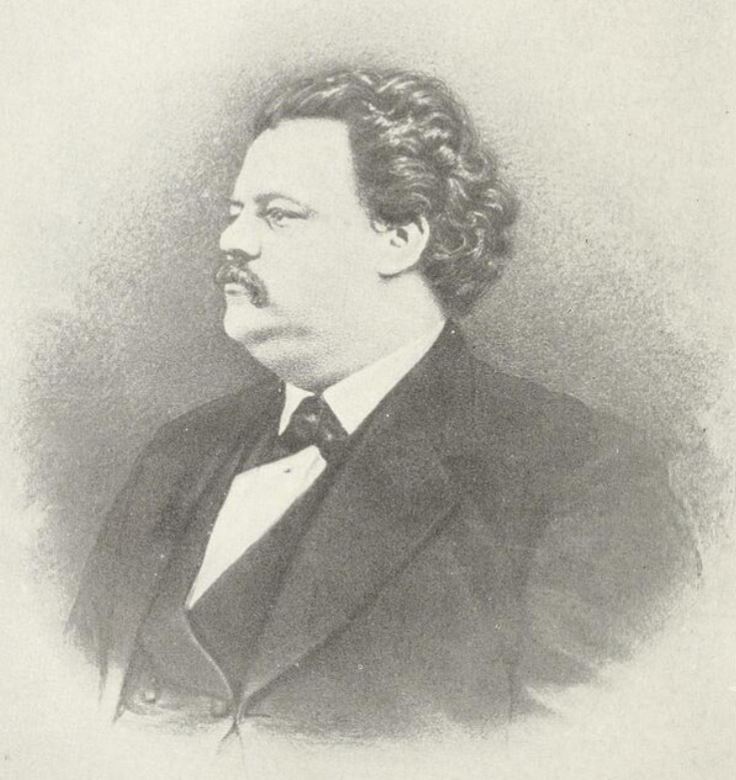

In some Franco-American circles, nearly 140 years after his death, Ferdinand Gagnon still benefits from instant name recognition. Gagnon was an ardent defender of French-Canadian culture in the United States and he became known as the father of the Franco-American press. He founded and edited Le Travailleur in Worcester, Massachusetts; this was one of the first successful Franco-American publishing endeavors. Unlike most of its contemporaries, Le Travailleur, though also battling financial insecurity, survived its first few years. Its articles were widely reprinted and helped establish Gagnon as one of the most influential Franco-American leaders of the 1870s and 1880s. In Manchester, a statue honoring the editor was installed in Lafayette Park on the centennial of his birth; today, a Facebook group committed to dialogue between Franco-Americans and their cousins in Quebec bears his name.

As time passes, historical figures are gradually eroded to their most essential accomplishments (or their most notorious deeds). We cannot expect to retain all things of all who preceded us. Inevitably, of course, as these figures become one-dimensional, we lose a great deal of that which made them unique or significant. So it is with Gagnon. In his case as in others, there was a conscious effort, in the wake of his death, to move past controversies and fashion him into the Franco-American par excellence—a rallying point representing all that French-Canadian immigrants held in common.[1]

As Gagnon was born on this day in 1849, we have the perfect opportunity (or pretext) to add layers to the story we inherit.

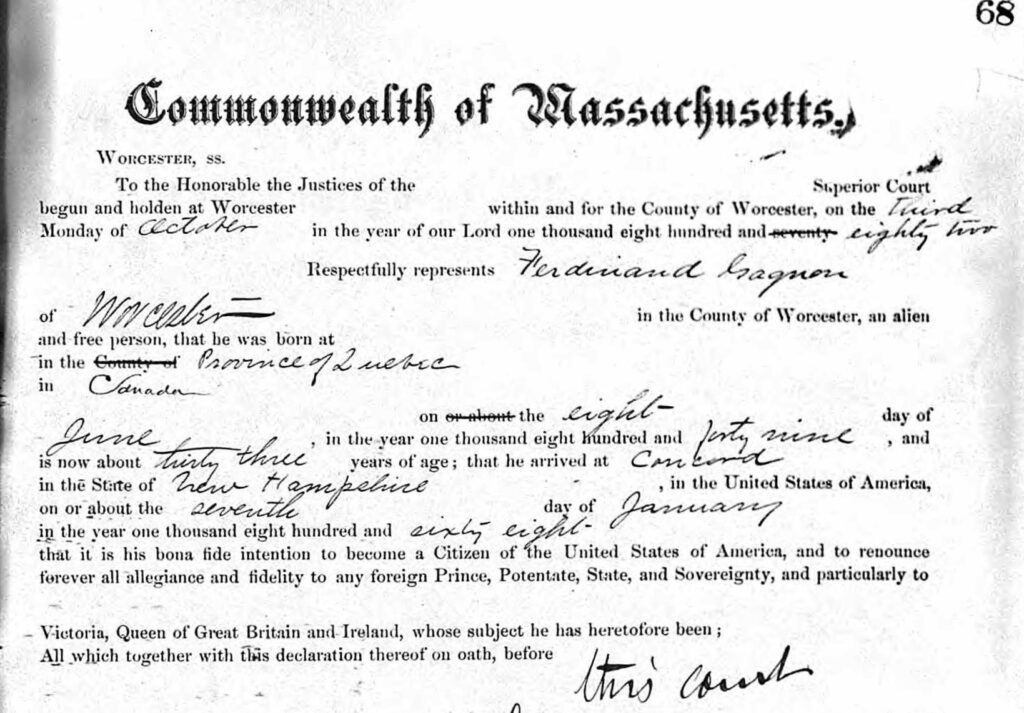

A native of Saint-Hyacinthe, Ferdinand Gagnon immigrated to New Hampshire at the age of 18. He quickly became an unapologetic spokesperson for his fellow Canadians. He stood up for the legitimacy of French-Canadian culture as something distinct but complementary of American institutions. His shining moment, in this respect, came in 1881, when a Massachusetts civil servant identified the immigrants as birds of passage who were working on U.S. soil momentarily—though long enough to drive down wages—without contributing to the host society. The author of those remarks also used racializing language in reference to French Canadians, which, to the latter, seems to have been the most objectionable charge. Gagnon forcefully challenged the allegations in hearings organized by the Massachusetts Bureau of Labor Statistics:

Canadians do not go back to their country in a large number, as is believed by many manufacturers. Leaving their relatives in Canada, being at a short distance they go often to visit their friends, but come back to the States to their usual occupations . . . During the last ten years the Eastern States have received the greatest bulk of the Canadian immigration, and already we count over thirty churches built by them, many schools, and a great many are real estate owners … The report says that Canadians do not care to vote, — another error. The informants had forgotten, probably, that the law requires a residence of five years in this country for an alien to become a citizen . . . [I]t is yet surprising to see so many Canadians who are citizens of the United States.

Like his fellow witnesses, Gagnon overstated the case. But most striking in all of this were his prior efforts, which might have given ammunition to French Canadians’ contemners. In the 1870s, aiming to repatriate migrants in the United States, the federal government in Canada and its counterpart in Quebec hired agents to recruit families for colonization schemes north of the border. Gagnon was one such agent. He distributed information about the “colony” of La Patrie in Quebec and provided reduced train fare to return migrants. He sought to deter ordinary French Canadians from settling in the United States. At that time, if Gagnon was a community builder, it was in aid of developing farming communities in the Eastern Townships. Amid the prosperity of the early 1880s, a resurgence of immigration, and the failure of colonization policies, he would refocus his efforts on the welfare of an expanding Franco-American world.

This commitment to the Northeast’s French-heritage population did not merely involve the struggle against slander like that purveyed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. In the 1880s and 1890s, this population found itself embroiled in religious controversies in several areas of New England. The question was often whether national (ethnic) parishes served by French-Canadian priests were a right granted by the Catholic Church or a mere privilege. In Fall River, the appointment of a priest of Irish descent to the parish of Notre-Dame moved the debate out of the realm of theory. Ordinary immigrants and their community leaders protested with a ferocity that led the bishop of Providence to place the church under interdict.

