We are fast approaching the second anniversary of the publication of “Tout nous serait possible”: Une histoire politique des Franco-Américains, 1874-1945, the first full-length regional synthesis of Franco-Americans’ political involvement. I am very grateful for the support of the Presses de l’Université Laval, generous reviews, and readers’ willingness to give it their time and attention. As an expression of my appreciation, for English-language readers, below is a translated excerpt on the challenges to political organization among the Franco-Americans of Connecticut.

* * *

The naturalization movement was nowhere so slow and difficult as in Connecticut. The state’s unique position has given it an unenviable place in our historical narrative; it typically receives only passing attention in Franco-American research. Even in the 1880s and 1890s, different circumstances set it apart from Franco-American life in neighboring states and help explain the limited political influence of immigrants and subsequent generations. On the other hand, while Canadians’ experience in this state does not entirely represent what immigrants experienced elsewhere, it does provide a microcosm of the many barriers to naturalization in the Northeast.

The factors that delayed naturalization in Connecticut had caused the same challenges in other areas a few years earlier. The migratory flow had something to do with it: in 1891, Father Edouard Hamon ranked Connecticut last among Northeastern states in terms of French-Canadian population. Its 24,000 residents of French-Canadian ancestry put it behind even the small states of Vermont and Rhode Island. These migrants’ geographical dispersion made their political and cultural organization all the more difficult. Amounting to only a small share of the major centers’ populations (in Bridgeport, New Haven, and Hartford for instance) and separated into numerous industrial hamlets throughout the state, the Franco-Americans of Connecticut could not imagine a common destiny with the comparable ease of their compatriots in Massachusetts, for example.

The hearing held by Colonel Carroll D. Wright in Boston in 1881 revealed other challenges weighing against the organization and public influence of Connecticut’s working classes. Edouard L’Hérault, a constable from Fall River who had recently visited that state, explained that several factories recruited directly in Quebec and paid workers’ travel expenses. The “imported” workers and their families were at the mercy of companies that kept them in a position of financial dependency. These workers dreamed of the moment they would settle their accounts and settle elsewhere under better conditions. Even if they had no intention of returning to Canada, many migrants expected further moves, hence the futility of pursuing naturalization in Connecticut.

Taken together, these conditions worked against the establishment of Canadian professionals and businessmen who might carve out a francophone clientele. Industrial work was plentiful, but a doctor would more easily find his place in the Lowells of the world. The weakness of the middle class extended to societies dedicated to benevolence, education, survivance, and naturalization. The virtual absence of a French-speaking press highlighted the difficulty of organizing and reaching Connecticut’s “Francos.” Le Courrier du Connecticut, a creation of businessman Benjamin Lenthier with minimal local content, appeared briefly in 1892. Before the turn of the century, newspapers were founded in Norwich and Waterbury, but both were short-lived. Educated immigrants had to depend on newspapers from Worcester, Massachusetts, the major Franco-American center closest to the communities of Putnam and Grosvenordale. After the disappearance (in the winter of 1892-1893) of Le Travailleur, a creation of Ferdinand Gagnon, who had taken an interest in Connecticut affairs, people preferred to subscribe to another Worcester paper. L’Opinion publique, founded in 1893 by the Belisle family, knew how to reach the Franco-American population of Connecticut and sent journalists to important events in the state. As for cultural mobilization, it was pointed out in 1886 that Connecticut was the last to organize national (ethnic) state conventions. Still, delegates managed to meet almost every year from 1885 until the end of the century.

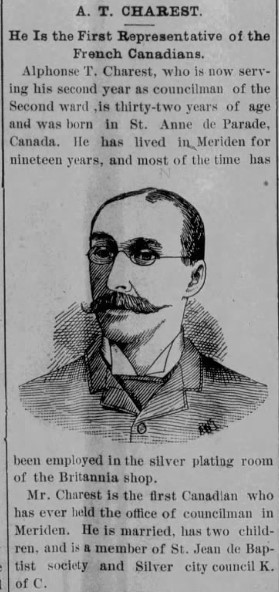

State-level congresses expressed the same interests and concerns as the major regional conventions. Beyond education and support for a national (French-Canadian) clergy, naturalization was of primary importance for the elite, which sought to assert its prestige as well as the potential influence of the Franco-American population. The subject figured on the agenda of each of the conventions held in the state from 1885. Moreover, at the inaugural convention, Fall River attorney Hugo Dubuque highlighted the advantages of naturalization, pointed to the rights that French Canadians must claim, and provided arguments that would challenge the nativistic rhetoric under which the migrants labored. Omer Larue would later offer a much more tangible justification for citizenship: before obtaining the vote, in some French-Canadian neighborhoods, civic officials had neglected the streets. Suffrage now gave them “a level playing field” and helped sustain the value of Franco-American property. In 1886, a committee went further and declared “that naturalization is the remedy to all the ills of which we complain.”

However, soon after, some figures complained of the difficulty of forming new Franco-American organizations, in particular naturalization clubs; the state convention of 1887 made this cause the responsibility of the existing societies. The following elections witnessed increased political involvement. But this strategy was set back by the reluctance of sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste whose means were limited and whose members wished to avoid political subjects. Physician Charles Leclaire had his turn in Danielson, in 1891, in commenting on the deep apathy of Franco-Americans with regard to naturalization and American politics. The cycle continued: a more pronounced interest in politics arose again during the campaign of 1892. At that time, nearly one thousand new French-Canadian voters were favoring Democratic presidential candidate Grover Cleveland in Windham and New London counties, where the centers of Putnam, Danielson, and Norwich were located. Sometimes, civic officials addressed ethnic congresses with a word of welcome and offered attendees recognition; still, Canadians did not benefit from equal interest from the party machinery in the state.

Thus, with respect to naturalization and political involvement, French Canadians fell prey to a vicious cycle—the ethnic social universe and the American civic universe only coming together very slowly, despite the efforts of an influence-hungry elite. The Connecticut case amplifies the challenges faced throughout the Northeast without distorting their nature. Everywhere, politically, the mobility of migrants and the weaknesses of the Franco-American institutional network were problems. Edouard L’Hérault also pointed to an obstacle that was just as important and certainly regional in scope: the need to learn English, which was difficult for the men aged 30 and over who had only ever known French. Evening schools were organized throughout the Northeast, but it is impossible to measure their effect on the progress of naturalization. Ultimately, it was geographical concentration, the presence of a press and a professional middle class, and the formation of a robust institutional network that enabled the communities of Fall River and Woonsocket to more quickly overcome these obstacles, which for a long time undermined Franco-American political influence in peripheral regions.

The mobility problem gradually diminished, especially with the return to prosperity on the eve of the 1881 hearing. The figures produced by William MacDonald in 1898 marked a deficit in relation to the “naturalizable” population, but confirmed the growing importance of Franco-Americans in certain districts and in tight races. This catch-up in the rate of naturalization and voter registration continued after 1900. In Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1910, Franco-Americans represented 27 percent of the population and 20 percent of voters, a substantial gain. It must be recognized, however, that at this time a large number of “Francos” born on U.S. soil (and thus citizens) were reaching adulthood. The eventual political prominence of Canadians owed perhaps more to this generational transition than to the naturalization of immigrants.

Leave a Reply