Three month ago, this blog plunged into the Upper St. John Valley, an area whose history often falls on the margins of existing narratives. The hard work of reconstructing the history of the Madawaska, its relationship with neighboring regions, and its place within empires is complicated by surviving sources that tell (at best) a partial story. Until the end of the nineteenth century, a small proportion of the region’s population had the literacy skills and inclinations that would have produced a large documentary record. Scholars must triangulate from material artifacts, records produced by the Catholic Church or government bodies, and the accounts of outsiders who passed through the region.

These accounts or travel narratives were often contradictory and regularly disparaging. Their prejudices do not necessarily mean, however, that we should reject them out of hand—tempting as that may be, in our current climate of opinion. As we read between the lines, we find what the authors thought to be a “normal” society; we also find what was and wasn’t possible for the French-heritage communities as they became increasingly entwined with British, Canadian, and American interests. From the early nineteenth century to the 1860s, these disparaging sources expose moments when history might have turned and set a new course for intercultural relations between the Valley and the surrounding world.

1812

Permanent white settlement of the Upper St. John or Madawaska region began in the 1780s. But not until the 1820s, with the establishment of the lumber industry, would the river become a major commercial artery. Until then, as Joseph-Octave Plessis found, the region was relatively isolated and had to be self-sustaining with respect to its basic economic needs.

As we have seen, Plessis was the bishop of Quebec and would not be confined to his episcopal palace. He visited the Madawaska at the end of the summer of 1812. After visiting eastern New Brunswick, he rounded the Acadian peninsula and, with the heavy help of Indigenous guides and oarsmen, slowly ascended the Restigouche River. Plessis was aware of the Anglo-American border dispute and sent a scout ahead to ensure he wouldn’t be caught in the crossfire. The United States Congress had in fact declared war on Great Britain just two months earlier. Plessis continued on the Restigouche and then through the portage that led to the St. John River. A party of Canadiens came to meet him, shared provisions, and led him to the great river on land long inhabited by the Wulust’agooga’wiks (Maliseet).

Plessis recorded that 110 white families lived along the river, with farms stretching on both sides over a distance of about 50 kilometers (approximately 30 miles). In speaking with residents, the bishop found that many had refused to serve in the British colonial militia, expecting that at any time the area might become American. Of the people as a whole, he wrote,

The inhabitants of Madawaska, being composed of the dregs of Acadia and Canada, are a disunited, unruly people little likely to take up the good habits being impressed upon them by pastors. This rough parish has already tested the patience of many a priest. We have sometimes deprived it of such care, but it has become so numerous that we can no longer employ the same punishment.

Plessis was not exactly singling out the residents of the Valley. In 1815, he would describe many clusters of Acadian settlement in the Maritimes as hotbeds of heresy—and perhaps fairly. Missionary visits were sparse and Catholic parishes almost non-existent. This was a population largely living beyond the religious and government institutions deemed to be the mark of civilization. But Plessis and his successors would not despair and the growing population did, in subsequent decades, justify sustained attention from episcopal authorities in Quebec.

1832

It was not long after Plessis’s visit to the region that Joseph Bouchette, the surveyor general of Lower Canada since 1804, published a study of British North American geography. As his star rose, Bouchette received a grant of land in the Madawaska region from seigneur Alexander Fraser. In the late 1820s, he collected yet more data that enabled him, with some public support, to publish a Topographical Dictionary. Of the “fiefs and settlements” of Madawaska and Temiscouata, he explained:

This large portion of these extensive settlements has made some progress since Alex. Fraser . . . has established his residence at the village of Kent and Strathern, which is at the S. E. extremity of the portage on the borders of [Lake Temiscouata]. The inhabitants of this settlement are not numerous, and almost all of French extraction and Catholics. Near the Little Falls of the R[iver] St. John the Madawaska settlement begins and continues, by intervals, on each side of the R. St. John for about 25 miles; it consists of about 200 families of Acadians and Canadians. The cottages are for the most part neatly built, and both fields and gardens well cultivated. On the east side of the R. at the beginning of the settlement are a church and parsonage-house; there are also 2 corn-mills.

In the multivolume Topographical and Statistical Description of British North America, also published in 1832, Bouchette expanded:

The Madawaska settlement is chiefly composed of French Acadians . . . The land on both sides of the river here is exceedingly fertile, and well adapted to the growth of wheat, which is assiduously cultivated by the inhabitants, who, after grinding it into flour, send considerable quantities to the market of Frederickton, where it meets with a ready sale, at an abundantly remunerating price.

In a different volume, Bouchette discussed the importance of the Temiscouata portage in east-west communication and recent investments in a road through the region. Altogether, he saw the promise of the Upper St. John Valley; it was fertile and might support a double range of townships to welcome “the redundant population of the old French grants” and British immigrants. Such settlement would help secure communication between Quebec and Nova Scotia.

With this study, the moralizing tone of a Plessis gave way to a development ethos. Bouchette was calling imperial attention to a disputed region—selling it, even—whose growth and integration in the colonial system would help secure British North America as a whole. The Upper St. John was the essential keystone and its residents, the hope of the colonies.

1837-1839

The development of the lumber industry in the 1830s enhanced outside interest. An influx of American settlers and British efforts to assert jurisdiction over the region led to reprisals and inflamed public opinion on both sides. As national honor and commercial interest became the primary concerns of the boundary dispute, they erased the preoccupations of the local population. When the French-heritage residents of the region were mentioned at all, it was without regard for their interests, their culture, or their aspirations. Self-determination was not a consideration.

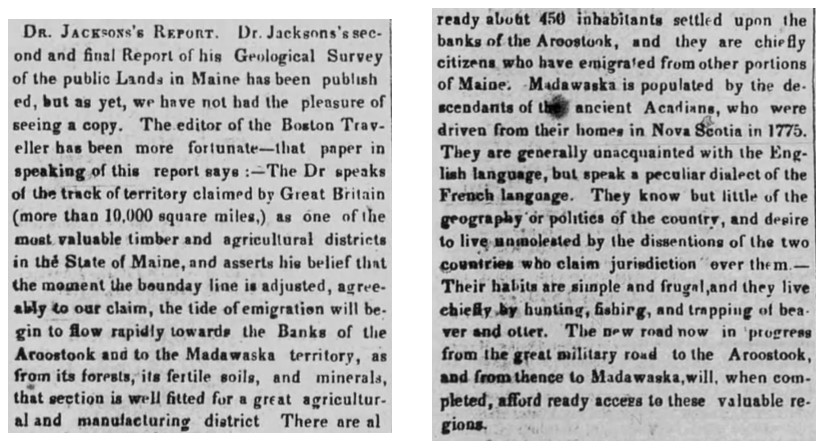

Admittedly, there were exceptional accounts. According to one report from the fall of 1837, Valley residents led by their Catholic priest had offered a pledge of loyalty to the lieutenant governor of New Brunswick. Residents were also mentioned by a Dr. Jackson, an American employed by the State of Maine. His perspective was quite similar to Bouchette’s but, as might be expected, he conceived of the Madawaska as the terminus of a natural north-south axis rather than as a link in an east-to-west chain of colonies. (See here for more on Jackson’s full report.)

The public erasure of the Madaskawayans may not have been a complete evil, however. The Aroostook War occurred at the end of the Jacksonian era and coincided with an unleashing of democratic zeal in the United States. Though we should not diminish the anti-Catholicism of the 1830s, radical Democrats like the Locofocos felt solidarity with all those who championed liberty and equality and thus easily extended their support to the Patriote “freedom fighters” of Lower Canada. Politics might prove to be a potent binding agent that would relegate cultural difference to a secondary plane. Had they taken advantage of the Aroostook War to pledge their support to the governor of Maine, the French-heritage population of the Upper St. John might also have earned cross-cultural support.

1842

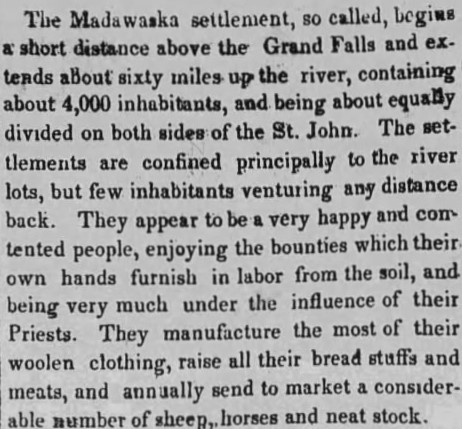

Officially, peace and a settlement of the border dispute came with the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. On the very day of its signing, the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier published the report of an American traveler who had seen the Madawaska for himself. The correspondent explained:

So much for being unruly and disobedient of clerical authority—though whether Bishop Joseph Signay in Quebec City agreed is another matter.

