The Canada–U.S. boundary is often represented as the longest undefended border in the world, symbolizing centuries of peace and amity between the two nations—or whatever Canada was prior to the twentieth century. As is often the case in history, this easy trope conceals a more complex and arguably more interesting tale—of which the current ban on non-essential traffic is but a small facet. For decades after the War of 1812, for instance, the threat of renewed conflict was palpable. Great Britain and the Great Republic each had cause to declare war on the other in 1838; with the end of the Civil War in 1865, colonists in British America feared that the American government would turn its armies northward. This is to say nothing of immigration, commercial disagreements, and security issues in less troubled times.

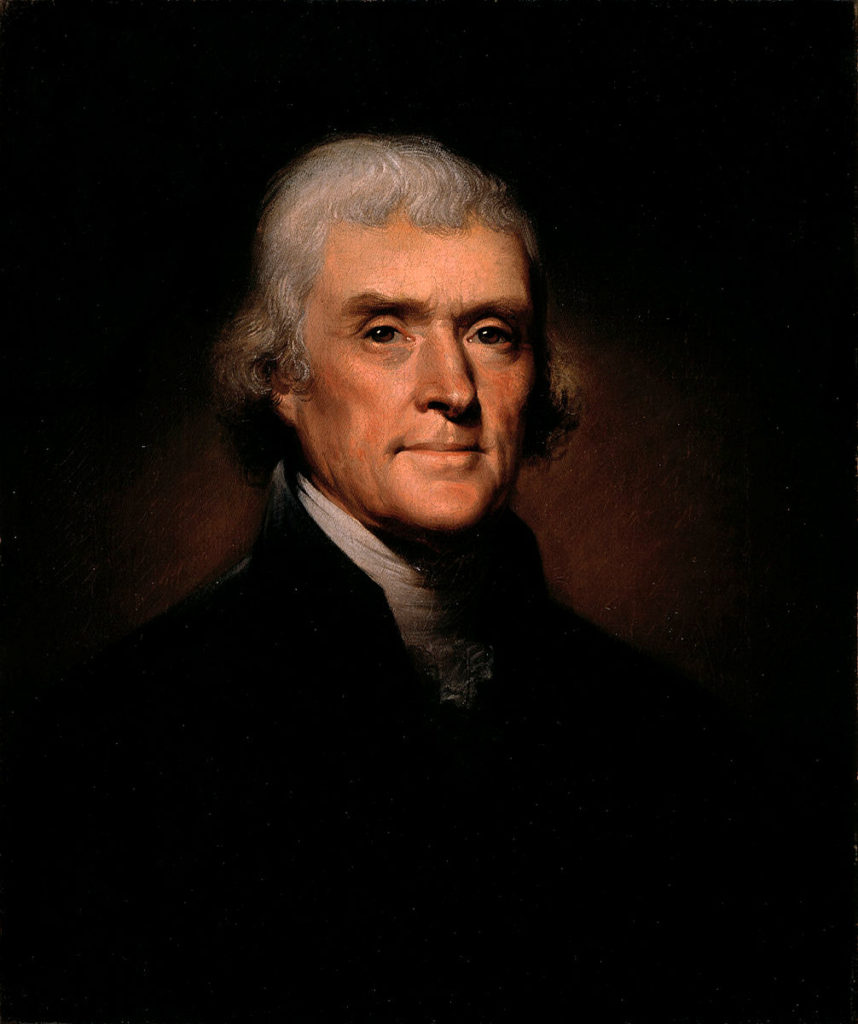

The first attempt to close the border to all commercial traffic exemplifies this rich, fascinating history. For that story, we have to return to the early years of the nineteenth century and to the escalation of Anglo-American relations over the dubious practice of impressment. Beginning in 1807, to exert pressure on Britain and assert American national sovereignty, presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison enforced an embargo on trade with Britain. Ultimately, the embargo had a much more detrimental effect on American citizens. It wasn’t merely the commercial class in seaports that suffered; expecting lost income, lenders tightened the money supply and called on farmers and tradesmen to settle their debts. Most New Englanders felt the bite of Mr. Jefferson’s embargo; some openly defied the law.

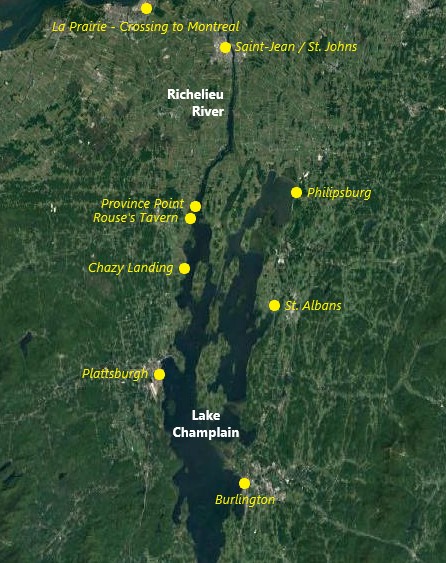

This was particularly true in communities along Lake Champlain whose natural outlets, thanks to the Richelieu River (which flows northward), were Montreal, Quebec City, and the larger British commercial world. Settlers living between the Adirondacks and the Green Mountains had found a ready, accessible market for their lumber and potash—the direct products of settlement activities on both sides of the lake—in Lower Canada. Even under the embargo, many merchants in the Champlain Valley expected payment from their counterparts in Quebec City. In these increasingly dire economic times, seeking to maintain their livelihood, Vermonters and New Yorkers were willing to risk their lives in potential gunfights with the loyal Jeffersonians enforcing the law from their sloops and customs houses at the north end of the lake.

