An earlier version of this essay appeared en français in the spring 2018 issue of Le Forum, the quarterly publication of the Franco-American Centre (University of Maine).

* * *

We stopped at Mountain View on a gloomy and intensely cold December day. Thanks to a volunteer who tends to the cemetery, we had at long last located Jerry’s final resting place—the earthen shroud of a man we had in fact never met. Despite the many generations separating us, he became “mononc Jerry.” Some fifteen paces in, we spotted the diminutive stone. Long ignored and eventually forgotten, Jerry had visitors again. In our small way, we communicated with our forebears.

Surviving documents chronicling the life and death of Jerry Cross tell a tragic tale. That’s what drew us in the first place. We felt we owed him that which he had not quite found in life or death. But it wasn’t simply a sense of moral responsibility. With him, we rediscovered an aspect of the French-Canadian diaspora that is too often overlooked. Jerry’s story invited us to explore the boundaries and borderlands—also ignored and overlooked—of Franco-America.

Jerry Cross was first and foremost Jérémie Lacroix, born in West Brome in the Eastern Townships of Quebec in 1855. His generation and that which preceded it were early witnesses of the grande saignée, the first wave of mass emigration of French Canadians. Some families left the St. Lawrence valley to settle in the Eastern Townships; others crossed into the northeastern United States. Members of the Lacroix family found homes in both regions.

My ancestors left Sorel and the Saint-Hyacinthe area to farm in the back settlements of the old seigneuries. Jerry’s grandparents were among the first French Canadians in the southern part of the Townships—ever slowly pushing the cultural boundary and helping to create a new borderland region on Quebec soil. Edouard Lacroix and Zoe Royer, Jerry’s parents, were married by a missionary priest in 1844. They lived in Brome Township for nearly the rest of their lives. In the same period, other young families were feeling the narrowing of opportunities due to rapid demographic growth along the St. Lawrence. When Zoe gave birth to Jerry, at least four of his paternal uncles were living in Vermont.

As a young man, Jerry followed in their footsteps. He left his parents’ hearth to work as a day laborer and hopefully amass the means that would enable him to found his own household. In 1875, he and Sophie Brosseau were wed in St. Albans, Vermont, Sophie’s birthplace. Franklin County, in the northwestern corner of the state, had a substantial Canadian population as early as 1850. That was still true a generation later.

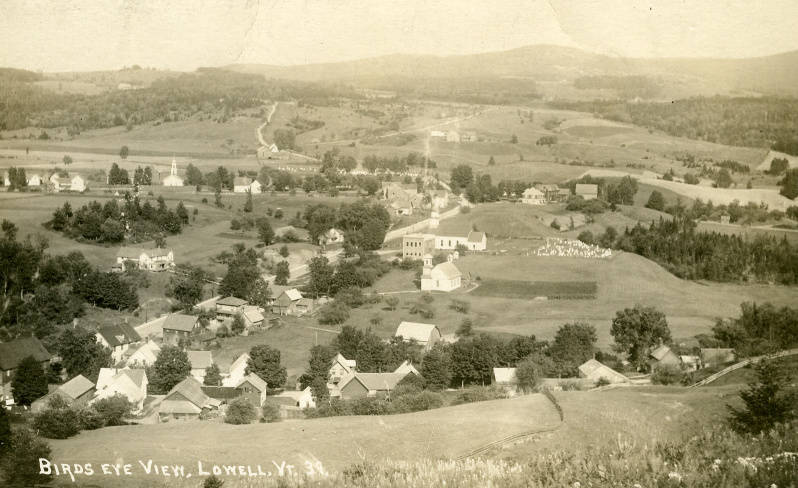

In 1900, Jerry, Sophie, and their children were living in Lowell—but not the well-known Massachusetts spindle city. While a sustained movement of people increasingly connected the Quebec countryside to Boston’s industrial periphery, migration between contiguous rural regions continued. It was in Lowell, Vermont, that the family was then living. Like many other families of French-Canadian descent, they remained true to their ancestors’ agricultural vocation through the migration process. Ten years later, we find them in Coventry, near the southern point of Lake Memphremagog. The eldest daughter was a thirty-something widow who had returned to live with her parents. She would marry a Newport man the following spring.

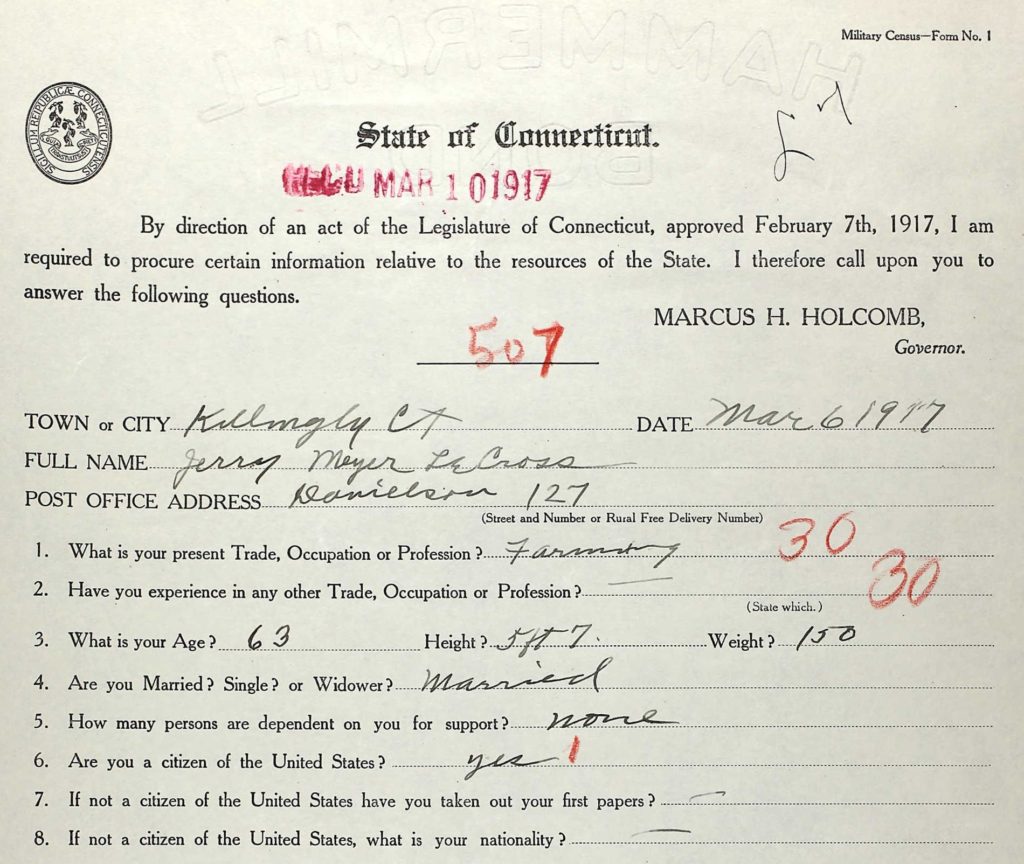

Jerry, Sophie, and the family would move again, a sign that their lives were still unsettled from an economic perspective. In 1917, Jerry—with or without Sophie—was living with their son Fred in Killingly, Connecticut. This area is best known to historians for the Danielson affair, a controversy that pitted survivance activists against the Roman Catholic bishop of Hartford. Local Franco-American elites sought, in the 1890s, to obtain a pastor of their own cultural heritage and regular French-language education in religious schools. That was well beyond the Cross family’s social and cultural universe. Jerry seems to have self-identified as Cross rather than Lacroix; he had grown up in a predominantly English-speaking region of Quebec and, like his wife and children, had bathed in a bicultural and bilingual world. It would appear that their devotion to the Catholic Church was also far from zealous. When daughter Clara married Arthur Barbeau in 1911, it was at the parsonage of Coventry’s Congregationalist church.

