The latest issue of Le Forum, published by the Franco-American Centre in Orono, carries my article on Hattie LeBlanc, an Acadian migrant accused of murder in Waltham, Massachusetts, in the early twentieth century. We know of Hattie from the extensive press coverage of her trial. Yet, in many respects, she is an exception, for the migrations of Acadians (that is excluding the forcible displacement of the 1750s) remain little studied by researchers and little known of a wider public. The French-Canadian grande saignée has, for one thing, overshadowed its Acadian counterpart simply by virtue of numbers. In many areas, the Acadians were gradually absorbed into a larger Franco-American community. There is another aspect to the story. Many Acadians—Hattie LeBlanc among them—returned to their native communities in Canada, after which they married and raised children, such that subsequent generations were little touched by American sojourns.

Young Hattie left West Arichat, south of Cape Breton, in 1908. Whereas some of her stepsiblings had previously gone to work in Gloucester, Massachusetts, Hattie’s journey by rail took her to Waltham. The LeBlancs’ travels occurred at the height of mass migration to the United States, which occurred roughly between 1880 and 1930. The first decade of the twentieth century may be seen as the critical period of Acadian migrations due to the attention the issue then elicited among Acadian community leaders. The proceedings of Acadian “national” conventions in Canada suggest as much.

Delegates to the convention held in Arichat, of all places, in 1900 created a commission focused specifically on Acadian exiles; Rémi Benoît of Lowell was its reporting secretary. Speakers at the conventions of Caraquet (1905) and Saint-Basile (1908), in New Brunswick, warned strongly against emigrating. Beyond the dangers of life and work in American cities, emigration undermined domestic colonization projects and, as Fr. Philippe Belliveau stated, reduced Acadians’ numerical weight within their respective provinces. Agriculture would be the salvation of the people, although Belliveau did support industrial development (as had occurred in Sydney, Amherst, and Moncton) as a means of keeping Acadians on Canadian soil.

The speakers at these conventions regretted emigration, but generally did not disparage those who went abroad. In 1905, Judge Pierre-Amand Landry explained that he had initially seen expatriation as a calamity. Although still wishing to keep his compatriots on their native soil, he conceded that emigrants were organizing themselves and preserving their language abroad. Senator Pascal Poirier celebrated the emigrants’ “enlightened and zealous [Acadian] patriotism.”

Landry’s and Poirier’s cautious optimism about the cultural fate of emigrants owed primarily to the Société mutuelle l’Assomption, a mutual benefit society established in Waltham in 1903. Like the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste and the Association Canado-Américaine, the Société l’Assomption provided a basic safety net to members and their families in addition to its cultural activities. Rémi Benoît served as its first president. In less than a decade, the organization had nearly one hundred chapters. American-based delegates to the second convention, held in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, came from Cambridge, Charlton, Chelsea, Gardner, Lowell, Lynn, New Bedford, North Oxford, and Waltham. Rumford, Maine, appears to have been the only U.S. location outside of Massachusetts to be represented. American leadership would be undercut in 1913 when the headquarters were relocated to New Brunswick.

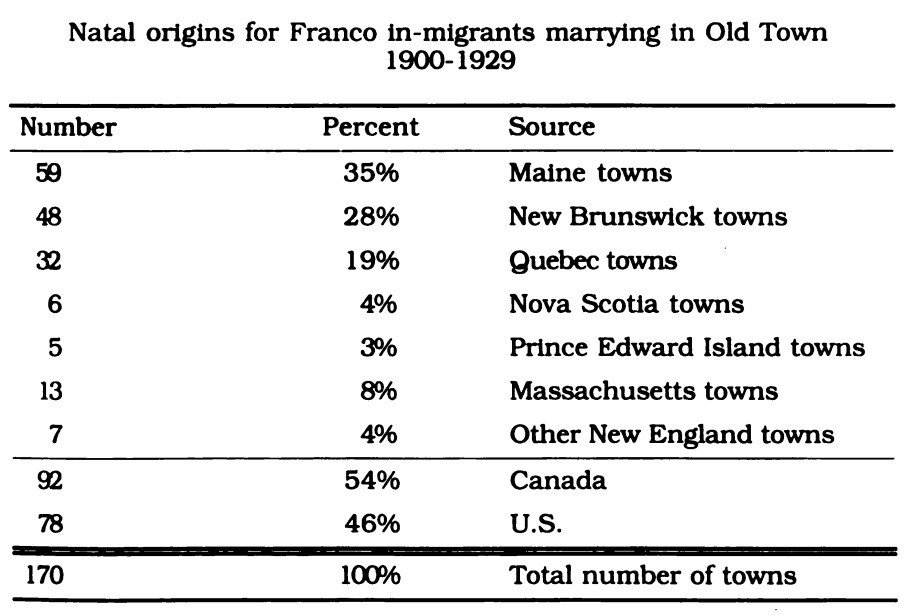

As with the Quebec migration, close relationships developed between specific places of origin and American destinations. Through the back-and-forth of seasonal and temporary migrations, those places developed symbiotic relationships. Whereas Nova Scotian communities sent thousands to Massachusetts (perhaps a legacy of employment opportunities in boatbuilding and the fisheries), areas of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island contributed significantly to the Acadian presence in Maine. While the LeBlancs were journeying to the Bay State, their compatriots from other provinces were taking advantage of employment in the newly flourishing paper mills. In “Franco-Americans in Maine: A Geographical Perspective,” published in Acadiensis (1974), James P. Allen explained:

Acadians from New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and the upper St. John Valley migrated in handfuls to most of the urban French centers in Maine, but the paper mill towns received easily the largest numbers. For example, in 1880 the S. D. Warren Company in Westbrook was described as the largest paper mill in the world; its employees included Québécois, but these were later joined by about one hundred Acadian families. Some P.E.I. Acadians settled near the new mill in Yarmouth, and others made their way to the Chisholm and Riley mills in the town of Jay. Millinocket’s Franco-Americans came mostly from the upper St. John Valley and the Maritimes, and the largest colony of New Brunswick and P.E.I. Acadians developed in Rumford after the International Paper Company opened its sulfite mill and paper bag plant in 1900.

Evidently, we have some basic understanding of the main fields of migration. Qualitative sources on Acadian migrations between the Maritime provinces and New England, particularly the records of Acadian conventions and organizations like the Société l’Assomption, have served us well in this regard. But research has been held back by the methodological challenges involved in quantifying the Acadian presence. The essential question—how many?—continues to hover over the field.

Forty year ago, Fernand Arsenault wrote that “[e]xact statistics covering Acadian emigration to the United States are not available.” Lo and behold, four decades have passed and Arsenault’s words still ring true—but not without reason. Any reliable estimate must involve triangulation from a variety of sources.

Some of that evidence lies in Canadian census records. We might think of Augustin and Elisabeth LeBlanc, who lived in East Pubnico, Nova Scotia, in 1911; their three children were all born in the United States. Sisters Louise and Adelle Amirault, both residents of Tusket, were born south of the border at the turn of the 1870s. Yet, Canadian records vastly underestimate the number of repatriates, for an American sojourn was, for many Acadians, a brief phase of their young life. This was to some extent a migration of young, single people, many of whom saved up and returned to establish households in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. As for net migration, as some scholars have done for Quebec, it is still possible to estimate the average natural growth rate and compute departures from “missing” people at the end of a given decennial period. Neil Boucher (Steeples and Smokestacks, 1996) did exactly that on a local scale and found a net loss of approximately 3,600 people in Digby County, Nova Scotia, between 1871 and 1911. That figure amounts to one emigrant for every 12 residents of the region in 1911.

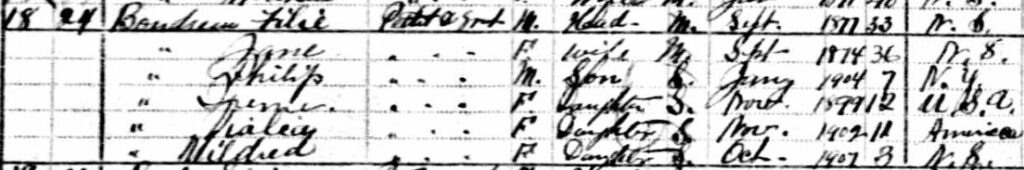

U.S. census returns are, unfortunately, of little use if a systematic count is the object. The census of 1910 for Old Town and Rumford, Maine, makes this clear: the enumerators did not give the province of origin, merely separating Canadians into “French” and “English” instead. One would have to study surnames to distinguish French Canadians from Acadians, an approach with its own limitations. Researchers must thus turn to U.S. vital records, alien registrations, records of border crossings, and a patchwork of local documentation—no small project. In the 1970s, Fr. Clarence d’Entremont fell back on rough estimates from the interwar period. In 1923, a Moncton newspaper stated that Acadians in the United States then numbered 50,000; in the mid-1930s, a writer offered a figure of 40,000.

