Beginning in 1858, an American correspondent signing “S. M.” shared his impressions of life in Lower Canada for readers back home in Vermont. “Having lived many years in the midst of the French population, and being familiar with their manners, customs and language,” the author explained, “I propose to drop you a line now and then from this part of the world.”

His series of letters—at least fourteen over the course of two years—addressed various facets of life in Canada, with particular attention to history, rural customs and practices, religion, and political developments. In retrospect, there is a noticeable arc to the letters. They seemed to become more sympathetic and admiring over time, to the point of flirting with the risk of depicting this as a near-utopian pastoral society—which must be put in the context of mass outmigration. But, generally, the author weighed fairly the relative benefits of certain farm practices on the two sides of the border.

Both this week’s post and the next one are direct excerpts of the “Canadian Breezes” series. This post is based on letters published on May 12 and June 23, 1860. It builds on prior pieces on the challenges of farm life in earlier decades and French-Canadian cultural practices.

* * *

Almost the first work done in the spring is putting up the fences by the side of the road—for they are thrown down when the first snows fall, so the wind may have a clean sweep—and repairing old fences and making new ones about the farm. Their fences are made of cedar, and they are very neat about them. Their rails are ten French feet—about twelve English in length; they are laid up perfectly straight, and supported at each end by large posts driven firmly into the ground, which are held together by a wooden pin. I never saw any fence just like it in Vermont, nor did I ever see a Yankee who could make one like it. Standing in any such place and looking widthwise (there is no such word, but there ought to be) of the farms, you can see nothing but fences, fences for miles away.[1]

People living on the comparatively poor soil of New England would be surprised to see the great piles of manure lying about the barns—I have seen the accumulation of years there; but they are beginning to learn that it pays to draw it back upon the land. I have known of many farmers, living in the less fertile sections, being obliged to sell out their farms, for they had neglected during so many years to manure them, that they could not get a living on them. Scotch and Irish farmers bought them ought [sic: out], and they are now rich and the farms productive. The farmer generally runs a fence through the middle of his farm; cultivating for two or three years one-half and pasturing the other; then pasturing one-half and cultivating the other. His pasture is always poor, for he never seeds it, the only green things in it are Canada thistles and barn grass.[2]

He does most of his plowing in the fall, and is very nice about it; the land is so level and smooth that he can cut a furrow a mile long without breaking it. A side-hill plow he never saw.[3] The entire country—mowing, pasture and plow-land—lies in beds from five to eight feet wide, which are formed by turning three or four furrows in on either side of the narrow strip. There is thus formed a little ditch between the beds, into which the water falls and is carried off. Of course nothing grows in the low places, so nearly one-eighth of the land produces nothing.

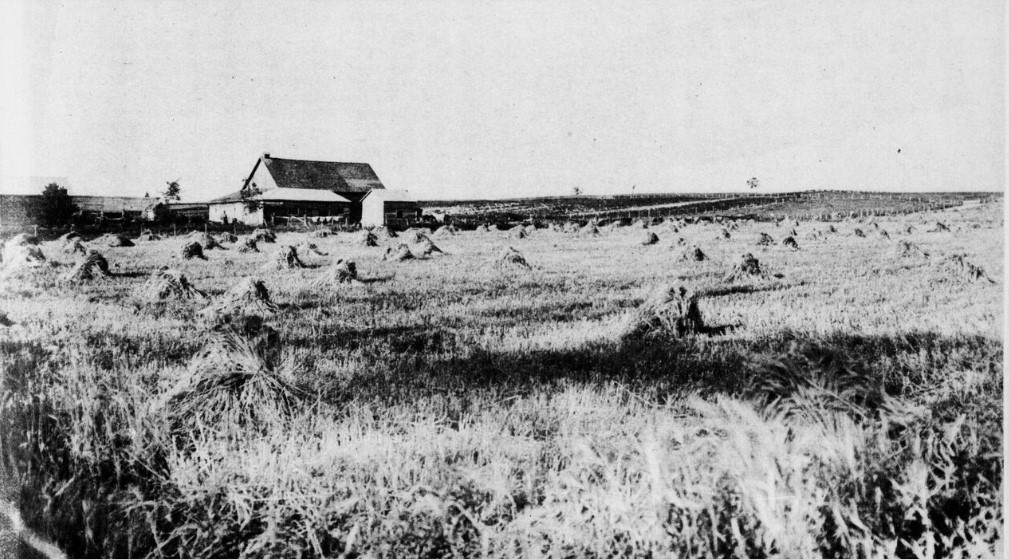

They do not often begin to do much on their farms earlier than the first of May. Oats and barley they sow as soon as the land is dry enough, but they do not get their wheat into the ground until the first and second weeks in June. You will see that in the busy season of the year the whole household go into the fields to work; the men are plowing, repairing fences, cleaning up ditches and sowing grain; the women follow, from morning till night, the harrow.[4] They use a small harrow, having many teeth, with handles fixed to it by which to manage it. They sometimes plant a little corn, but so thick that it does not amount to much—frequently mixing it in with potatoes, making a swamp of it. At this season of the year they are very busy in the new ranges making (as we say in French) land. They make clean work of clearing land, taking out every tree, root, and branch. They do not work for years among the stumps, waiting for the time to rot them away. We can get land cleared in this way for from six to twelve dollars an acre. The most of the French country is so clayey that a dry time at this season of the year is very injurious; for the land becomes so hard that it cannot be plowed or harrowed, and I have seen the whole agricultural operations of a great section of the country at a stand still for many days. […]

