The deportation of thousands of Acadians that began in 1755 left human fragments across the Atlantic world. Few areas are known specifically for their Acadian culture—or named after the culture. New Brunswick’s Acadian peninsula stands out… figuratively and literally. It is the horn that juts easterly from northeastern New Brunswick. It is bound by the Baie des Chaleurs and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The region has a history distinct from other Acadian regions and a culture that is still thriving. It also happens to be an ideal vacation destination.

It wouldn’t take much to believe that New Brunswick is a child of Quebec and Maine though raised by Nova Scotia. The blend of geographical features, cultures, and institutions would at least suggest as much. The province does not have as clear an identity or a brand as its neighbors, unless it is its pluralism. Many Canadians know New Brunswick chiefly as the only officially bilingual province in the country. To paint with a broad brush, about two-thirds of residents claim English as their maternal tongue; slightly less than one-third, French.

The Interior

Acadian New Brunswick stretches in a crescent through the northern and eastern parts of the province, with one tip in Grand Falls and the other in the Moncton area. Edmundston and the area along the St. John River have a unique Brayon identity that bears the influence of Quebec. The greatest influx of settlers in this region came not from old Acadia, but from French Canada. That changes as one travels inland.

From the Trans-Canada Highway, the road to the Baie des Chaleurs—Route 17—leads through only two towns: Saint-Quentin and the smaller community of Kedgwick. With the exception of town centers and a small patch of farmland between them, the area is entirely forested. This is not “the forest primeval,” however: invasive species, settlement, and logging have produced a wilderness entirely different from that known to Indigenous peoples and European visitors centuries ago. Kedgwick remains inextricably connected to forestry with a large sawmill and a lumber museum. Opportunities for outdoor adventures abound with the Appalachian Trail, which shadows Route 17 to Campbellton and then to the Gaspé peninsula, and with nearby Mount Carleton Provincial Park, home of the highest summit in New Brunswick. The landscape is reflected in the churches of Saint-Quentin and Kedgwick, both influenced by the peaks and valleys of Dom Paul Bellot’s architectural style.

Saint-Quentin is a francophone town; this traveler found a French that could just as well be spoken in Quebec. Founded as a colonization parish in the early twentieth century, it has lately welcomed immigrants and refugees from the Philippines, Mexico, and Ukraine. More than twelve nationalities are now represented at the local high school. If Acadian colors are little seen in Saint-Quentin, they are very visible in public spaces and on private properties in Kedgwick. That may be a legacy of the late 1970s, when then-pastor Armand Plourde ran for a legislative seat under the banner of the Parti acadien. (That story was memorialized in a documentary now available from the National Film Board.)

Along the Restigouche

The descent towards Campbellton offers beautiful vistas and a taste of the wilderness areas that brought sporting camps, usually for the wealthy, to the Matapédia, Restigouche, and Upsalquitch rivers. With its 7,000 or so residents, Campbellton is the smallest of New Brunswick cities. It can be quite bustling. Here begins the land of Rossy and Dixie Lee. The city also sits on a major highway and marks the beginning of coastal New Brunswick.

Over the Restigouche River estuary, a stately bridge connects Campbellton to Quebec. The history of the region is palpable on both sides. On the Quebec shore, the Mi’gmaq community of Listuguj speaks to the human presence that long preceded the settler world we see today. In the 1750s, the Baie des Chaleurs harbored Mi’gmaq and French refugees fleeing from the Deportation and the shocks of the Seven Years’ War. Only a short drive from the interprovincial bridge, we find the Battle of the Restigouche National Historic Site, operated by Parks Canada, which tells the refugees’ story.

While some people escaping the expulsion fled up the St. John or Wolastoq River, others found shelter deep in the Baie des Chaleurs, where they hoped to remain undisturbed. That window closed in 1760. The French crown sent a small squadron of ships in a woefully insufficient effort to dislodge the British from the St. Lawrence River valley. They moored temporarily in the Baie des Chaleurs. British vessels had spotted them and pursued them into the bay; they far outmatched the French ships. After giving battle with the help of Acadian refugees and Indigenous warriors, the French forces found they had no choice but to sink their own ships, lest they fall into enemy hands. Thus ended the reconquest of New France. As for the refugees, they escaped capture and surrendered following the surrender of Montreal in the fall of 1760. In Quebec, Governor Murray hoped to resettle the Acadians along the St. Lawrence. A small group chose to relocate. Those farther east, around the Acadian peninsula, faced belated deportation orchestrated by the Nova Scotia authorities.

The historic site’s museum is worth seeing not only for the story it tells, but for the artifacts salvaged from the bottom of the channel and its scenic location along the river. A smaller historic site at Petite-Rochelle and a beautiful coastal park near the interprovincial bridge deserve a place on any itinerary.

Along the Coast

From Campbellton, Highway 11 leads east to the Acadian peninsula. But the coastal road is preferable, at least from Belledune. The government of New Brunswick established a commercial port in Belledune in the 1960s. It notably served the Brunswick Smelter, a zinc and lead operation. Parent company Glencore terminated operations in Belledune in 2019, thus putting hundreds out of a job. Passers-by can still see the immense facilities in various stages of decommissioning and disrepair.

The Acadian world opens up a short drive farther on Route 134. Petit-Rocher proudly displays its heritage. Founded by the first generation of Acadians born after the Deportation, the town, like its neighbors, relied on the products of the sea, though seaside tourism has come to dislodge the fisheries as the premier economic driver. The park along the waterfront is a gem.

Between the Battle of the Restigouche and the founding of Petit-Rocher, a new chapter of Acadian history opened on the rocky coasts of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Governors like Michael Francklin made allowances for the resettlement or return of Acadian refugees, but almost never on the lands they had previously occupied. At the same time came entrepreneur Charles Robin, originally from the Isle of Jersey, who would become the “cod king” of the Maritimes region. While his brothers operated on Cape Breton, with an empire that stretched to Arichat, Charles Robin established his headquarters on the Baie des Chaleurs. His practices highlighted the mixed blessings of capital in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. His financial connections brought extra income to Acadian fishermen in his employ; on the other hand, the barter and credit system created a cycle of dependency. In other areas of New Brunswick, the influx of capital in the lumber industry had a similarly mixed legacy.

Though well within the Acadian region, some settlements speak to other cultures that helped shape New Brunswick. Bathurst—the province’s second-smallest city, for those who are keeping track—had been frequented by the Mi’gmaq; it was then known as Nipisiguit. This scenic area, surrounded by water, hosted the Acadians that went on to establish Petit-Rocher. Farther east we find Pokeshaw, which welcomed Irish Catholic immigrants from the 1820s to the 1840s. With its high cliff overlooking the bay, a view of the Gaspé peninsula, a sandy beach, trails, and a colony of cormorants, Pokeshaw is a guaranteed coup-de-coeur.

Caraquet and Shippagan

At last we reach the self-proclaimed capital of Acadia, Caraquet. Once a part of the Robin empire, Caraquet first made national headlines in 1875. The New Brunswick legislature had by then adopted a bill that established a common, secular system of public schools, to which many Acadian communities objected. In January 1875, a cycle of retaliation developed between those who favored and those opposed the law. Police and militia sent to quell opposition confronted alleged rioters in the Albert house. Gunfire erupted, leaving one militiaman and Acadian Louis Mailloux dead. The latter became something of a martyr and a monument now stands where the tragic melee occurred.

History is all around in the Caraquet area, much of it captured at the Village acadien in neighboring Bertrand. Other historic Acadian villages are open seasonally in Van Buren, Maine, and Lower West Pubnico, Nova Scotia. The Bertrand site is by far the largest. It includes about fifty publicly-accessible buildings, many of them staffed with reenactors—reenactors who have done their research, too. This traveler spent three hours there, but could have been on site for twice as long and still soaked in the experience (at least after a good soak in mosquito repellant).

Either as replicas or authentic constructions, the buildings range from the late colonial period to the postwar years. They cover different social strata and the commercial buildings represent different occupations: farmer, commercial fisherman, printer, tinsmith, etc. We find a mill, a schoolhouse, a church, a hotel, and a railway station. The whole journey makes for an invaluable glimpse into the material life of the Acadians of the peninsula, but also of other peoples in the transnational Northeast, who experienced the same material transitions. There is too much in the Village to recount here. Suffice it to say that, as with the other historic villages, it should be on any itinerary.

Shippagan lies at the edge of the mainland. Its waterfront includes an aquarium, trails, a small fleet of drydocked fishing vessels, and a monument to the Mallet and Duguay families that were the first non-Native to settle the area. Beyond, two major islands: Lamèque and Miscou, both scenic destinations in their own right.

Unfortunately, this cursory overview of the region fails to do justice to the sheer infrastructure that continues to make Acadian culture a lived reality, including the Université de Moncton campus in Shippagan, cultural venues big and small such as the P’tite Eglise, media like L’Acadie nouvelle and access to Radio-Canada, regular festivals, and the list goes on. This is in addition to the historic role of Catholic institutions. The diocese of Bathurst has had francophone bishops exclusively since the 1920s.

The Southern Section

Néguac had its own Acadian settlers in the Deportation era, the Savoies. But its development owed, more than a generation later, to Otho Robichaux, a bilingual repatriate who invested a small fortune in the area. He worked with the Robins and played a role not unlike that of Amable Doucet in southwestern Nova Scotia. He became a justice of the peace and the intermediary between colonial officials and the local Acadian population. Here too the fisheries have gradually given way to other sectors. The Ile-aux-Foins is home to a bird sanctuary and draws visitors through the warm season.

Finding new stability in the generations following the Deportation, Acadian families in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia then experienced a continuous baby boom throughout the nineteenth century. The discrepancy between population growth and economic opportunity would lead thousands to the United States at the end of the century. Religious and political leaders sought outlets; Rogersville and Paquetville, like Saint-Quentin, developed as agricultural outlets. Migration also occurred as a result of one of Canada’s worst natural disasters.

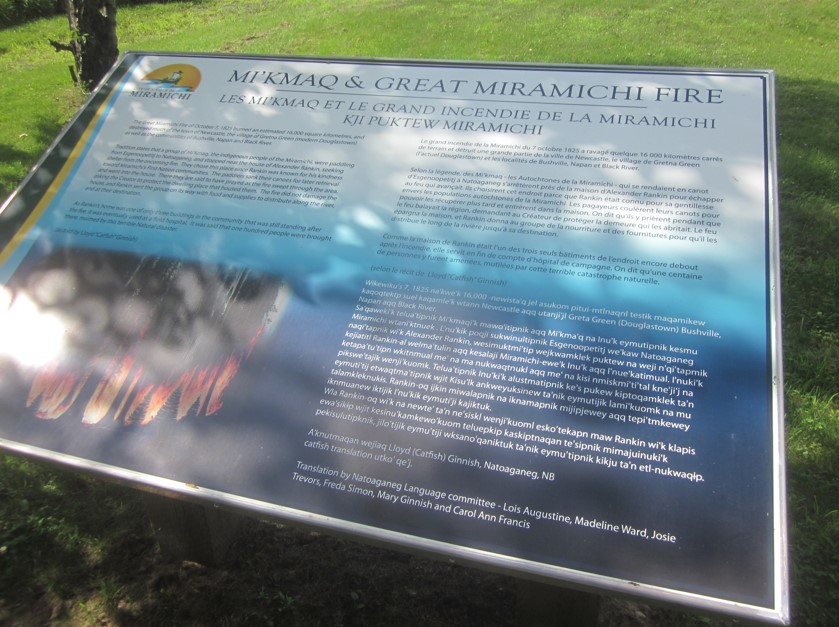

In October 1825, a wildfire erupted in the area west of present-day Miramichi. It swept quickly in several directions, reaching both Fredericton and Lower Caraquet. It is now believed to have been the third largest forest fire by area in recorded North American history. The exact death toll will never be known. Hundreds of homes were taken by the flames; an untold number of lumberjacks forever disappeared. People fled, some resettling in the Acadian communities along the coast. There would be little in the way of disaster relief of the kind we know today.

The present-day city of Miramichi sits, like other parts of New Brunswick, at the confluence of cultures. Mi’gmaq families took refuge there at the time of the great fire. Today it lies between the Eel Ground and Burnt Church reserves. As early as the 1840s, Middle Island, just downstream from the city center, served as a quarantine station for Irish immigrants. The region’s Irish heritage persists and, despite the presence of French speakers, the city is decidedly outside of Acadian New Brunswick. It is worth discovering for different reasons, including an attractive waterfront boardwalk.

From Miramichi, the return trip to Edmundston takes the traveler through perhaps the most remote area of the province. From its final junction with Route 8 to the first town, Plaster Rock, Route 108 offers a drive of an hour and a half, much of it without cell service and any sign of human settlement. A large span has no mile markers—and forget about gas stations or any feature not in the shape of a tree or a moose. In short, this is the kind of stretch where, as a casual traveler, you don’t want to have an adventure. Still, there is something in the experience, including remoteness itself and an appreciation for the sublime immensity of this wilderness.

From Plaster Rock, the little world of the Brayons is almost at hand. But the Upper St. John Valley and its distinct Acadianness merit their own profile.

A northern New Brunswick soundtrack for travelers:

- Roch Voisine, Avant de partir

- Edith Butler with Lisa LeBlanc, Dans l’Bois

- Tradition, Highway 11

- Denis Richard, Petit-Rocher

- La famille Leblanc, Suite des Iles

- Donat Lacroix, Viens voir l’Acadie

- Edith Butler, Paquetville

- Les Hay Babies, Néguac and Back

- Marc à Paul à Jos, L’Eléphant de Néguac

- Stompin’ Tom Connors, New Brunswick and Mary

- Mike Bravener, The Banks of the Miramichi

- Les Hay Babies, J’ai vendu mon char

Leave a Reply