This summer, Query the Past will be offering occasional glimpses of Franco-focused archival collections from northern New England. The University of Vermont’s Special Collections Library is the first stop in this digital journey.

* * *

Readers of “Tout nous serait possible” and this blog may recall Joseph Denonville Bachand (1881-1970), the dentist whose long political journey led him to the Vermont legislature and then to his state’s Commission on Foreign and Domestic Commerce. At the peak of his career, he was the highest-ranking Franco-American in Vermont state government.

Like many Franco-American politicians of his generation, Bachand effortlessly balanced involvement in a variety of ethnic endeavors—the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste, for instance—and participation in the larger arena of U.S. politics. At times, he combined those pursuits, as when he argued that it was in Franco-Americans’ best interest, as a group, to vote for the Republican Party.

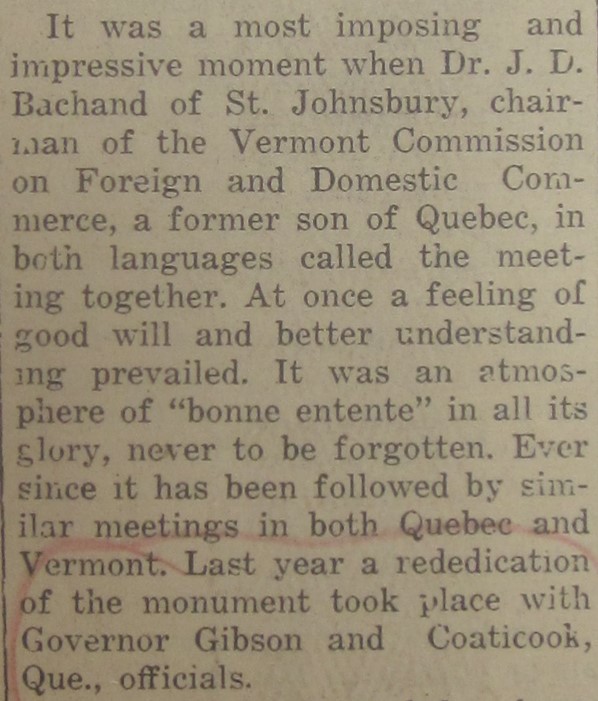

Bachand, a native of Coaticook, Quebec, brought a transnational perspective to the Commerce Commission, which he chaired. He was instrumental in organizing “good will” summits between Vermont and Quebec in the 1930s and 1940s. Evidently, historic ties arising from immigration could serve closer relations and greater economic exchange. In the summer of 1938, that cross-border relationship was cemented almost literally with the dedication of the monument de la Bonne Entente in Stanhope, Quebec, just eight miles from Coaticook. Governor George Aiken and Quebec officials attended.

Bachand was not a “s’cusez, là” Franco-American. In other words, he was not self-effacing or self-deprecating; he did not willingly settle for less. As previously noted, he was, in his own words, “the pioneer of French cultural survival in Vermont.” Nor would he have been able to climb the echelons of the state government and sidle up to the Anglo-Saxon Protestants of the GOP establishment with perfect modesty. He was willing to remind people of his hard work—and of favors he might be owed.

This became quite clear at the end of the 1940s, when Vermont’s historic commitment to small government put the Commission on Foreign and Domestic Commerce on the budgetary chopping block. The legislature’s Appropriations Committee deemed the Commission’s shoestring budget too onerous. Correspondence preserved in Governor Ernest W. Gibson’s papers at the University of Vermont captures Bachand’s reaction.

The battle came in 1949 and led Bachand to buck the natural outcomes of his own party’s approach to government. Vermont Republicans were dedicated to John O’Sullivan’s proposition that “[t]he best government is that which governs least.” The Appropriations Committee received a tentative budget of no more than $500 for Bachand’s Commission. When Bachand protested, Governor Gibson explained that if asked for more, the legislature “might want to do away with this commission” entirely.