One might have expected Gagnon to stand on the barricades. Well, that was not the case. In Le Travailleur, in the fall of 1885, he would state,

Let us be prudent in our actions, let us be serious in our deliberations, let us seek counsel from our superiors and our friends before we act, and let us follow their advice; no impulsive movements, no misplaced enthusiasm. Let us wait for the favorable time and formulate our demands with the greatest respect, and we will be favorably heard by those whose mission it is to teach us.

Gagnon was a child of the Church and sought to exercise deference and avoid scandal. He was also realistic about the balance of forces in the struggle with seemingly unsympathetic bishops.[2] The protests and confrontations of the prior year had done little for the parishioners of Notre-Dame and the Catholic faithful in general. Caution, diplomacy, and patience were, in this case, operative words, in his view.

This situation stands out because in many other confrontations caution, diplomacy, and patience seemed entirely foreign to the editor’s character. Gagnon was passionate. He did not mince words. Like many contemporaries, he was uncompromising when defending his honor, his position in the community, and his values. His feud with Honoré Beaugrand has been documented. Well, there were many feuds.

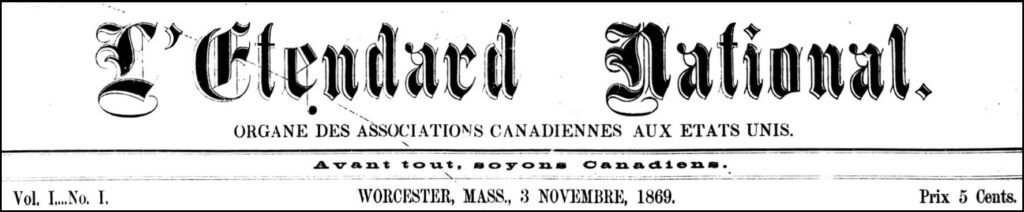

We might turn the clock back to 1869, when Gagnon was producing L’Etendard national, a predecessor of Le Travailleur. A war of words erupted between Gagnon and Médéric Lanctôt. Both had been educated in Saint-Hyacinthe; both had strong views. In the late 1860s, they were both trying to carve out space for themselves as persons of consequence. They were also wrestling for the soul of the nascent thing we know as Franco-America. Ultimately, both would die before the age of 40.

The feud may have arisen precisely because of the similarities and the ground they shared. Lanctôt had attempted to launch a paper in Worcester in 1869 and failed. Months later, Gagnon founded L’Etendard. There were, of course, ideas at the heart of the controversy. After his failure in Massachusetts, Lanctôt traveled west and attended the French-Canadian national convention in Detroit. There he injected politics—and divided a common cultural front—by broaching the issue of the American annexation of Canada, which he favored. Gagnon opposed annexation and, especially, the way in which the issue had been drawn into convention proceedings. Lanctôt responded by questioning the genuineness of his counterpart’s principles.

In a four-column editorial in only the fifth issue of L’Etendard, Gagnon defended himself and went further. He was not a tory, as the radical Lanctôt claimed, but had always been a Liberal in Canadian political and he had always supported Canadian independence. Lanctôt, on the other hand, had continually tried to capitalize on others’ success—all for his own ego. Gagnon called him a troublemaker, a hypocrite, a pitiable small man on the cusp of impiety, a lunatic, and worse. Several weeks later, Le Travailleur acknowledged the “diss track” issued, in turn, from Detroit. The war of words continued and it seems the young Gagnon would have had little time for the cautionary advice he offered his countrymen in his final year.

This was not particularly exceptional. Even if we imagine that French-Canadian immigrants were marching in lockstep in defense of their culture, personalities and politics interfered and made for regular conflict. Gagnon engaged with these battles.

Ferdinand Gagnon can still strike us as a larger-than-life figure. In many ways he was. He left a lasting legacy that established a model for other community leaders to follow. At the same time, he was a complex figure and his views evolved; he was more deferential than we might suspect in some areas and more contentious in others. His life and legacy are made the richer for all of this. By adding all of this color to Gagnon’s life, and doing likewise for his contemporaries, we stand to make the Franco-American historical narrative more vivid and let it speak to the complexities of our day.

[1] This was done at the Rutland Convention of 1886, held months after his death, but also through later published works.

[2] I complicate this story in the Catholic Historical Review.

Leave a Reply