Ultimately, we must recognize that Hattie LeBlanc, an expat at the age of 14, was part of something larger but, from our contemporary vantage point, hazy. We have rescued one dramatic story; the Acadian context will also require sustained attention. By the tens of thousands, Acadians left their home provinces for some of the same reasons that sent French Canadians abroad, although commercial competition in the fisheries was an important factor. Their experiences, occupations, and destinations were as diverse as those of their counterparts from Quebec. From Millinocket to New Bedford, Acadians worked as mill operatives, domestic servants, seamstresses, carpenters, fishermen, and unspecified laborers.

We have to wonder whether Hattie saw herself as taking part in that larger Acadian story—something beyond the immediate needs and experiences of her kinship network. Considering the variety of places of origin and the challenges involved in constructing a Maritimes-wide Acadian identity, that seems doubtful (much more so because anglophone Nova Scotians were also heading south in high numbers). But that should not keep us from the aggregating work that will reveal the U.S. Northeast’s other French story.

For anyone seeking more information on late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Acadian migrations, Phyllis LeBlanc will be discussing the topic as part of the Acadian Archives’ lecture series this winter. Follow the Acadian Archives on social media for regular updates. The story of Hattie LeBlanc is available through the Franco-American Centre’s DigitalCommons space.

Please feel free to share your own Acadian-American story in the comment section below.

A Note on Sources

The proceedings of turn-of-the-century Acadian conventions are available in Denis Bourque and Chantal Richard’s Les Conventions nationales acadiennes 1900-1908 (2018). See, on the second convention of the Société l’Assomption, “Societe l’Assomption,” Fitchburg Sentinel (July 24, 1905), 5. A meeting of Massachusetts Acadians in Boston seems to have drawn a substantial female presence; see “Acadians in Reunion,” Boston Daily Globe (April 19, 1907), 4. There is more on the Société l’Assomption on the Francophonies canadiennes portal of the Université Saint-Boniface.

Guidance on the topic is available in secondary works, starting with strong dissertations that discuss Maine Acadians by James Allen (Syracuse University, 1970) and Marcella Harnish Sorg (Ohio State University, 1983). An essential source is L’émigrant acadien vers les Etats-Unis, 1842-1950 (1984), a collection of essays resulting from one of the French Institute’s annual colloquia. Five of the essays appear as chapters in Steeples and Smokestacks. Works by Canadian researchers on outmigration from the Maritimes generally lump Acadians with other groups but can nevertheless help identify larger patterns.

Marguerite Maillet’s text in L’émigrant acadien vers les Etats-Unis reminds us of the substantial attention given to emigration in the early twentieth century, particularly in literature. Fr. Arthur Mélanson penned Retour à la terre and then Pour la terre. A story titled Placide, l’homme mystérieux appeared serially in 1904. James Branch published a play, L’émigrant acadien: Drame social acadien en 3 actes, in the 1920s. All of these works celebrated traditional values and used emigrant stories as cautionary tales. Antonine Maillet’s Pointe-aux-Coques later touched on estrangement from the native parish.

Other essential texts include:

- Clarence d’Entremont, “The Acadians in New England,” New England, Acadia, and Quebec, ed. by Edward Schriver (1972).

- Betsy Beattie, “‘Going Up To Lynn’: Single, Maritime-Born Women in Lynn, Massachusetts, 1879-1930,” Acadiensis (1992).

- Yves Otis and Bruno Ramirez, “Nouvelles perspectives sur le mouvement d’émigration des Maritimes vers les Etats-Unis, 1906-1930,” Acadiensis (1998).

- Julie Williston, “L’émigration des femmes célibataires acadiennes vers la Nouvelle-Angleterre (1906-1924)” (M.A. thesis, Université de Moncton, 2016).

More recently, Carmen d’Entremont has studied migratory and cultural ties between the Argyle region of Nova Scotia and New England.

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - December 2, 2023 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte