See Part I here.

The Convention nationale des Canadiens français des Etats-Unis opened in Chicago on August 22, 1893. The event drew hundreds of delegates—though the attractions of the Columbian Exposition likely had something to do with their interest in attending. Exemplifying the incredible breadth of the French-Canadian diaspora, these delegates came from Langdon, North Dakota; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Fond du Lac, Wisconsin; Bourbonnais and Kankakee, Illinois; Manistee and Muskegon, Michigan; Toledo, Ohio; and many other locales between. The Northeast was also well-represented. Among its most prominent envoys were Fr. François-Xavier Chagnon, Connecticut organizer Omer Larue, and Benjamin Lenthier, who owned Lowell’s National and had recently become U.S. consul to Sherbrooke.[1] At Apollo Hall on Blue Island Avenue, site of the convention, mayor Carter Harrison—who would pass into tragic fame two months later—welcomed the attendees in their own tongue. It was all very auspicious.

Then came Mercier.

Having lost the premiership, the disgraced Liberal leader had embarked on a public campaign to free Canada from its colonial bond. Independence would erase past humiliation and provide new opportunities for French Canada, he argued. Annexation to the United States was not an ideal solution—at least not yet. Perhaps expecting a friendlier welcome abroad, Mercier spent the summer of ’93 stumping through Franco-American centers.

Press reactions were mixed. Some outlets were willing to extend the same courtesy he had shown Franco-Americans in the past. Others like La Presse argued that his “peregrinations” were sowing “elements of discord” on both sides of the border. They deemed him a charlatan who was struggling to draw audiences. (Aside from Hugo Dubuque, who welcomed him to Fall River, Massachusetts, his followers were depicted as grasping lackeys.) Such papers questioned his motives. Canadian independence was a matter to be put to Canadians, not expatriates. Was Mercier on tour simply to restore his finances or to prepare his political rehabilitation?

Those questions surfaced again as Mercier disembarked in Chicago. Though it had been a longstanding principle of national conventions to banish all explicitly political questions, the former premier might use the event to push for Canadian independence. It could also be—he was accompanied by L.-O. David—that he was consciously recreating the embassy of 1888. With the Conservative government failing to appoint good-will ambassadors, Mercier seemed to take it upon himself to affirm ties between Quebec and its diaspora. It’s equally likely that as his health began to fail, he hoped to restore his reputation—soaking up esteem and admiration wherever he could, while he could. (He died little more than a year later while still in his fifties.)

The event would not meet Mercier’s hopes. Let’s recall that this was a national convention of French Canadians residing in the United States, which Mercier was very much not. His passport to the event was a letter from a compatriot in Boston, the president of the local société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, nominating him as a delegate. Ahead of the event, Lenthier’s National questioned the appointment of Mercier. French Canadians who actually resided in Boston were available; it was in fact a poor precedent to appoint Quebec’s most prominent figures to defend Franco-American interests—the ideological vision expressed by the Quebec legislature highlighted the problem. Le National was conciliatory: it admitted that the Boston société was free to do as it pleased and that the selection should be judged by its outcome. The paper also recognized that Mercier’s was just one voice among hundreds. But, in advising against quarrels over this appointment, which might tear the convention apart, Le National also offered the surest way of avoiding conflict in the future:

We have enough to concern us in this country without having to worry about the fate of Canadians who’ve remained in Canada. If these people have half as much heart as those whom Providence has chased from their native soil, they will be well placed to manage their own affairs. Charity begins at home.

This was one of the many signs, in 1893, that French North America had fractured. Though faith, language, and culture might transcend borders, political boundaries were very real. Franco-Americans lived under different institutions, in an economy that was foreign in many respects, and felt the pressures of a mainstream culture that presented both promise and peril. They weren’t in Saint-Valérien-de-Milton anymore.

So, they had distinct concerns and interests and that was clear in Mercier’s reception. The credentials committee in Chicago rejected the ex-premier’s letter, which represented the wishes of a single person rather than the formal choice of Boston’s société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. Members of this organization had already appointed a delegate. Mercier returned to his hotel. Yet the debate was not over. That evening, friends of Mercier threw the matter to the whole body of delegates. According to one account, the ensuing debate ate up three hours of the convention’s time. Thanks to the vote of the local delegates, the stormy session ended in Mercier’s favor.

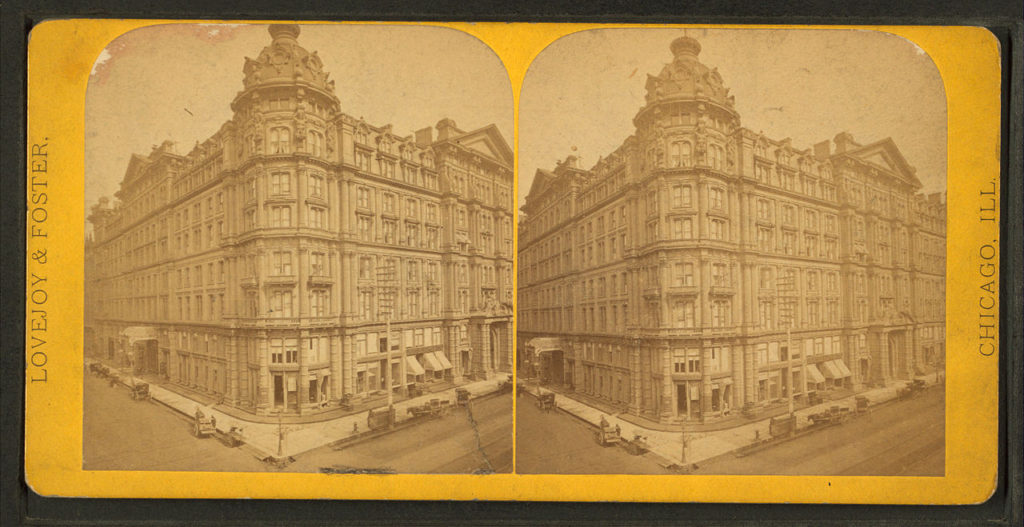

That was but a small consolation. Mercier was not among the list of speakers at the convention banquet held across the river at the luxurious Palmer House. He skipped the event altogether. Little more than an observer, with no place of particular honor, he left the city shortly thereafter.

And what of his travel companion? David attended the banquet in his capacity as president of Montreal’s société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. He had been among the few to shower Franco-Americans with compliments at the Montreal event in June. On the third day of the Chicago convention, he was invited to speak on the general situation of French Canadians; he stated that those living on the American side were better organized than their compatriots in Quebec. His presence still rankled certain delegates. An anonymous delegate’s account, printed in La Minerve on August 28, made that plain:

The executive takes no issue with Mr. David personally, but it had been decided, out of caution, to only invite to the convention Canadians in the United States, in order to avoid sparking American prejudice and reawakening concerns associated with Cahensly. One can be a true patriot, and stay attached to his faith and language, without parading his nationalism in an awkward manner that would be deemed treasonous to the nation that extends its hospitality. The Canadians of the United States, better acquainted with their own needs, believe that they can better manage their interests than their compatriots over the border would. Let each remain within the limits of their rights and duties and all will be well.

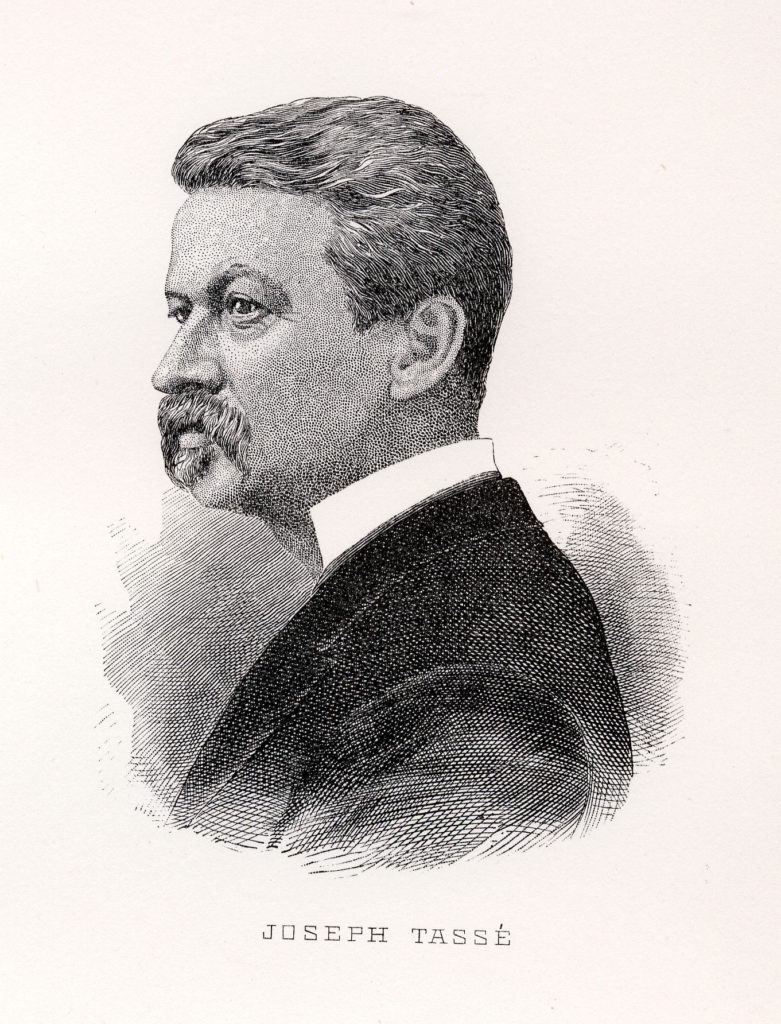

Predictably, La Minerve, edited by Joseph Tassé, published critical reports of Mercier and David’s presence. A Conservative in politics, Tassé had won election to the House of Commons in 1878 and earned himself a Senate seat in 1891. From this chamber Tassé was relentless in his investigation of the Mercier government at the time of the Baie-des-Chaleurs kickback scandal—the controversy that cost Mercier the premiership of Quebec. To say that the two men were political enemies wouldn’t capture the rancor and bitterness that separated them.

This should have been of no relevance to Franco-Americans gathered in convention. Alas, it wasn’t only Mercier who was summering south of the border. The government in Ottawa made Tassé its commissioner—in essence the lead Canadian representative—at the Columbian Exposition. In Mercier’s view, Tassé thus had the opportunity to turn opinion against him prior to his arrival. But there was more. The senator was invited to the French-Canadian national convention in August and held a place of honor at the banquet. Midwesterners thanked him for his Canadiens de l’Ouest, published some fifteen years earlier. Others remembered his outreach to expatriates in Lowell in 1882. When someone raised a toast to the old homeland, it was Tassé—basking in the absence of a certain Quebec politician—who answered.[2]

Thus, one last time, Quebec politics were exported to a French-Canadian national convention. And yet that was not the end of the excitement in Chicago. On the second day, prior to the banquet, a solemn mass held specifically for French Canadians and celebrated by Archbishop Feehan closed with a sermon delivered in English by the diocesan chancellor. Some delegates left the church in a huff. Mercier, always an unapologetic defender of his “race” when cultural slights arose, was among them. This walkout was much closer to the battles that awaited Franco-Americans specifically in the decades ahead.

As the two Quebec politicians left, delegates signed off on the habitual resolutions on naturalization, the preservation of the French language, and the utmost importance of Catholic education. They pledged to gather again in Fall River in 1896.[3]

The Chicago convention merits special attention because historians of Northeastern Franco-Americans typically overlook connections to the Midwest. The transnational dynamic is also important. In the 1890s, Mercier’s successors in Quebec City turned their backs on expatriates. That sentiment was increasingly reciprocated. By counting on Quebec’s support, Franco-Americans were opening themselves to feuds and political interests—even the cause of Canadian independence—that were not their own. That problem was impressed upon them, to the great annoyance of many, in 1896. It’s a story that has resonated for over a century.

All roads led to Chicago. To hundreds of delegates seeking self-determination, that was the problem.

[1] Lenthier’s appointment should remind us that 1893 was a big year in Franco-American politics. Nominations reflected a rising rate of naturalization; expatriated French Canadians were making the United States their home and getting noticed as a distinct voting bloc. Louis J. Martel launched his first bid for the mayoralty of Lewiston, Maine. He lost, but compatriot Aram Pothier, a future governor of Rhode Island, won in Woonsocket. In Worcester, Massachusetts, the Democratic Party nominated two Franco-Americans for common council seats, including the brother of L’Opinion publique editor Alexandre Belisle. Federal civil servant Edmond Mallet was saved from a partisan pink slip by a congressional ally and President Cleveland. Finally, Cleveland also rewarded Lenthier—but the consular appointment never received congressional sanction and the Lowell editor had to return home the next year.

[2] On August 29, L’Opinion publique sided with Mercier and stated that Tassé was the true fomenter of discord, creating conflict where there needn’t be. Mercier thought he was properly credentialed for the event and the organizing committee had formally invited David. The organizing committee, for its part, might have appeased partisan tensions by having both he and Mercier, a figure of far greater stature, answer the toast to Canada.

[3] In fact, without consulting the committee appointed in Chicago to organize the convention, certain figures of importance decided to make Woonsocket the host city. Nothing came of either plan. In February 1896, Philippe Boucher of Woonsocket wrote to his Midwestern confrère, Elie Vézina, that “there has been no talk of a convention. Should we ever decide to hold one, our friends in the West will be notified.” The founding of the Association Canado-Américaine at the end of that year presaged new means of upholding unity and ensuring communication outside of the national convention system.

My John F. Kennedy and the Politics of Faith is available from the University Press of Kansas. Consider buying from the publisher or supporting your locally-owned bookstore.

My second compilation of legislative debates on emigration and repatriation (1881-1900) is now available. Anyone interested in receiving a copy, in searchable PDF, of these debates can reach out to me either by using my contact form, by commenting below, or by communicating with me on social media or via e-mail.

Great article. Also, in 1900 another Franco-American fraternal organization was founded. L’Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste d’Amerique in Woonsocket, Rhode Island.

Initially it included Midwestern members grouped into councils. In fact, Elie Vezina became Secretary General, at the time the most powerful position with the organization.

The organization, a provider of life insurance and a promoter of Franco-American heritage, merged with Catholic Family Life Insurance, based in Wisconsin, in 1991. That company merged with Catholic Knights in Milwaukee in 2010 forming Catholic Financial Life.

The newest organization continues to promote some of USJB’s activities including a French-Canadian heritage Mass and event each September at the Shrine of Our Lady of LaSalette in Attleboro, Massachusetts.

USJB’s Mallet Library, named in honor of Edmond Mallet, is now housed at Assumption University in Worcester, Massachusetts.