They went to Corbeau and Whitehall. They went to Vergennes and Highgate. They returned, and again to the Great Republic they went.

This was a proto-industrial era, a time before ubiquitous factories, before national parishes, before the idea of Franco-America could form as something succinct and coherent. These were the early days of French Canadians’ migrations to and from the United States.

We know very little about cross-border migrations between the American Revolutionary War and the 1840s—numbers, reasons, means, destinations, and so forth. The evidence we do have is often anecdotal. We know of this person, at this place and at this time. But was he or she alone, or a symptom of larger phenomena? This question is not hotly debated, but it should be, and there is potentially a groundbreaking study to come of it, if a scholar will only give it the time it merits.

Gradually, the anecdotal has been piling up and pointing towards the significant. Certainly these early migrations undertaken by enterprising—or desperate—individuals matter a great deal if you are sitting in Highgate. Their significance is also patent as we begin to see these individuals as French-Canadian explorers. They were exploring inhabited lands, of course, but also laying out paths for future migrations and reporting on possible opportunities for their compatriots.

Much of their story lies hidden (or rather unscrutinized) in Roman Catholic parish records in Quebec. The following images, taken from the massive Drouin database, hint at what awaits researchers.

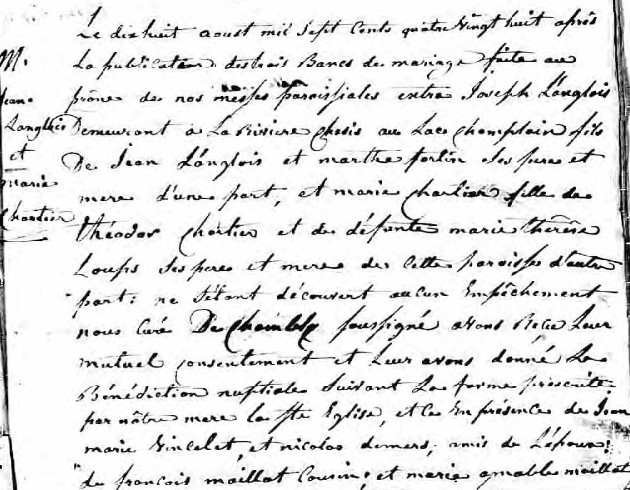

The first meaningful cross-border ties were forged as a result of the Revolutionary War. When peace returned, French-Canadian soldiers who had served in the Continental Army were granted lands in northern New York. The area was remote, but ties to Quebec (or Lower Canada) were not thereby cut. The veterans and their families regularly traveled north to the Catholic parishes on the Richelieu River to baptize children or to marry. This exchange began as early as the 1780s and may have been encouraged as trade on Lake Champlain and the Richelieu grew after 1795.

Many such early records come from Chambly, for a time the southernmost Catholic parish on the Richelieu. There we find the names of veterans and their families—Amelin, Bélanger, Gosselin, and so forth.

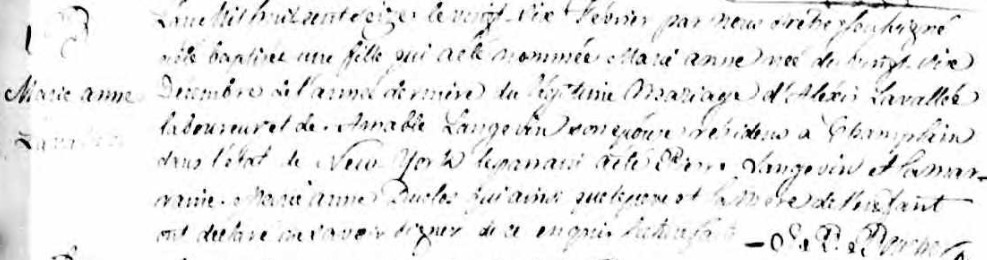

La Prairie, across from Montreal on the south shore of the St. Lawrence, also had its ties to the Lake Champlain settlements. The Lavallée family appears recurrently in local records as having members settled near the border. One such record dates from 1811. We may suspect that the Lavallées were related or forged ties to a Revolutionary War soldier.

