Marie Mainville’s family may have had some notoriety in Saint-Ours, the Richelieu parish where she grew up. Her father, baptized Jean Baptiste but known in adult life as Charles, had acquired minor infamy for his role in the Continental Army’s occupation of Quebec. He served as a scout for the insurgents and British authorities imprisoned him on three different occasions. After the war, perhaps persona non grata, rather than returning to his home parish in the Bas-du-fleuve, he settled in Saint-Ours. He married and became a cultivateur, a landowning farmer.

Though raised in the shadow of a strong-willed and possibly well-known father, Marie Mainville likely had a conventional childhood by the standards of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In 1811, at age 19, she married Pierre Sanschagrin, whose family resided in La Présentation. Oddly, the couple married in the groom’s home parish rather than the bride’s, though it may be that Marie was living with relatives or working as a servant in La Présentation. Stranger still, we find in the wedding record an unusual phrase not used in other marriages performed in that time. The matrimonial blessing was granted “after having heard the witnesses who attested to the freedom (liberté) of the said Pierre Sanschagrin.” Could it be freedom from a prior marriage contract? We may not know until the Sanschagrin-Mainville contract, signed two days before their wedding, becomes available.

Marie gave birth to Pierre fils a year later and then to Louis in 1814. Pierre had purchased a parcel of land along the Salvail stream in the seigneurie of Saint-Hyacinthe in 1810; the couple appear to have been in effective possession of another plot, located nearby, from March 1814 on. Between the two plots, they sat on 127 acres. On paper, at least (and that is all that remains), they could envision a prosperous future.

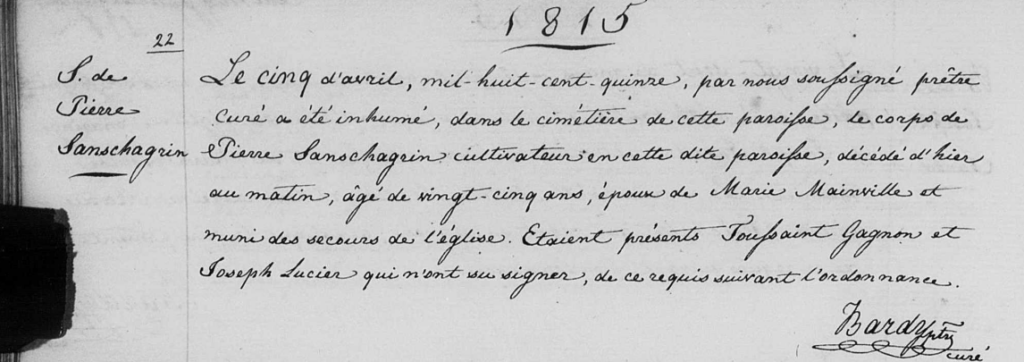

Well, now for the plot twist that eventually produced this writer and makes this blog post possible: Pierre Sanschagrin père, Marie’s husband, died aged only 25 in the spring of 1815. Farm accident, drowning, fatal ailment—the cause is lost to history. One is simply struck by the abridged timeline that may have felt like a bad dream to the family. He died on the morning of April 4; he was buried the next day.

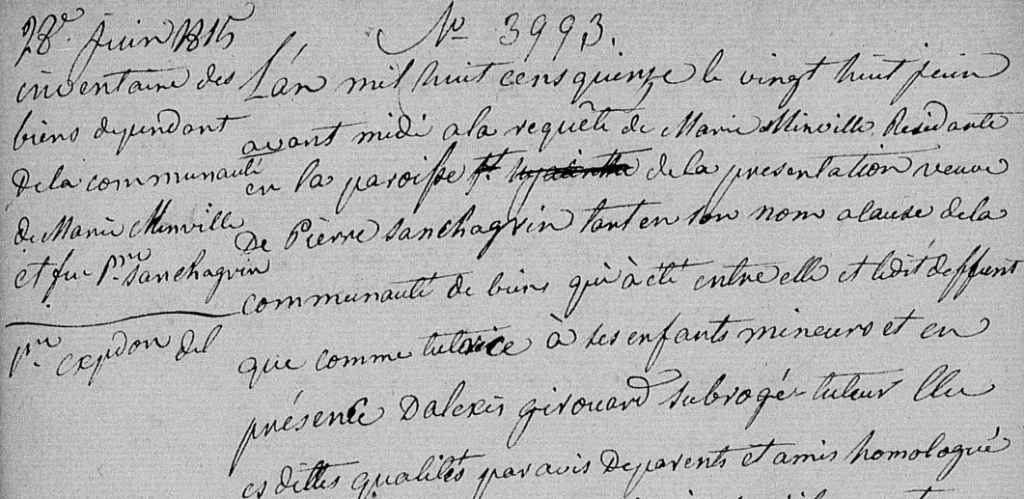

Whatever the exact terms of the marriage contract, the couple had formed a marriage community in a legal sense—and that community of goods and interests had now dissolved. As Gilles Paquet and Jean-Pierre Wallot note, by law, if no postmortem inventory was undertaken within three months of a spouse’s death, the survivor personally assumed the responsibilities and financial interests of the marriage community. A legal inventory, on the other hand, could make for a clean slate. It might be requested by the surviving spouse, the executor or executrix of the testament, or the children’s appointed tutor; it served to protect all those who might have an interest or a stake in the property of the now-dissolved marriage community, including the immediate family, legatees, and creditors. It was all the more important in families where the deceased had not left a final testament. Such was the case of Pierre Sanschagrin and his family.

