear benefits to comparative research that brings the Eastern Townships of Quebec, the Detroit region, and the American Southwest into the conversation.

Non-scholars might be surprised by the amount of debate that takes place between historians and how little of it has to do with facts. Such debates generally revolve around interpretation—that is, how we assemble the facts and where we place our emphasis. The discussion is, regrettably, rather weak when it comes to the Madawaska. Greater attention to the way in which we pitch the story and what we choose to emphasize may help those of us who aren’t from the region, but have great affection for it, do justice to its rich and fascinating history.

Sources

Numerous historians, researchers, and archivists have helped tell the Madawaskayan story since the publication of Thomas Albert’s pioneering Histoire du Madawaska (1920). Without denying the collaborative nature of the historical enterprise, my post draws especially from Béatrice Craig’s work due to its breadth, its influence, and its sustained engagement with historiographical debates. Beyond The Land in Between (2009), see particularly Craig’s “Immigrants in a Frontier Community: Madawaska 1785-1850,” Histoire sociale/Social History (1986); “Agriculture and the Lumberman’s Frontier in the Upper St. John Valley, 1800-70,” Journal of Forest History (1988); and “Le Madawaska entre marche et région frontalière au 19e siècle ou les limites de la construction étatique américaine,” Acadiensis (2016).

Ronald Rudin’s “Revisionism and the Search for a Normal Society: A Critique of Recent Quebec Historical Writing” appeared in the Canadian History Review in 1992. I encourage everyone to learn more about the culture and claims of the original occupants of the Madawaska region; the website of the local Maliseet First Nation is a good starting point.

My John F. Kennedy and the Politics of Faith is available from the University Press of Kansas. Consider buying from the publisher or supporting your locally-owned bookstore.

For more on little-known communities of the French-Canadian diaspora, see prior installments in the “Those Other Franco-Americans” series:

- Exeter, New Hampshire

- Somersworth, New Hampshire

- Berlin, New Hampshire, Part I, Part II, and Part III

- New York State

- Barre, Vermont

- Cohoes, New York, Part I and Part II

- St. Albans, Vermont, Part I and Part II

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - May 15, 2021 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

Pingback: Make a Statement with Franco-American Flags – Moderne Francos