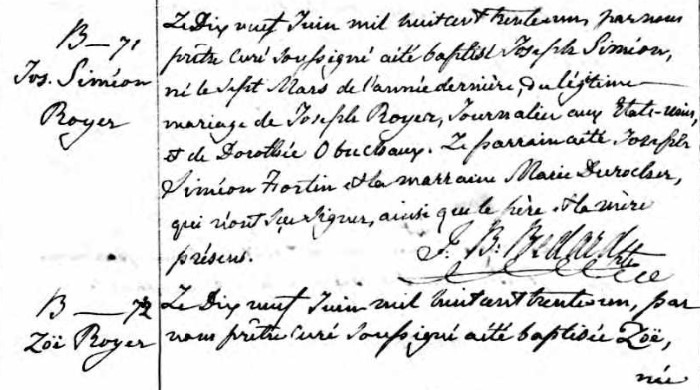

Some of my ancestors occasionally wandered onto U.S. soil—early in the twentieth century, sure, but also around 1830. Joseph Royer worked as a journalier, a day laborer, in the U.S. and eventually settled in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, a region that was then almost as American as Vermont. Joseph and Dorothée Royer’s daughter, Zoé, was married by a Catholic missionary to Edouard Lacroix at the dubious age of 15.

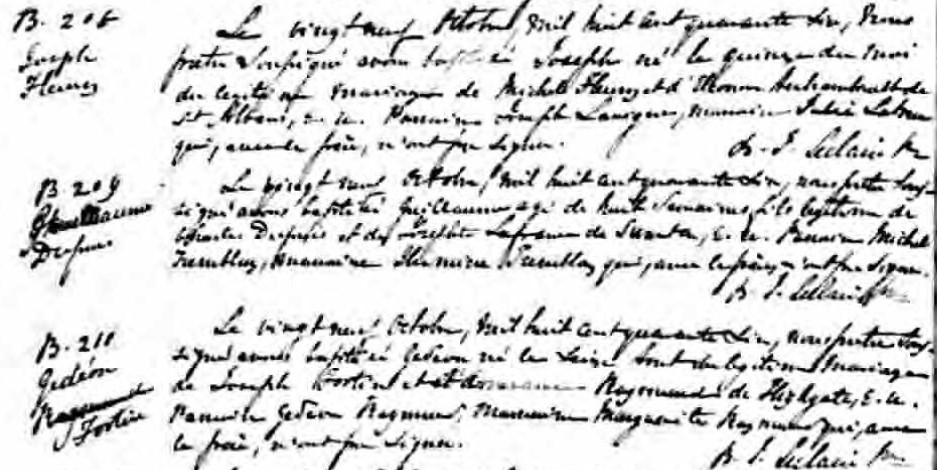

The line between Catholic parish and mission was often ambiguous both in the Eastern Townships and in northern Vermont and New York. In Stanbridge, Quebec, near Lake Champlain, baptism and marriage records from the fall of 1846 list a large number of people residing in the U.S. Did these French Canadians travel together to Stanbridge to benefit from Catholic rites? Or did the local priest cross the border to bring the Church to them? More research is needed.

On the image below we find individuals from St. Albans, Swanton, and Highgate, Vermont.

We now know that Canadians (okay, British North Americans of French-Canadian descent) fought in the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), so it should come as no surprise that even in the pre-railway era, people from the St. Lawrence River valley made their way throughout the U.S. Northeast. They took on a wide variety of occupations in numerous unsuspected locations.

The Richelieu and Lake Champlain axis was the earliest migratory avenue, but by no means the only one, as Canadians increasingly made their way to the Madawaska region and, from the Beauce, to central Maine in the nineteenth century. Parish records suggest that the field of research is broad in its documentary base; it is all the more so geographically.

Readers should consider this an invitation.

I take this opportunity to recognize the efforts of the Franco-American Centre at the University of Maine, which, going above and beyond its stated mission, continues to hold virtual events and to connect people with an interest in all things Franco.

Additionally, those who may be enjoying these blog posts may also want to check out My French-Canadian Family, a new website that aims to connect French culture in Quebec and the United States. New content is posted to the blog regularly.

At last, last year I had an enriching discussion with Jesse Martineau of the French-Canadian Legacy Podcast on the Rebellions of 1837-1838 and their historical background. Our conversation is now available online. The podcast shares new content every week, including full-length interviews every other week. Its essential contribution to Franco life is very much worth supporting.

Leave a Reply