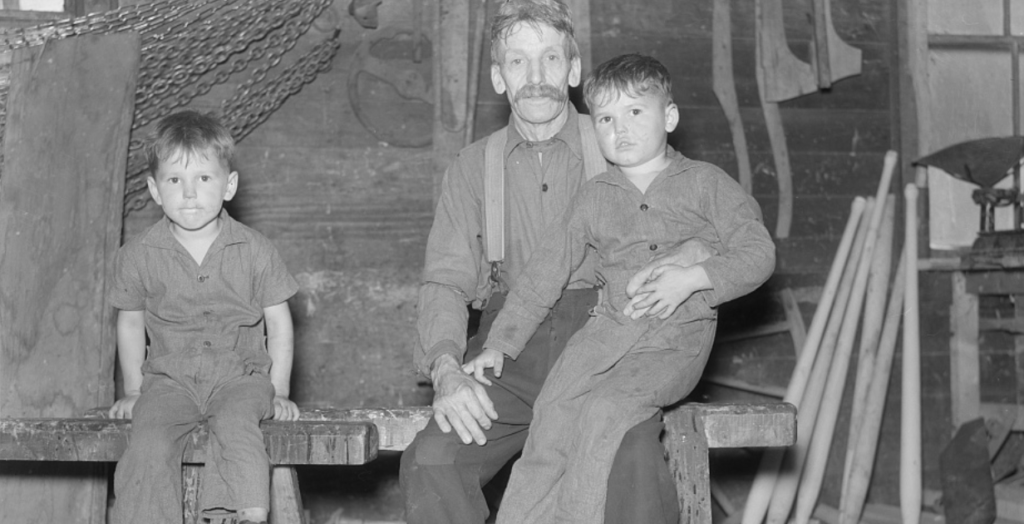

Are these the traitors over whom Quebec wasted so much ink in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? Well, before they could think about survivance, the Crosses had to survive in a more literal sense. The range of options for a family that at one time lived on a town farm, while in Vermont, was extremely limited. In any event, they may have preferred life in the United States. These were not professional ideologues, as their modest circumstances made plain.

On the eve of the United States’ declaration of war, in 1917, the Connecticut legislature authorized a census of state resources and manpower. Thanks to these larger circumstances we finally glean something of a portrait of Jerry. He was listed as a 63-year-old (62, really) farmer. He was a man of modest stature: 5’7” and 150 lbs. He could lead a team of horses, but of steam engines, telegraphy, electrical work, and automobiles he knew nothing. Fred, for his part, belonged to a new world. Although in time he would return to farm in Vermont, he worked in a textile mill following the First World War.

Jerry returned to Lowell, Vermont most likely in the fall of 1917. Around this time a fracture appears to have taken place. His wife of over 40 years, Sophie, left. With what little information survives, the looming “why” may never be answered. We could imagine any number of personal failings—alcoholism, abuse, a poor work ethic. We could also think of less dramatic reasons. If Sophie was ill, perhaps she was better off living with children while Jerry found work where he could. We simply know that Mrs. Cross did move in with her eldest daughter and her stepson. They lived in Newport for a brief time, but by 1921 they were back in the St. Lawrence valley. Sophie died in Saint-Lambert a few years later.

And Jerry? The tragedy of his last year should not obscure whatever failings he may have had; no less, they invite compassion and pity. Alone and weathered beyond his years, he moved into the Bousquet household in Lowell. On June 6, 1918, he settled on his fate. His final act reverberated into the Burlington Free Press: “Jerry Cross, aged about 70 years, committed suicide last Thursday morning by hanging himself . . . At breakfast he appeared as usual, going from the house, directly after the meal, to the barn, where he committed the deed.” He thus followed Truman Lockwood, also a Lowell resident who, six months earlier, had put an end to it all in very similar circumstances. Barton’s Monitor added that “being in poor health [Jerry Cross] became despondent and committed suicide Thursday . . . His family has been separated for some time and none of the near relatives were able to attend [the funeral].” His wife’s departure and the sense that he was becoming a burden may have been the last blows. The Congregationalist minister presided over the final ceremonies.

What remains of Jerry, more than a century later? His final months invite reflection that is more emotional than historical: we should all count our blessings and care for one another. But historical takeaways there certainly are. Jerry’s circumstances—as with those of his French-Canadian neighbors in St. Albans, Lowell, Irasburg, and Coventry—remind us that not all Franco-Americans lived and breathe textile mills. When we stopped at Mountain View Cemetery, just up from the Missisquoi River, in rural Vermont, we acknowledged a story that requires further exploration.

This “mononc” points to the multiplicity of Canadian experiences on American soil from the 1770s to the present day, experiences that defy monolithic identities either prescribed by Franco elites or ordained by Anglo-Saxon assimilators. If we do not recognize migrants’ individual agency out of compassion, then we must do so in the interest of a more complete historical narrative.

* * *

For those reading this on September 3, Professor Susan Pinette (University of Maine) is scheduled to speak virtually on “Writing Franco America in English,” courtesy of the Lewiston Public Library, this evening. More information is available on the library website.

Additionally, in regard to non-traditional Franco-American stories, my work on Canadians in the Mexican-American War is now accessible on the publisher’s website. It will soon be more widely accessible through Project Muse. A sneak peek is available on this blog.

Leave a Reply