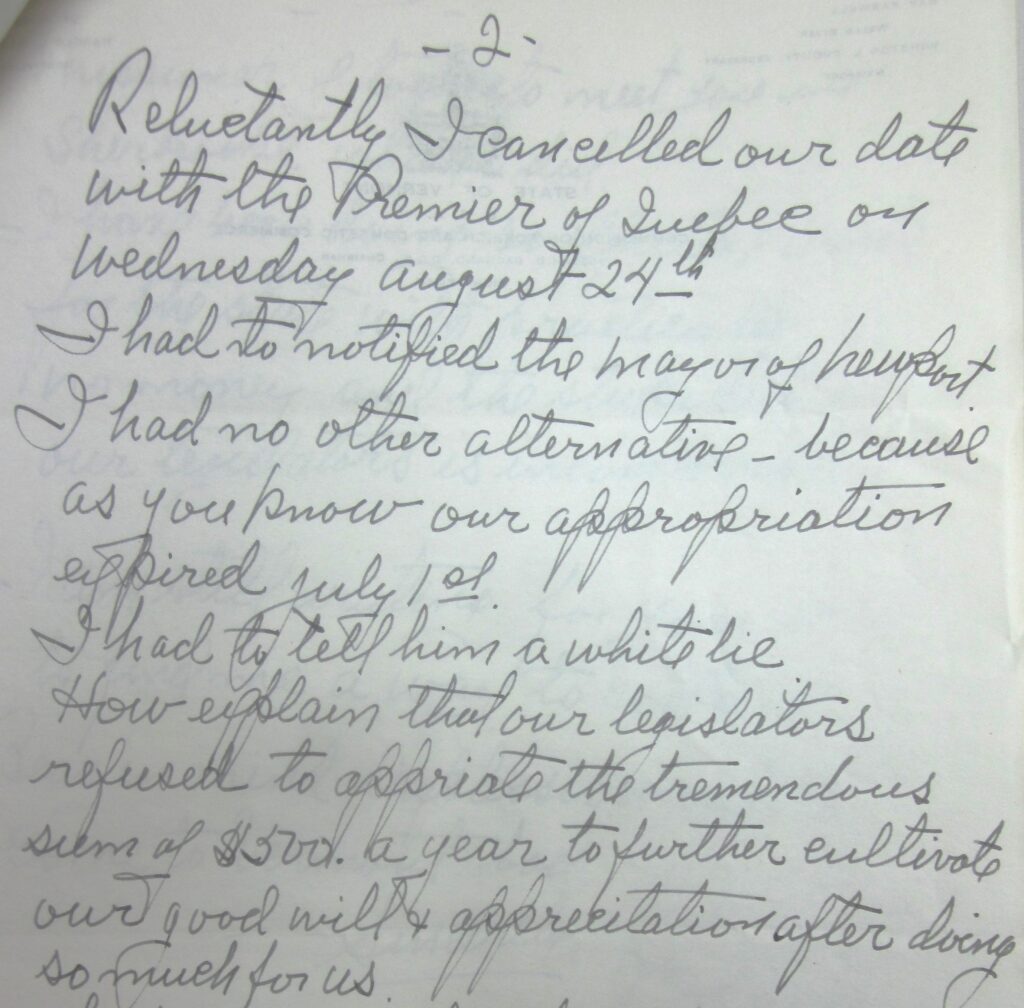

Gibson acknowledged the civil servant’s good work; Bachand, in turn, touted his achievements and prodded the governor into action. “Bear in mind like a good governor,” he wrote in April 1949, “that you are coming to Montreal.” That was vain, for, apparently, the Commerce Commission’s appropriation expired several months later; $500 had been too much. He did not keep his views to himself. He was quick to complain to Gibson that in the absence of a budget he had had to cancel a meeting with Premier Duplessis of Quebec. In one letter, he stated frankly that “the stupidity of our legislators is inconceivable.”

The next one, reproduced here in full, communicated the same frustration:

My dear Governor:

I received your letter of the 17th inst.

It hits the nail right on the head.

It is admitted that I was doing good work by all concerns [sic] who are in the know.

Your last paragraph is the excuse of your chairman of [the] [A]ppropriation[s].

I was spending a little over $300. a year. What would the Premier think of such an explanation, the Canadian newspapers? Is it justified? A drop of water in the bucket. Do we want to laugh at our friends?

Would the people of Vermont approve after due explanation?

I took my pastor to Rock Island and had dinner last night with [John Thomas] Hackett[,] M.P. [Member of Parliament]. We are unanimous in our opinion that it is (the [F]rench expression) c’est grossier et une insulte. The administration of Quebec + the people do not deserve such treatment from the legislature of Vermont nor its ambassador of good will.

It drips with jealousy + prejudices.

It is our opinion.

How a member of the [A]ppropriation[s] told me that never a good word was said in my favor – but objections – objections. It was evident that they wanted to get rid of me regardless of consequences.

Objections came even from one head of a department. I know who it is. He has always been jealous on account of my doing a good job with nothing.

I was in the legislature and I know all about it.

It is really an insult to our intelligence + good will.

Sincerely,

J. D. Bachand

Bachand was still on the job in the fall. His salary may have been separate from the Commission’s budget. He nevertheless maintained pressure on Gibson who, in December 1949, finally stated, plainly, that there was nothing he could do.

A silver lining may have been his continuous reappointment to his role. He was not without allies, either. His hometown newspaper endorsed his work in 1952. “Despite the lack of publicity of his commission,” an editorial read, “Dr. Bachand has been an energetic and tireless worker to improve relations between Quebec and Vermont and to give Canadians in general a better understanding of Vermont. He has devoted much time from a flourishing dental practice to attend civic events in Quebec and other Canadian provinces. He is frequently host to visiting Canadian officials” (Caledonian-Record, July 29, 1952). The editors added that his work was visible in the number of Canadian cars on Vermont roads every summer.

Bachand’s strong words in 1949 are especially understandable in that this was a labor of love for him—so much so that he stayed in the position for another decade. He left government in 1959, just as another prominent Franco-American was poised to make his mark on the state. The next year, Russell Niquette vied for the governorship on the Democratic ticket. Franco-Americans had not become a captive Republican voting block.

Bachand and Niquette together exemplified the promise of Franco-Americanness: they integrated and became indistinguishable from other Americans from a political standpoint—while living out their culture, which is something that several Quebec commentators have missed in their reading of my book. But, of the two men, Bachand’s contribution may have been the most lasting. He helped strengthen trade, tourism, and mutual understanding between natural partners. He would also have appreciated the current volume of exchange between Quebec and Vermont and the creation of common forums, like the French Connections event held in Burlington in 2017.

For more on Franco-Americans in Vermont politics, see my last blog post; on Bachand as a model of francophone bridge-building, see this piece from The Conversation.

Leave a Reply