At the end of June, 1815, notary Louis Picard, two respected local residents, and the children’s appointed surrogate guardian assembled at the Sanschagrin farm. With the widow, they identified every item in the household and in the barn and assigned a value. The value of all of the belongings would be weighed against debts, obligations, and the needs of the children. Without a testament, Marie might not have a claim to the wealth of the community beyond what she brought into the marriage, unless there were clear stipulations in the marriage contract.

In fact, the full inventory was put to auction on the same day—and Marie was one of the bidders. She purchased a number of goods from her own dissolved marriage. In the end, between the assets she held outright and her purchases, she simply owed seven and a half livres.

We might fear that Marie—a 23-year-old widow with two toddlers—was left on the brink of destitution, but, two weeks after the inventory, she provided £300 and closed the sale of the plot that her family had occupied since 1814. In October, she signed a new wedding contract that made little reference to her possessions and remarried. Her new husband, a local farmer named Jean Lacroix, had served with the militia in the recently ended war between Britain and the United States. We may wonder what Marie’s father, old Charles Mainville, thought of the young man who had fought alongside the British. Either way, the saga of the first marriage continued. In March 1816, almost a year after Pierre Sanschagrin’s death, the parties again gathered to divide the wealth of the marriage between the widow on one hand and her children on the other.

The notary tallied proceeds from the prior year’s auction, money owed to the Sanschagrins, and the value of the last harvest. He subtracted the household’s own debts, fees for the notary and arbiters, and the cost of bringing in the harvest. Marie claimed her dowry and another small sum to which she was legally entitled, leaving a grand total of 1,256 livres to be divided. The mother would get half and the children split the other half. This also occurred with one of the parcels of land. Marie retained the other plot, though it entailed financial compensation. When all was said and done, Pierre fils and Louis owed their mother approximately 200 livres. They would settle the account twenty-four years later.

The second marriage lasted: Jean would pass away forty years later, all but one of their nine children having reached their majorité (legal adulthood) by then. It remains that Pierre Sanschagrin’s death upended the course of Marie’s life. She left the piece of land along the Salvail stream and we do not know why. Perhaps it did not suffice for the support of a growing family. Over the course of twenty years, we find Marie and Jean Lacroix in Saint-Hyacinthe, in Saint-Michel-d’Yamaska, in Saint-Damase, and eventually in Saint-Césaire, a poor parish on the Eastern Townships’ doorstep. They even spent years—five, maybe more—in the midst of English-speaking Protestants in Brome Township. The family’s itinerant ways would persist with their children, most of whom would live and die in the United States.

The following shows the inventory of physical goods in Pierre and Marie’s possession as listed and valued in June 1815. It is reorganized here to provide greater coherence to the items and their purpose. It does not include Marie’s clothing or her children’s, which might be considered inalienable property, or other personal belongings with little to no monetary value. Other goods that Marie brought into the marriage may have been set apart by the marriage contract, perhaps as a preciput, thus escaping the inventory. It remains nonetheless that, while a fairly conventional household, the Sanschagrins did not have an inordinate amount of household or agricultural goods and that everything had a clear function. The values are given in livres françaises (#), similar to British pounds, and sols or sous (s), with 20 sols to a livre. The most valuable items were the two horses and the cast-iron stove.

Caveat lector: I have included question marks to show undecipherable words. I have translated the inventory and used modern terminology, but, in some cases, lacking specifics and navigating archaic words and spellings, we are at the mercy of historical ambiguity. For instance, the notary lists “une canne.” Today, we would translate this as a walking cane. But because it immediately precedes the chickens, it is likely a non-standard spelling of “cane,” a female duck. Still, most items appearing below—a valuable snapshot of the material life of early nineteenth-century French-Canadian farmers—are offered here with a strong degree of certainty.

