We might call it a consensus. Whereas most works of Franco-American history focus on the period between the U.S. Civil War and the Great Depression, scholars would generally agree that the great hemorrhage, la grande saignée, began around 1840. Amid the economic and political turbulence that followed the Canadian Rebellions of 1837-1838, French Canadians settled in the United States in ever-rising numbers. Some lived abroad only temporarily, but the collective phenomenon was permanent. With notable exceptions, many Little Canadas date from the 1840s and 1850s.

Prior to 1840… a void. We might call these years the “dark ages” of French-Canadian migrations. As with the actual Dark Ages, the problem lies in the availability of documentation. The sparsity of research on the pre-Rebellion era reflects the sparsity of resources—or so it seems. We might count on one or two fingers the number of researchers who have plumbed records to properly trace cross-border migrations in the early part of the nineteenth century.

To be sure, there are documents. However, pre-1850 Canadian census records are notoriously imprecise and incomplete. Until that time, American enumerators did not record all members of a family, only the head of household, nor did their worksheets provide an opportunity to list places of origin. It is therefore immensely difficult to follow specific families from place to place. To such methodological barriers that are painfully familiar to genealogists, we might add the “John King” problem. If one sees a person named John King in early census records, there is no telling, from the document, whether this is a Protestant Yankee or a Jean Baptiste Roy whose name was anglicized. At least, from 1850, a string of typical French names (which might appear as Angeline, Antwine, Battis, Celest, Mary Ann, Mitchell, etc.) in a certain household can provide guidance, suggesting that King may in fact have been Roy—or Cross actually Lacroix.

We also have mounting qualitative evidence. I expose some of these contemporary sources in my article, “Prelude to the ‘Great Hemorrhage’: French Canadians in the United States, 1775-1840,” published in the American Review of Canadian Studies (2021). Travel chronicles, newspapers, correspondence, memoirs, and other documents shed light in what is otherwise a time of obscurity. The earliest source that speaks of migration to the United States as a collective movement among French Canadians dates from 1826—though earlier sources that say as much may yet be (re)discovered. This doesn’t include what may be the single most significant resource for pre-1840 migrations: the sacramental records (births, marriages, and burials) of the Catholic Church in Lower Canada.

I have previously brought attention to these records, albeit in passing, on this blog. They provide valuable information about the resumption of ties between Revolutionary-era refugees along Lake Champlain and their ancestral homeland in the 1780s and 1790s. The records of the Chambly and L’Acadie parishes, on the Upper Richelieu River, are a wealth of information on cross-border kinship ties. In January 1799, for instance, Revolutionary families traveled in numbers to L’Acadie: Prisque Asselin and his wife Louise Boileau, residing on the shores of Lake Champlain, came to have a child, Prisque fils, baptized; Anastasie Gosselin, niece of the famed Major Clément Gosselin, and Etienne Trahan also brought a child be baptized; and Pierre Bleau married Théotiste Paulint, daughter of Captain Antoine Paulint.

New finds in archival collections led me to scour parish records farther west along the forty-fifth parallel. The Kent-Delord Collection at SUNY–Plattsburgh holds significant materials pertaining to French-Canadian soldiers of the War of Independence. The papers of local big wig Benjamin Mooers in particular provide insight about the porous international boundary along Clinton and Franklin counties in upstate New York. A letter from Nathaniel H. Tredwell dated January 3, 1821 suggests that French Canadians were likely to be the primary purchasers and settlers of Tredwell’s and Mooers’s holdings. As immigrants to Canada had “land given to them[,] the only settler[s] within our Reach at present are the Canadians from the Siegnories [sic] below, as they are suited with the land we have to dispose of.”

Those holdings may have been just across the border, for a letter from John Hawkins, also dated 1821, hints at American speculation in Canadian lands in the Hinchinbrooke area, near present-day Huntingdon, Quebec. But, with the border meaning so little, this may be a moot point. French Canadians were moving outwardly from the St. Lawrence River in this period; they began to settle the townships west of the Richelieu River and spilled over the border.

