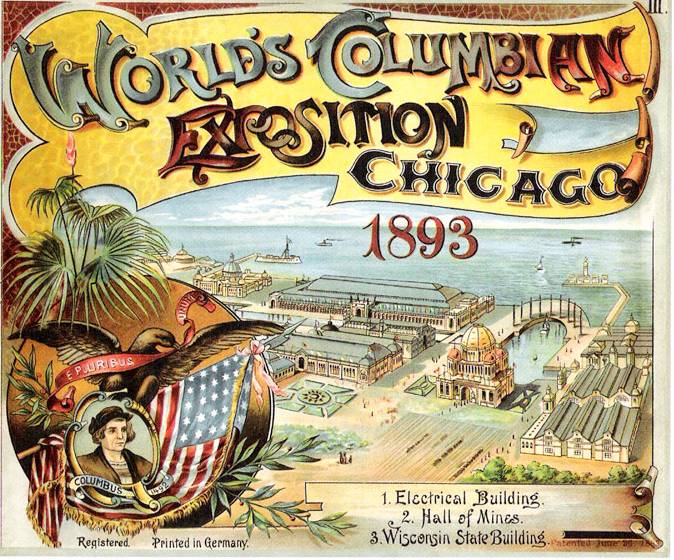

In the summer of 1893, all roads led to Chicago. The Great Republic was celebrating itself—or at least its white, colonialist incarnation—and the whole world was invited. The Columbian Exposition was to recognize four centuries of European settlement and achievement in the Americas and the United States’ own social and technological progress. All was not sunshine and spectacle, however—and not merely on account of the event’s racial dynamics. The fair was bookended by reminders of shocking, inexplicable violence. In June, in a high-profile trial that caught the attention of the Franco-American press, a jury exculpated alleged ax-murderer Lizzie Borden. In October, just two days before the fair’s closing ceremonies, a disgruntled office-seeker assassinated Chicago mayor Carter Harrison. Meanwhile, in major cities, working-class Americans could feel the early tremors of an industrial depression that would ultimately last three years.

The economic crisis did not keep people away. Many organizations went ahead with events that seized on the grandeur and excitement of the fair. In September, Chicago welcomed the Columbian Catholic Congress and the World’s Parliament of Religion. Newspapers reported that even anarchists would meet in convention in the Windy City. It should come as no surprise that Franco-Americans, too, gathered there during the long summer of ’93.

The last major Franco-American convention had taken place five years earlier in Nashua, New Hampshire. Delegates had at that time celebrated their common achievements and reaffirmed their dedication to survivance. Symbolically, Quebec’s provincial legislature had lent its blessing to the new lives and distinct communities that French Canadians had begun to create on American soil. A Franco-American identity was slowly forming. That was made quite clear in Chicago when delegates affirmed a kind of self-determination that was separate from Quebec’s destiny.

In the years following the Nashua convention, political events in Quebec helped deepen the fracture between French Canadians north and south. Premier Honoré Mercier, who had sent friendly envoys to Nashua, lost his office. In the wake of a kickback scandal, Quebec’s lieutenant governor dismissed Mercier and voters ratified the ouster. Under the incoming Conservative government, there would be no outreach, no expression of friendship and support to those now living over the border.

This should not strike us as unusual. Traditional elites had for some time argued that emigrants placed individual, short-term interest ahead of national and religious concerns. In 1893, under the latest Conservative ascendency, their view was fiercely propounded in three reports published consecutively. Public officials had commissioned reports on mass emigration since the 1840s; the latest one, with Conservative MLA Jérôme-Adolphe Chicoyne as the lead author, fell before the legislature in early 1893. Then came an unofficial report (in no less than 22 installments) published by the Conservative Courrier du Canada in the summer and early fall. Though first writing as “Beauregard,” the author finally revealed himself as Charles-Edmond Rouleau. At last, Télesphore St-Pierre, a former Michigander, published Les Canadiens des États-Unis; ce qu’on perd à émigrer. Three accounts, one story. All recognized to an extent the structural economic issues causing depopulation in Quebec. But, in tones reflective of the American Gilded Age, they also shifted responsibility to individuals. Emigration resulted from negligence in agricultural practices, mismanaged household finances, the inordinate pursuit of luxuries, and intemperance.