Kitchen

- Seven earthenware plates, #1

- Seven pie pans, two other pans, a tureen, a soupiere, a pot, three bowls, and a saucer, #1

- Thirteen bottles, #2

- One small cupboard, #2

- A bucket and a pan, 10s

- A utensil box, six spoons, three forks, #1, 10s

- A cooking pot, #3

- A small cooking pot, 15s

- A pair of andirons, #6

- A stand, #2

- A large cooking pot, #6

Other household items

- Two augers or spins and a stitching awl, 2s

- An iron bucket, #1, 10s

- A clothes iron, #1

- A vat, #2

- A wash basin, 10s

- A box and card(?), 15s

- A straw mattress or bench cover, #2

- A pair of ropes, 15s

- A wooden box, possibly a bread bin, #1, 10s

- Five horseshoes, a hammer, and broken fire tongs, #1

- A shovel for coals, 10s

- An ax or hatchet, #2

- A “ferrée,” #3

- A grate, #1

- Two spoon molds, one being a button mold, and a spoon for pots, #9

- Three sacks, #1, 10s

- Two jugs, 10s

- Two grease pots, 15s

- A hamper, with its contents (unspecified), and a basket, 10s

- A chamber pot, 15s

- A hamper and a spool, 10s

- Two old hats and shoes, 10s

- A cast-iron stove, #60

Farm implements and accessories

- A collar harness with reins, #10

- Two collars and a pair of …(?), #2

- An iron brush for animals, 15s

- Twelve old horseshoes, #2

- Miscellaneous iron, 10s

- Two cruppers with chains and ties, #1, 10s

- Red leather, #1

- A salting tub and a half-bushel cask or container, #3

- A barrel, 10s

- A robe or blanket (likely for horses) and blinders, #12

- Twenty-five iron harrow pins, #6

- Miscellaneous iron and a scythe, #3

- Two windows, a shovel, and a paddle, 10s

- A set of planks …(?), #1

- Ash, 4s

- Bran, 10s

- Two …(?) and a pair of blades, #3

- Three sickles, 10s

- Wood from a loom, #3

- A sifting cloth, #2

- Calf leather, 4s

- A full plow, #15

- A table(?), 10s

- A sled on irons, #6

- An old pair of wheels, #1, 10s

- A small cart with wheels, #24

- A large cart, #6

- A new saddle(?), #18

The deceased’s clothing

- Two pieces of cloth, #1, 10s

- A box and razors, 10s

- Two shirts of fine cloth, #3

- Three vests and a silk handkerchief, #6

- A hat, #2

- Two wool tuques, #2

- Two pairs of corduroy pants, #6

- Two waistcoats or jackets, likely linen (“drap”), #3

- Two waistcoats or jackets, likely wool, 15s

- A pair of breeches, likely linen, and another, likely wool, #2

- A pair of breeches, likely linen, #3

- A linen overcoat and a red waistcoat or jacket, #10

- Three flannel shirts, #3

- A pair of breeches, #2

- A wool overcoat and a piece of cloth, #3

- Two pairs of socks, one pair of …(?), and a pair of gloves, #1, 10s

- A hamper, 15s

- Thread, 6s

- Two hats(?), 10s

Animals

- A duck, 5s

- Twelve chickens and four cockerels, #3

- A sow, #22, 10s

- Two piglets, #3

- A black horse, #135

- A …(?) horse, #109, 10s

- A red cow, #81

- A heifer, #45

- A bull, #18

- Another bull, #9

Marie stated that she had 12 livres (cash). She further declared to have sown nearly twelve bushels of wheat, six bushels of oats, five and a half bushels of peas, about 3 bushels of potatoes, a half-bushel of barley, and a half-bushel of flax in the spring.

For more on the history of Quebec homes:

- Hélène Bédard, Maisons et églises du Québec: XVIIe, XVIIIe, XIXe siècles

- Jean-Claude Dupont, “L’habitation chez les francophones au Canada”

- Fiches architecturales, MRC d’Acton

- La maison néoclassique Québécoise, MRC des Chenaux

- Maisons ancestrales, Société d’histoire de Neuville

For more on the Lacroix family, see A French-Canadian Journey: Bellechasse to Sweetsburg.

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - January 4, 2025 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte

Is there a reference for your comment, “It does not include Marie’s clothing or her children’s, which might be considered inalienable property, or other personal belongings with little to no monetary value.”

Hi Pete. Yes: Gilles Paquet et Jean-Pierre Wallot (1976) state, “L’inventaire recense les biens personnels des époux, y compris les habits, le linge et les hardes du survivant, à l’exception toutefois d’un habillement complet à son usage, de ses pierreries et diamants, ainsi que du linge et des hardes des enfants.” So, the children’s clothing was excluded, as was a full outfit for the surviving spouse, but, since Marie’s clothing isn’t mentioned at all, it may be that, by tacit agreement, the legal convention would extend to all of her clothing. Then again, she may not have had much more than a full outfit. The contract for her second marriage (1815) states that after the inventory, “the said survivor [will claim] their bed . . . and trunk with cloth for the body [linges de corps], clothes, and outfits for their own use” (my translation).