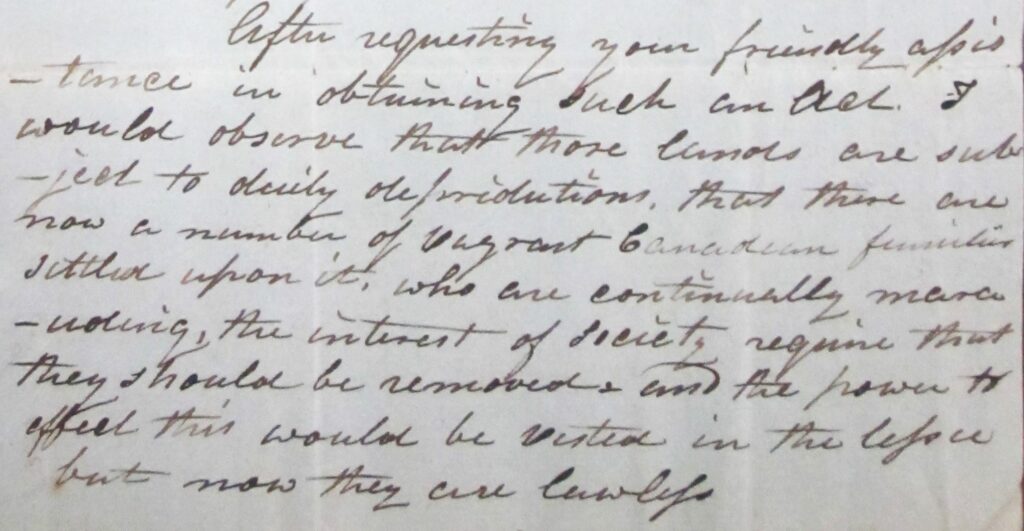

Three weeks after Tredwell’s missive, Mooers received a request from another correspondent. The writer sought to secure a long-term lease on the military ground in Fort Covington, located on the Little Salmon River only three miles from the St. Lawrence. The land was then in the hands of the St. Regis Reservation. An extended lease would require an act of the legislature, which Mooers might facilitate. He went on:

After requesting your friendly assistance in obtaining such an Act, I would observe that those lands are subject to daily depridations [sic], that there are now a number of vagrant Canadian families settled upon it, who are continually marauding, the interest of society require that they should be removed and the power to affect [sic] this would be vested in the lessee but now they are lawless.

The idea of “marauding” French Canadians—thieving and plundering their way through northern Franklin County—may seem fanciful or hopelessly tinted with prejudice. The author may have deliberately exaggerated to communicate urgency. There are, however, deeper truths hidden within. Families were beginning to look beyond the old seigneuries. On both sides of the border, squatting and legal land titles were becoming pressing issues. According to one antiquarian work, the seigneurie of Beauharnois, south of Montreal, had a population of 2,205 in 1820, about half being French-Canadian. None of the farming families in the seigneurie had officially received title to their lands.

Not coincidentally, Fort Covington had once been known as French Mills. From 1796 into the new century, while Vermonters were pouring into the Chateaugay, New York, area, French Canadians were moving up the Little Salmon and St. Regis rivers into what is present-day Hogansburg. In the short term, these inroads were not intended as a large-scale colonization scheme. J. H. French’s Gazetteer of the State of New York states that prior to settlement in the Bombay, New York, area, “most of the valuable timber [unquestionably oak, but possibly pine as well] had been stolen by parties from Canada.” The only commercial products of note in these frontier regions were potash and lumber, which would explain the building of mills near the border at the turn of the century. Though Benjamin Mooers and his network were concerned about squatting, the “marauding” alluded to likely referred to the pillage of lumber that significantly decreased land values.

The extractive phase of French-Canadian penetration in northern Franklin County ended—so far as the written record suggests—in 1804. In the 1820s, a different phase was under way. But it seems it was the influx of Irish Catholics, nearly all arriving via Quebec City and Montreal, at that time, that drew the attention of religious authorities in Lower Canada. In 1830, Father James Moore was sent as a missionary to Huntingdon County, which stretched south of the seigneuries, between the St. Lawrence River and the Lacolle area. Moore’s record of baptisms, marriages, and burials tells of a settlement phase on both sides of the international border. His missionary work primarily served a growing Irish population that lived on the margins of Lower Canadian society—and in Fort Covington, Malone, and Bombay, New York. No less, there were French Canadians both in Huntingdon County and beyond. In the summer of 1831, a farming couple appeared before Moore to have their daughter christened. Louis “Derusselle” and Marie Catherine Lesage were residents of Chateaugay, New York. By their very presence, these cultural pioneers announced the larger migration to come.

Moore’s missionary circuit stretched well beyond Huntingdon County. He never indicated in his sacramental registry precisely where he performed Catholic rites, but the places of residence of the people he met attest to lengthy travels. For several weeks, in the summer of 1830, he visited the Upper Richelieu region and Missisquoi County. French Canadians had entered the Eastern Townships and were settling to the east of Lake Champlain. In light of the number of U.S. residents that appear in the records, it is very likely that Moore crossed the border to visit them—and so he met people named Cloutier, Côté, Berger, and Lajoie. In 1831, his work seems to have taken him as far as Granby, Quebec, and Derby, Vermont, where he baptized a child of Michel Sinotte and Françoise Forcier. The couple had married in Saint-Hyacinthe and would eventually return.

Cross-border migration by French Canadians appears to have been more substantial, through the 1830s, along the Richelieu and into Vermont than through Huntingdon County. But a major event was soon to have an impact on Huntingdon and lead Canadians into Franklin County. Although often lumped as one, the Rebellions of 1837 and 1838 erupted in different ways, in different areas, and had distinct consequences. The colonial government’s response to the 1837 uprising, which erupted along the Richelieu and north of Montreal, was very mild by nineteenth-century standards. In the fall of 1838, a new insurrection, organized in part by exiles on American soil, with American support, and affecting the border region led to much more forceful repression and intimidation. Huntingdon County felt that dearly.

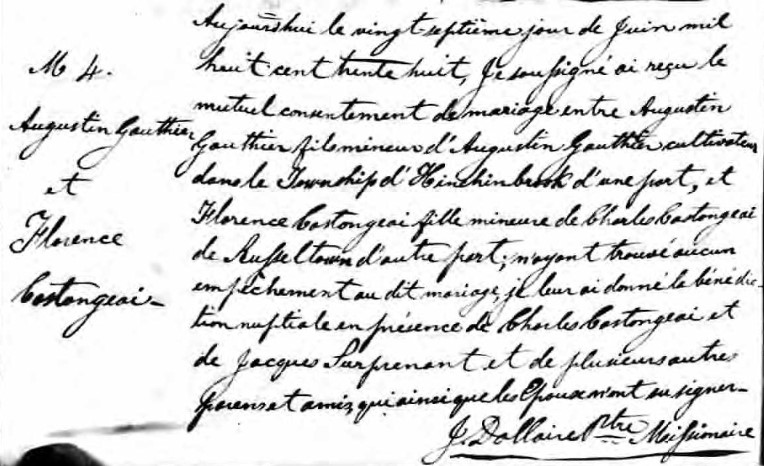

It is difficult to distinguish political refugees from economic migrants; Lower Canada experienced hard times in commerce as in agriculture and, when combined with population pressures, the economic situation was enough to push young families abroad. We know little of the Lemieux, Ouellet, and Girard families that Moore met in October 1838 likely in Chateaugay, New York, where they all resided, nor do we know exactly what decided them on a foreign sojourn. By 1839, however, with the higher number of Franklin County French Canadians in missionary records, it would strain credulity to suggest some of the men were not in fact refugees. Names include Charles Cyr, Augustin Gauthier, Simon Boudria, Jean Baptiste Lamontagne, Joseph Beaudin, and Jean Baptiste Landry. Women, too, were active participants in the paramilitary Frères Chasseurs, and often administered the organization’s oath, but they seldom faced arrest or legal reprisals.

The number of baptisms for Franklin County residents was again higher in 1840. After repeated false starts, a “migratory beachhead” was thus established west of Clinton County, New York. At the time of the census of 1840, the federal enumerator met families named Duquet, Primeau, Nadeau, Arpin, and Bachand in Chateaugay. His counterpart in Fort Covington recorded the Denis, Laflèche, Chevalier, Lafleur, and Larocque families among others. This, of course, is not counting the many “John Kings” who lie perhaps forever hidden.

In Franklin County, New York, there is something to the idea that Lower Canada’s demographic hemorrhage began circa 1840 (that is, as something more than a trickle). But we should recall that decennial census returns and missionary records can easily miss seasonal and temporary migrations. Prior to the Rebellions, prospective migrants were aware of cross-border commerce and may have taken part in it themselves. They accessed information about foreign opportunities through kin, friends, and neighbors—perhaps from an uncle who had “marauded” a generation earlier. They developed a cross-border mental geography before even planting roots in the United States. Much more may be done to recover the economic, political, and intellectual lives of the people who, in these “dark ages,” laid the basis for the dramatic outmigration of nearly one million French Canadians.

A Note on Sources

Nineteenth-century antiquarian works provide valuable context and sometimes include orally-transmitted histories not available elsewhere. Among these are: J. H. French, Gazetteer of the State of New York […] (1860); John Talbot Smith, A History of the Diocese of Ogdensburg (1885); and Robert Sellar, The History of the County of Huntingdon and of the Seigniories of Chateaugay [sic] and Beauharnois from Their First Settlement to the Year 1838 (1888). Sellar’s work is reminiscent of Catherine Matilda Day’s history of the Eastern Townships in that it tends to invisibilize the French-Canadian and Catholic presence. American works at times seem more interested in chronicling the arrival of the Canadiens in this early period of settlement. A more recent work penned by scholars, The Encyclopedia of New York State, edited by Peter Eisenstadt (2005), also proves helpful, though many entries rest heavily on French’s Gazetteer and similar publications.

Letters addressed or presumed to be addressed to Benjamin Mooers appear in the Kent-Delord Collection, Benjamin F. Feinberg Library, Special Collections, SUNY–Plattsburgh, 66.7e; see items 7.1.8, 7.1.9 (1/2), and 7.1.14. Missionary records were accessed in the Drouin Collection on Ancestry.com. Additional information on cross-border families may be found in Virginia E. DeMarce’s Canadian Participants in the American Revolution: An Index (1980).

Wow. Just wow.

Is this time period and locale a particular interest of yours?

Bonjour Ann! Yes on both counts. I am trying to recover lesser-known French-Canadian and Franco-American stories (like those of New York State, which has received little attention) and I am especially interested in the earliest phase of the migration. We still don’t know much about the people who lived outside of giant manufacturing centers. Thank you for reading!