The arrival of European peoples in the Americas had a cataclysmic effect on the original occupants of the land. Initially, the devastation of Indigenous nations owed primarily to the spread of unknown diseases. As Europeans became more numerous and asserted their influence, Natives suffered from war, the loss of their ancestral territory, heightened competition for scarce resources with other Indigenous groups, growing dependency on European trade goods for survival, the tragic effect of alcohol and firearms in their communities, and ecological destruction.

In subsequent centuries, the position of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas hardly improved. They contended with further dispossession, enslavement, biological warfare, and attempts to deprive them of their ancestral culture.

For most of the intervening time, political and intellectual elites eagerly presented these events as the natural course of things. Providentially, the “Indian” vanished to make room for “civilization” and “religion” (narrowly defined). Settler states aimed to maintain a separation between whites and Indigenous groups and erase the culture of the latter. In the last sixty years, at a snail’s pace, and often in very unsatisfactory ways, attitudes and policies concerning peoples who lived here from time immemorial have shifted. In the process, new and equally unhelpful views have emerged and they merit their own critical scrutiny.

In the colonial period, an interesting tension underlay the approach of each colonizing power towards the Natives of America. While claiming cultural superiority over the Natives and their own right to conquer and occupy, Europeans played up humanitarian concerns. Here I do not refer to the likes of Bartolomé de las Casas, who famously denounced the atrocities committed by his own country. Rather, Europeans vied with one another for the moral high ground in Native-settler relations. The clearest example is the emergence of the Black Legend, a powerful narrative in English circles. This “legend” emphasized Spanish brutality in Central and South America and offered English rule as a mild alternative. Claims to humanitarian sentiment would not be borne out by actual practice as the English colonies expanded from scattered settlements along the Atlantic.

Juxtaposed with Spanish and English colonization, the French have often appeared as a benign presence on the continent—the colonial power and colonists who enjoyed the friendliest relations with Native groups. In recent generations, that has been a particular point of pride among French-heritage people in North America. In the race to determine who was “least bad,” their case has found corroboration in Richard White’s The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815, first published in 1991.

