After drafting this post, I learned that James Myall (Parlez-Vous American) will be discussing disease and public health in connection with French-Canadian migrations on April 28. His talk will be carried on Zoom thanks to the Franco-American Centre at the University of Maine. Worth checking out I’m sure!

Last week, on HistoireEngagée.ca, I contributed, en français, an article that establishes parallels between an epidemic that struck Montreal in 1885 and our current struggle against the Coronavirus. Many journalists and historians have brought attention to the influenza epidemic of 1918-1919—with reason. But other moments in the history of disease merit attention and study in light of present circumstances, not least the events of 1885.

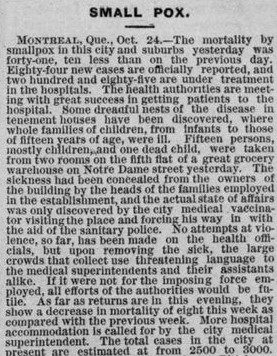

At that time, Montreal faced neither a different strain of the flu nor the scourge of the nineteenth century, cholera. It was smallpox—an awful plague that disfigured when it did not kill—that tore through the city. Some 3,000 Montrealers died; roughly the same number died in other parts of the Province of Quebec.[1]

Remarkably, by the 1880s, Western scientists and physicians (and yes, we have to use these terms loosely prior to the twentieth century) had known how to inoculate people against smallpox for over a century. Then, as now, the real issue was not the state of scientific knowledge, but what people chose to do with it. In Quebec, forcible quarantine and mandatory vaccination ran against the essential cohesion of the family unit, a desire to continue to observe cultural and religious celebrations, suspicion of state authority, and misinformation spread by quacks.

All of these factors help to explain resistance to the measures introduced by the city health board—as well as the ambulatory riot that exploded in downtown Montreal on September 28, 1885. Mayor Honoré Beaugrand, ill and in dire need of rest, left his home and personally marched a small battalion of special constables to disperse the angry mob. More confrontations erupted in months that followed and only in the spring of 1886 was the epidemic fully stanched.

The smallpox epidemic of 1885 is no longer public knowledge, or rather part of Quebeckers’ historical memory. We associate that year almost instinctively with the North-West Rebellion and Louis Riel’s execution, events which actually exacerbated tensions in Montreal and distracted city residents from the more urgent and existential issue of disease control.

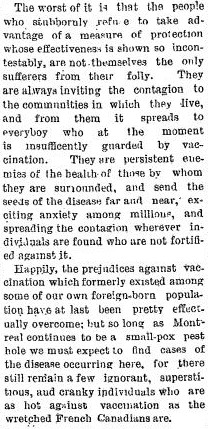

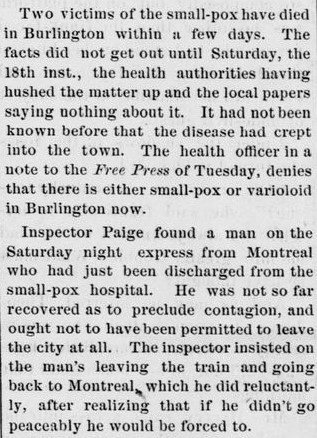

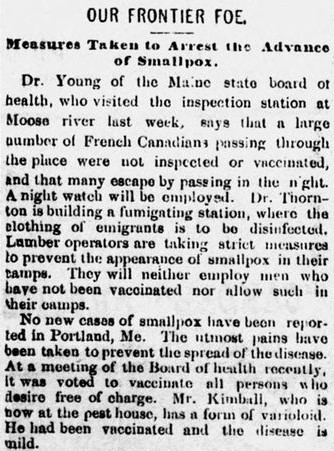

This also happened to be the height of the great demographic hemorrhage from Quebec. Annually thousands of French Canadians were leaving the province for the centers of New England and New York, raising fears that they would spread smallpox across the United States. (Paradoxically two English speakers had introduced the disease to Montreal from Chicago.) Ultimately, trains bound for the U.S. were closely scrutinized and American health authorities were able to prevent a major outbreak. The epidemic that was raging north of the border nevertheless contributed to stereotypes about French Canadians in the U.S.

I offer the following clippings from the English-language press as a small glimpse of the events and the public rhetoric surrounding them. As some articles suggest, the epidemic marked an important moment in state scrutiny of people crossing the international border.

In closing, I want to acknowledge the tremendous work of Mike Campbell and Jesse Martineau, whose French-Canadian Legacy Podcast featured a star-studded, three-part series on how the Franco-American community and its friends are adapting to public health guidelines. Mike and Jesse’s interviews are sometimes history-focused. Their podcast is also now making history. The episodes are well worth a listen.

Also in the world of podcasting, I recently had the opportunity to chat with Claire-Marie Brisson of the North American Francophone Podcast about my research and my upcoming talk at the University of Vermont. Actually, I may not be let across the border, but if there is a way of presenting remotely, I will let everyone know about it here and on social media.

[1] The essential works on the subject are Michael Bliss’s Plague: A Story of Smallpox in Montreal (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1991) and, on contemporary American events, Michael Willrich’s Pox: An American History (New York, Penguin, 2011).

Thank you very much for this. My great great grandparents Joseph Chauvin and Mary Ann McCarthy left Montreal early in 1886 and this gives me something to consider. Joseph’s siblings and parents all went to Malone New York but Joseph and Mary Ann went to Boston and I believe they left Montreal earlier than the rest of the family. Trying to figure out when they left and why. I’ll need to read up on this

Thank you for commenting and sharing your story, Kathy. Sounds like a fascinating journey. I’m always seeking new information on migrations to upstate New York. Would love to learn more about your Malone connections! Good luck in your research!

Interesting, but what struck me is the contrast between the ignorance of the Québécois back then and now. People then were ignorant not by choice but because the Catholic Church kept them ignorant. And the clergy did this because of the Gentlemen’s Agreement they made with the British Colonial regime, since it’s a lot easier to keep ignorant people under your thumb than if they were educated.

Thank you for commenting, Michèle. That was certainly Henry David Thoreau’s view when he visited in 1850! The Church’s role during epidemics could be ambivalent. But it wasn’t just a matter of education. Catholic clergy wanted people to continue to participate in the life of their parishes even amid rampant disease; there was also a fear of “big government” – apparently a Protestant doctrine that would extend Anglo-Saxon power. But by September 1885, the Diocese of Montreal was on board with public vaccination campaigns and weighed on the faithful to comply with local public health ordinances.

Pingback: This week’s crème de la crème — April 11, 2020 | Genealogy à la carte

Are you familiar with the National Film Board documentary , “ Outbreak: Anatomy of a Plague “ ?

Thank you for mentioning it – I wasn’t aware of it, but now I’m intrigued and will check it out! Seeing Michael Bliss in the credits is incentive enough.