Franco-American elites were again in the treacherous position of defending their honor and legitimacy from nativist Americans, the working-class Irish, and influential Quebeckers.

Vindication might be found in Montreal, which, in June, was set to recognize its 250th birthday. (As with Chicago, it was marking the anniversary a year behind schedule.) The city would celebrate la Saint-Jean-Baptiste with pomp and then host a Congrès des sociétés nationales d’Amérique. Ahead of the event, L’Opinion publique, based in Worcester, Massachusetts, hoped Franco-Americans would attend this congress in substantial numbers; the exiles might thus challenge misconceptions about life in the United States and the conditions that had driven them over the border.

Delegates from Lowell, Massachusetts, did exactly that. Agricultural practice had little to do with emigration in the first place, they said. Quebec did not have industrial opportunities comparable to those of the United States and high tariffs limited Canadian farmers’ access to the American market. Joining the chorus were prominent visitors from other Franco centers: Fr. François-Xavier Chagnon of Champlain, New York; Dr. Valmore St-Germain of Fall River, Massachusetts; and Alexandre Belisle, editor of L’Opinion publique. Their plea was ignored. According to Belisle’s paper, “this congrès might not worsen our national situation, but, unquestionably, it won’t improve it. It has once again been proven that there are no worse enemies of the French race in America than certain French Canadians.”

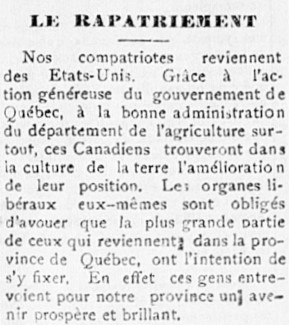

The discours de sourds worsened through those summer months. The economic crisis deepened and a wave of repatriation to Canada complicated discussions of French-Canadian mobility. The industrial Little Canadas were in fact hit quite hard from the early days of the downturn. As reported by Quebec City’s Courrier du Canada at the beginning of August,

A number of factories in New England have already suspended their operations as they are unable to move their merchandise out. In Lowell, Mass., the Pellings shoe factory has closed its doors and 250 workers are out of a job; in Ware, Mass., the Otis Company’s cotton mill, which employed 1750 people, has just suspended production; in Cambridge, Mass., the piano and organ factory of Mason & Hamlin has also closed; the Schuyler lighting company of Middletown, Conn., has reduced its week to five working days; in West Concord, N.H., the great Holden woolen mills have announced a weeks-long stoppage to begin shortly; in Woonsocket, we expect that in the next few days two of our most important industrial establishments will also shut down.

The government of Quebec claimed, to its own partisan advantage, that the much-maligned expatriates were taking advantage of its domestic colonization projects. In truth, many emigrants hoped the economy would quickly bounce back with production resuming at full capacity in early fall. In the 1860s, many French Canadians had seen their time in the United States as temporary; in 1893, in many communities, it was the opposite. Workers who went back to Quebec were very often waiting to resume their normal situation in the Northeast.

Through the uncertainty, through some families’ decision to return north, Franco-American pastors, printers, and professionals continued to defend their ability to live and thrive as French-Canadian Catholics under a different flag. Those leaders were undoubtedly eager to turn their attention to the Convention nationale des Canadiens français des Etats-Unis that would open in Chicago on August 22. Among their own, they would find a sympathetic audience; they would also attest to the flourishing of French-Canadian communities and culture across the United States. On the agenda were the preservation of the Catholic faith and traditional institutions, naturalization, temperance, and the prospect of a permanent, nationwide federation of sociétés.

Then came Mercier.

Come back in two weeks for the conclusion.

Pingback: Back-Page Americans: Clippings - Query the Past