There is another layer to the embargo era in the Champlain Valley. Until the War of 1812 and perhaps beyond, this was a borderland region marked by limited government authority and the meeting of various cultures. French-Canadian veterans of the War of Independence had been among the earliest permanent settlers of the Lake Champlain shore; they had received grants from New York State in compensation for their service. Those settlers did not suddenly disappear at the end of the eighteenth century; they remained and they were soon joined by kin and, after the War of 1812, by a rising tide of emigration from the parishes south and east of Montreal. The Champlain–Richelieu axis was in fact one of the earliest conduits of French-Canadian emigration to the United States.

One of the best first-hand glimpses of life along that corridor in the embargo era comes from Edward Augustus Kendall, who traveled through the region in 1808, as political tensions were quickly rising on the American side. Little is known of Kendall’s personal life; he left little trace of it outside of his writing, and even then we could not call him a major literary figure. We do know that at the time of his journey to Lake Champlain, in 1808, he was a published author of British birth aged about 30. His Travels Through the Northern Parts of the United States remains an informative look into the economic and cultural dimensions of this borderland region at a time when Britain and the United States were inching closer to war—and parts of New England, closer to insurrection. At last, the text helps us understand the nature of travel in early nineteenth-century North America, as this other travel narrative does.

An excerpt of the original text appears below in its unedited glory; the few additions, which provide modern spelling, appear in brackets.

“I had occasion to pass through this part of the country of Lake Champlain a second time, in the middle of the year 1808, and again in the beginning of that of 1809; and my journeys always threw me, either among those who were violating the law, or those who were endeavouring to enforce it.

“In June, 1808, I was two days upon the lake, making a circuitous voyage, between Saint-John’s, or Fort de Saint-Jean, and Burlington. The sloop in which I embarked, was one that belonged to the United States, and was liable to seizure, for having violated the interdiction; and was now employed in plying backward and forward, within the British dominion, receiving goods by stealth, and carrying them to Fort de Saint-Jean. Her master undertook only to convey me from the fort to the Province Point, a point of land so called, upon the west shore of the lake, in the forty-fifth degree of north latitude, and on which is set up a stone boundary-mark.

“Lake Champlain, from its heads, in Lake George and Wood Creek, to its discharge in the Saint-Lawrence, is only an expanded river, of which the extreme breadth is eighteen miles; and, at the Province Point, its breadth is only three.

“A want of wind kept us the whole day upon the river, and the sun was set when we were yet four miles short of the Province Point. It was now a perfect calm, and the captain, as I found, was not even desirous of further pursuing his voyage, perhaps because he had advanced far enough to take in new freight; but, to me, he gave for reason, that the custom-house officers were not at all too good to make seizure of his vessel within the foreign limits, should they know that she was so near them. Thus circumstanced, the anchor was dropped; and my prospect, of pursuing my journey, was brightened only by the appearance of a canoe, paddling from the mouth of the Lacolle. In the canoe were little boys, returning from the flower-mills on the Lacolle, and who engaged to carry me to the Province Point.

“With these pilots, I advanced two miles, at the end of which we came to land, in Odletown [Odelltown]; but, here, the boys were at home, and I found them but little willing to fulfil their bargain. Nothing ran in their minds, but that they and their canoe would be seized, should they venture too near the United States. On shore, however, I found a soldier, quartered in the place; and, having engaged him to be of the party, we again put forward.

“It was by this time dark; and all that diversified the scene, was the fishermen’s lights, which presented themselves in various directions. The inhabitants of these shores go out in canoes, in the head of which, in an iron frame, they fix a lighted pine-knot. The fish, attracted by the light, approach the head of the canoe, where they are struck with a spear, and caught. The large fish in the lake are salmon, salmon-trout, sturgeon, pike and pickerel. The effect of the lights, when they were near enough to the shore to be reflected by the trees, was exceedingly fantastic. In one instance, I believed, for some minutes, that I saw a mansion of large dimensions, with columns and with windows, and embosomed in the woods. There was nothing, in reality, but trees; and I thought that this deception afforded me some clew to the histories of those enchanted palaces, toward which knights, in black armour or in white, have turned their steeds, and which have vanished at their approach.”

This excerpt of Kendall’s journey across the border will conclude next week with encounters with French Canadians and outlaws.

Leave a Reply