Yankee peddlers, the writer added, had begun to trickle in. But the Upper St. John remained resolutely French-speaking. The population, anchored by its farms and three Catholic churches, was now well rooted. Residents were generally illiterate and untouched by and uninterested in political events. “They seem to lead a sort of contented animal existence,” the piece stated, “leaving to the Priests the care of their souls, and giving themselves but little concernment about worldly affairs, so long as they have plenty to eat, and enough to wear. They usually marry early and there is no lack of children.”

Like Dr. Jackson, the writer, “Viator,” alluded to the road construction that promised to connect the region with centers downstate. Only then would it benefit from the (seemingly) unambiguous fruits of progress that were woven in the fabric of the American experiment.

1846-1847

Traveling from Quebec City later in the 1840s, American journalist Charles Lanman noted the small cluster of homes on Lake Temiscouata. Even at this date, the canoe was the only means of transportation in area. In Madawaska, there was little more than a blockhouse, essentially abandoned since the peace of 1842, and a yellow Catholic church with a red steeple. As for the people, Lanman, who undoubtedly saw himself as worldly, mixed the worst conclusions of Plessis and “Viator.” “[O]wing to their many misfortunes (I would speak in charity),” he explained,

the Acadians have degenerated into a more ignorant and miserable people than are the Canadian French, whom they closely resemble in their appearance and customs. They believe the people of Canada to be a nation of knaves, and the people of Canada know them to be a half savage community. Worshipping a miserable priesthood is their principal business; drinking and cheating their neighbours, their principal amusement. They live by tilling the soil; and are content, if they can barely make the provision of one year take them to the entrance of another. They are, at the same time, passionate lovers of money, and have brought the science of fleecing strangers to perfection . . . But, with all their ignorance, the Acadians are a happy people; but it is the happiness of a mere animal nature.

Lanman took the extraordinary step of attending Mass at Little Falls. Afterwards, local men raced horses; the winning steed, he quickly noted, belonged to the priest. As he continued in his journey, he found a sight that mirrored the St. Lawrence River valley of times prior: the farmhouses were organized along the river in a continuous village, with narrow plots stretching back from the water to allow equal access to this lifeline.[1]

In the Madawaska almost at the same time as Lanman was surveyor J. P. Bureau, who had been commissioned to report on the region by Denis-Benjamin Papineau, the commissioner of Crown Lands in Canada. The international boundary was now set in stone—in some places, literally. But the colonies of Canada and New Brunswick were still disputing control of the northern side of the border. It was to Bureau’s and Canadian officials’ advantage to highlight, for their own purposes, the value of the region:

From the first settlements on the Madawaska River, the sight is pleasant; the fields are open and the farm buildings well constructed. Into the river stretch points of land that produce great quantities of hay. The mountains are at some distance of the river and though they are elevated, the farmers have taken hold of them, easily clearing them and finding them productive. The inhabitants of this area are generally prosperous and live well . . .

[On the Little Iroquois River] there are many mills, including grist, lumber, carding, and fulling mills. Residents are almost all French Canadians, except for several Irish whose names I provide in my journal. At Little Falls, there are two villages, one to the east and the other to the west of the Madawaska, with the eastern being more considerable. There stands a military site, a blockhouse and dependencies on a rocky outcrop that offers a broad view of the St. John River. Little Falls is a handsome outpost where considerable business is conducted. It will only grow, for this is the only means of communication with the St. Lawrence River for the settlers of the St. John Valley, as much those on the Canadians side as those in Maine . . .

From the Madawaska River to the St. Francis River’s outlet, there are 179 settled lots and many more yet to be developed. These lots are all occupied by Canadians and Acadians. Generally, the farms are a mile and a half deep . . . On that section of the St. John River, the land appears to be of a high quality and the inhabitants live well. I have seen many settlements of great value, such that I regretted all the more that no road has yet been opened on that side of the river. Without roads, farmers travel by canoe or pirogue, which causes delays so considerable that their business suffers greatly and by that alone it is kept from advancing more quickly.

Back to Bouchette and the ethos of development we were. As the region might be joined to French-majority Lower Canada, the cultural character again receded to a secondary importance.

1857-1859

Much of the American public commentary of the middle part of the century drew from earlier sources and tended to repeat old tropes. In the era of nativist Know-Nothingism, any cluster of foreign-language people who belonged to the Catholic faith was bound to arouse suspicions. The Acadian French of Aroostook County were not spared. On May 18, 1857, the Hartford Courant, declared them “bigoted and ignorant, and completely under the control of their priests,” with “no idea of government.”

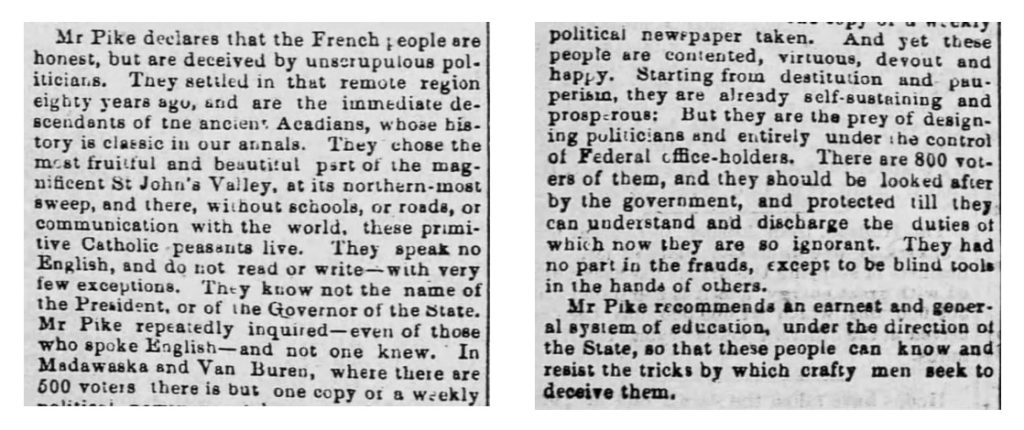

This last point was also the conclusion of a more sympathetic report that appeared in 1859. In an interesting twist, allegations of deception, election fraud, and corruption in the northern reaches of Maine reflected poorly on native-born politicians. But the corollary was still less favorable to the Madawaskayans. They had to be educated and properly folded into white American society:

That this population could be Americanized distinguishes it from many subaltern and racialized groups that were not afforded the same courtesy and that faced insurmountable marginalization. But this “courtesy” also entailed the gradual erasure of a culture—a mission that would reach its natural endpoint sixty years later with the Americanization bills of 1919.

* * * * *

Needless to say, the rationale for studying outsiders’ view of the Madawaska region is not to obscure the culture, concerns, and interests of French-heritage residents, nor is it to perpetuate or legitimize forms of nativism. Instead, it is a recognition that intercultural relations often had to occur on terms imposed by these outsiders, by virtue of the access to policymaking tools and economic levers that the latter enjoyed.

We should also run from the other extreme of thinking that the Madawaskayans were helpless pawns at the mercy of all-powerful WASPs. French-heritage people in the region formed communities and institutions, preserved their customs, sent their own to Fredericton and Augusta, and exerted their democratic will in more subtle ways. Residents who occupied what was first a disputed territory, then cultural borderland, and for much of this period an economic hinterland benefited from significant autonomy. It was this autonomy that disturbed Plessis in 1812, that raised concerns about political abuses nearly a half-century later, and that inspired Maine legislators to prefer the heavy hand of English-only public schooling from the 1890s onward.

The balance between local self-direction and outside interests changed over time. At times, residents experienced windows of opportunity when compromise, cultural acceptance, and autonomy were not only possible but desirable – perhaps due to common political and economic objectives. Greater historical attention to those windows may yield dividends in our own time.

Further Reading

For more outsiders’ perceptions of Valley residents and their significance, I recommend Beatrice Craig’s “Before Borderlands: Yankees, British, and the St John Valley French,” published in New England and the Maritime Provinces: Connections and Comparisons (2005).

[1] Lanman’s views were published shortly before Henry David Thoreau’s semi-famous travels in Lower Canada. Thoreau’s remarks about French-Canadian society in A Yankee in Canada offer parallels to “Yankee” perceptions of Valley residents in the same era. I have scrutinized Thoreau’s work in the American Review of Canadian Studies. See also shorter pieces on this blog and on Beyond Borders.

Leave a Reply