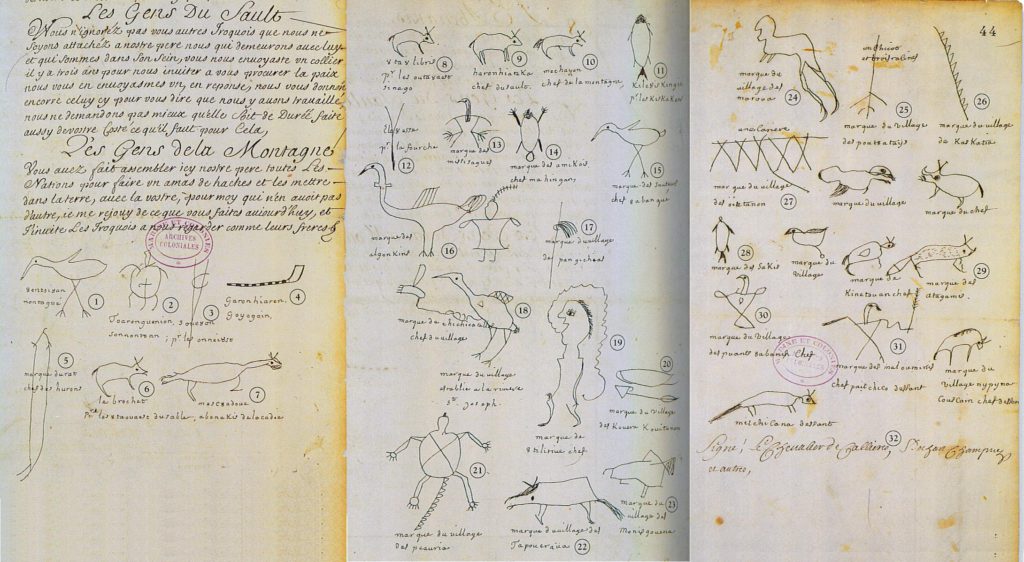

According to White, the Great Lakes were not only a geographical middle ground where Natives and Europeans were evenly matched and had to accommodate one another. The two sides developed a cultural middle ground: a common set of customs, rituals, and ideas, sometimes based on misunderstandings, that enabled them to trade and work together in war as in peace. In other words, this was a symbolic space that helped affirm their commitment to one another. French political authorities, traders, and missionaries unquestionably devoted more time and energy to the cultivation of this middle ground than their English and Spanish counterparts. After the 1760s, British representatives operating in the Great Lakes region and some American colonists belatedly learned from the French. The War of 1812 and the subsequent mass arrival of white settlers ended accommodationist practices.

This collapse of the middle ground suggests that population sizes and economics had a major part in defining Native-settler relations. In French colonies, permanent settlement occurred slowly and in relatively small numbers. When Montreal surrendered to Jeffery Amherst in 1760, residents of New France amounted to approximately 5 percent of the Thirteen Colonies’ combined population. It was a smaller, thinly settled colony; it was more vulnerable and far more dependent on Indigenous groups with regard to both trade and security.

It would, however, be easy to extrapolate White’s claims beyond his intent—that the French were inherently more friendly, more respectful, and more open to Indigenous customs. This view holds sway on internet discussion boards and in popular works of history, sometimes self-published, sometimes published by presses that do not have a rigorous fact-checking process. Single-minded focus on the proximity and friendship between French and Natives (crowding out any discussion of conflict) is enhanced by certain genealogical researchers who seek exotic roots and who amplify the few, exceptional Indigenous individuals in their family tree.

This is a radical shift from depictions of Indigenous peoples in classic works of Acadian and French-Canadian history. Setting aside easy references to the clerical and ethnic nationalism of Lionel Groulx, we might consider amateur historian Pascal Poirier. The first Acadian to serve in the Canadian Senate, Poirier penned a long treatise on the “pure blood” of his people. His Origine des Acadiens (1874) argued that no biological mixing of French-heritage people and Native groups had occurred to any significant extent. “The Acadian race is not only exempt of any mixing with the sauvages,” he wrote, “but it is, of all the white races that today inhabit the American continent, the one whose purity [intégrité] of blood has perhaps been the best conserved in all respects.” Evidently, racial purity was not a concern merely of Anglo-Saxonists. Poirier and others insisted on a hard line of separation between sauvages and civilisés.

Poirier was not an outlier, in his time. The recent historical work of Catherine Larochelle shows that this view, if advanced most provocatively by elites, was disseminated in Quebec’s public schools in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There is ample evidence that French Canadians were complicit in colonialist and assimilatory practices in the nineteenth-century West as well. Mythmakers and historians sought to provide justification for such policies and to read back in time the separation of Natives and whites.

Nuance is the name of the game, here, and this fairly lengthy blog post cannot even come close to doing justice to the full complexity of Native-French relations. That is partly the point: we should recognize that full complexity and use it to challenge inherited narratives that offer misleading views of French North America—one, a narrative about uncivilized barbarians; the other, about a utopian world where French and Indigenous were undifferentiated.

French settlers learned from their Indigenous neighbors; the latter’s knowledge and know-how proved, in a paradoxical way, essential to the success of the colonizing society. New France relied on commercial, political, and military ties with Native groups. In the colonial era, there were “country marriages” between male fur trades and women of allied nations.

On the other hand, the prominent demographer Hubert Charbonneau has persuasively shown how few Native-settler marriages were in established communities along the St. Lawrence River. The traditional economic activities and lifestyles of each group were generally unappealing to the other.

These differences are at the heart of William Wicken’s “Re-examining Mi’kmaq-Acadian Relations, 1635-1755,” published in an edited collection in 1998. Wicken “raise[s] doubts about the extent of intermarriage and, more generally, about the long-term convergence of Acadian and Mi’kmaq interests.” In the 1750s, relations between these two groups reached their breaking point. The Acadian population was growing quickly and required more and more land to support itself. The conflict became territorial and the cultural chasm between the groups deepened due to the absence of common social spaces (including marriages). Acadians’ desire to remain neutral while the Mi’kmaq aligned themselves with the colonial interests of the French on Cape Breton amplified the hostility.

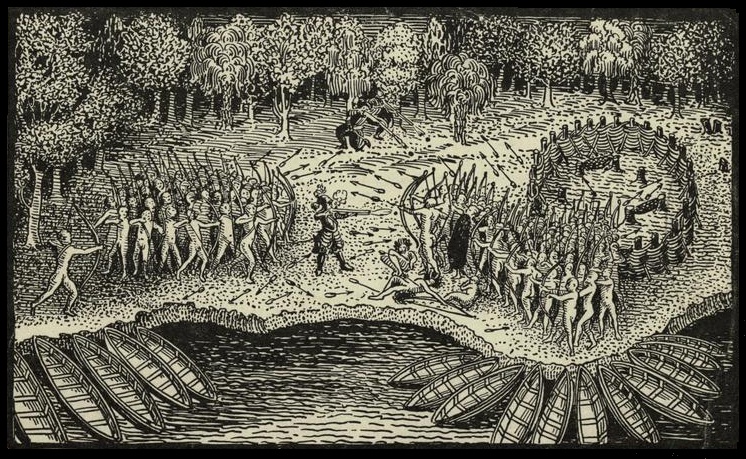

In American Colonies (2001), historian Alan Taylor shows that the Native-French middle ground was not a universal model. Throughout North America, the French were selective and strategic in their friendship with First Nations. When they forged alliances, they also earned the enmity of other Indigenous groups and were thus drawn into existing rivalries. They fulfilled the expectations of their alliances—and protected their own credibility, influence, and commerce—by helping some nations punish and destroy others. History has recorded the friendly relations, and much less the punishing incursions against rivals (the decimation of the Fox in early eighteenth century, for instance). In his study of French Louisiana, Taylor goes further. “[A]s soon as the French grew secure in greater numbers,” he notes, “they abandoned gratitude. On their periphery, the French posed as emancipators of Indians enslaved by the English, but at the core they imposed slavery on any of the Petites Nations that defied their power.”[1]

The point here is not to create a new Black Legend that would focus exclusively on French depredations. Rather, we should think of Native-French relations as complex—determined by time and place and by the evolving interests of each group. More than other European groups, the French made compromises based on power relations. Sometimes, such situations opened opportunities for better understanding; sometimes they created obstacles.

Recognition of this complex past may lead French-heritage people and other settler communities to confront a messy and sometimes uncomfortable past. The primary purpose of history is not, in my view, to apportion praise or blame. It can, however, help us understand how identities develop—and understand others on their own terms. It can help us gain perspective on historic inequities and encourage self-study, self-scrutiny.

It may, at last, guard us from conflating settler and Indigenous experiences on this continent. In recent times, as noted above, some French Canadians have gone in search of Huron, Abenaki, Mi’kmaq (etc.) ancestors. Some of them claim to be métis or Métis either on the basis of tenuous genealogical connections or of an obscure oral tradition. This is worth noting because descendants of Pierre Miville don’t claim to be Swiss; we witness specifically an appropriation of an “exotic” Native identity. As Darryl Leroux explains in Distorted Descent (2019), it is also worrisome because such claims are sometimes translated politically, displacing the legitimate concerns of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis groups—to use, again, the Canadian terminology. Indigenous groups would be the first to state that biological descent doesn’t make identity. Ethnicity is about customs, culture, lived experience, and kinship networks in the present day.

A broader and more balanced historical account of Native-French relations will yield a firmer foundation on which we can rest identity claims and a new, just, equitable middle ground—in the present day.

Further Reading

- Charles C. Mann, “1491,” The Atlantic (2002).

- Thomas King, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America (2012).

[1] There were also Indigenous slaves (“panis”) in Montreal. In his People of New France (1997), Allan Greer notes that there were 147 such individuals in French-controlled Illinois country in the 1750s. This group was still dwarfed by a much larger population of slaves of African descent.

Love your podcasts. I have learned so much from you!

Maybe you should charge me tuition!