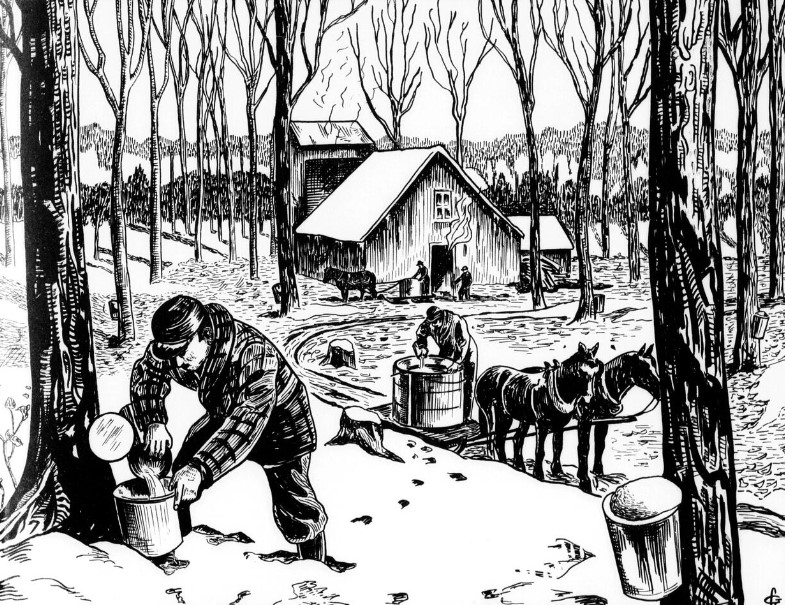

Their dairies are very poor affairs; they have more horses than cows and tend them better than they do the cows. Many of them churn by stirring the cream with the hand in a pail. A poorer lot of butter could not be found than is offered for sale on the French markets. The Canadian sheep bear a coarse long wool which makes a very durable cloth. The women shear the sheep, and manufacture their own cloth; the spinning and weaving of which gives employment to them during many weeks in the year. The wool is spun on a flax wheel (I believe that is the English of it; I mean a small wheel turned by the foot,) in the way flax is spun. They sometimes have spinning bees, and I have seen twelve or fifteen all buzzing away in the same room. Such a sight calls to mind the olden times.

A few years ago they used very little cotton, raising flax and making linen enough for domestic use. Many of the more wealthy farmers have such quantities of linen that they wash only twice in the year—in the spring and fall. The women perform the whole labor on the flax from the time the seed is sown until the linen is ready for use. You may frequently see a half-dozen women at work together, breaking the flax; this is done in the spring and fall, and in the open air. They dig a narrow trench in the ground, set up boards on each side about four feet high, and lay poles across the top. A fire is kindled in the trench, the flax spread on the poles, and in a short time it becomes very dry. Here, in the smoke and wind and dust, they work several days each year. How many New England farmers’ wives and daughters would do it? It helps to preserve to them healthy and vigorous bodies.

As the Canadian farmer plants very little, he has not much hoeing to do; and the long days in June, so painfully spent, by the Vermont farmer, in keeping the weeds down amongst his corn and potatoes, are passed in comparative ease. In fact not half of them ever saw a regular hoe; they have a great heavy, clumsy thing, resembling a pick quite as much as a hoe, which they call a pioch[e]. When their sowing is done they have not much to do until haying, and their time is passed in happy inactivity. As the season for making hay approaches, you will see as you pass along the road the manufacture of forks begin. They are made of a little staddle, of the required size, by leaving two prongs eighteen or twenty inches long, which serve as tines; and as they seldom find them having the proper crook, they give them this by fastening them for some days into the rail fence. The numbers you see by the way-side attest that they are in general use. The Canadians prefer them to any others, and as they load hay on to their carts, are more convenient than the most finished forks would be.

It is curious to notice how a whole population do the same thing in just the same way, and how differently they do it from another race of men. It is a distinctive mark of character, and this simple fact of the Canadian putting hay upon his cart, compared with the Yankee putting it upon his, would enable a philosopher to tell what the two races of men were, and wherein they differed, just as surely as he could tell to what an extent those who built the Pyramids must have been civilized. The Canadian has his hay raked in small piles of twelve to fifteen pounds, and under them he neatly thrusts his long-tined wood fork and carefully lays them upon the load. He could not sweat at it if he should try—it plainly shows that he takes the world easily. See now the blustering [Y]ankee getting in hay—he has it in great piles over the field, and stabs the fork deeply into them, taking up as much as he can possibly lift. Great drops of sweat come rolling down his flushed visage—that he goes whistling through the world by steam. The season of cutting hay commences here from the 20th to the last of July.

[1] In the wake of the snowmelt, the next task awaiting the family would be a field walk to remove rocks and stones—which would otherwise hamper the plowing—exposed since the fall.

[2] This was a recurrent comment of British, Irish, and American observers of French-Canadian agriculture in the nineteenth century. The typical Canadian farm seemed to be reliant on field rotation and less deliberate in its use of manure. Pasturing only went so far due to their typically small herds.

[3] A hillside plow, a nineteenth-century invention, included a mechanism that could flip its angle from left to right and back to ease the process of turning over soil. A farmer making passes in opposite directions would not have to turn soil over against the angle of the hill.

[4] An implement that breaks up the soil.

Because I’m writing about a farming community circa 1860, this is like Christmas to me. What a great resource these letters are! How do I get my hands on them?

Joan: I’m thrilled to hear it! They were published by the Vermont Journal (Windsor, Vt.), which is very conveniently accessible on Newspapers.com. As far as I can tell, the first letter appeared on June 10, 1858. Only four had appeared by September 1859, but then the author really committed to the endeavor and his letters were published roughly at a rate of one per month until August 25, 1860 (the last I could find). You may be able to find them simply by searching for “Canadian Breezes” or “Breezes from Canada.” As noted, they covered all sorts of non-agricultural topics. Most of the information on farm life appears either in this blog post or in the next.

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - October 21, 2023 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte