Overwhelmingly, the hundreds of thousands of French Canadians who left their ancestral homeland in the nineteenth century were economic migrants. Most began their journey on American soil at the bottom of the economic ladder, an unenviable position reinforced by cultural barriers. The march towards middle-class status was typically multigenerational and marked by men’s ability to move away from low-skill physical labor and by women’s paid and unpaid work. That gradual ascent also occurred as new immigrant groups arrived and as Franco-Americans began to cross cultural lines. Exceptionally, some French-Canadian immigrants’ socioeconomic ascent could be meteoric.

Still today, both in Quebec and south of the border, it is a common practice to diminish the accomplishments of prominent French Canadians either because they do not represent the experiences of the entire group or because they seem to make too many concessions (cultural or class-based) on their way to success. But exceptional cases have long mattered for the representation and visibility they provide to ethnic minorities that seek cultural and political legitimacy.

In the Franco-American world, setting aside Aram Pothier and Paul LePage, well-known political success stories are few. That’s also true in business. The Aubuchons stand out; so does Joseph de Champlain, though in his case as either a charlatan or an incompetent. Other entrepreneurs succeeded—the Marcottes of Lewiston, for instance—but remain closely identified with their local community. One figure who deserves more than passing reference is Joseph L. Chalifoux, the Massachusetts businessman whose department stores made him a large fortune.

Chalifoux was born in Mascouche, then a quiet settlement north of Montreal, in 1850. His rural background should not conceal Chalifoux’s advantages. His uncle became mayor of Terrebonne; he was also related to future Conservative premier L.-O. Taillon. One article would later state that his father, also named Joseph Chalifoux, served in a judicial capacity—perhaps as a justice of the peace—in addition to his mercantile activities.

The younger Joseph attended a local collège classique and may have spent some time in Montreal afterwards. Naturalization records indicate that he settled in Lowell in 1867, when he was sixteen. He was certainly residing there at the turn of the 1870s; he obtained his citizenship papers in 1872, a fascinating break for someone who could have made much of his connections in Quebec. He worked as a clothing store clerk in his early years in Lowell—his parents had not sent him off with substantial means, it would seem.

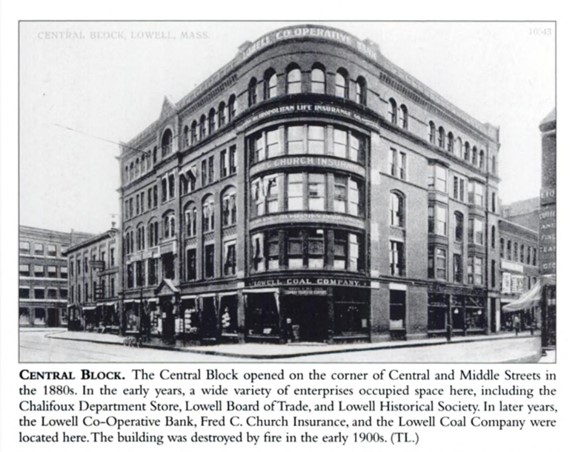

In his position, Chalifoux earned experience, learned about the local market, and likely refined his English. He launched his own clothing store in 1875. He had saved up in his time as a clerk, but it may also be that some family capital had come his way or that he had found well-placed financial backers in Lowell. Either way, he made the most of it. His store’s success no doubt owed in part to the then-novel policy of operating purely on a cash basis; in other words, there would be no store credit and no standing account, practices that assuredly caused the downfall of many retailers during the recession of the 1870s. After four years he moved to larger premises, and around 1883 he purchased the Central Block, located at the corner of Central and Middle streets. It became Lowell’s answer to Jordan & Marsh. The five-storey building was home to professional offices, including that of J.-H. Guillet, the city’s first Franco-American attorney. Chalifoux’s department store occupied the ground floor; it was “the largest clothing store in the state of Massachusetts outside of Boston.”

Like another immigrant and a fellow Franco success story, Hugo Dubuque, Chalifoux married the daughter of Irish immigrants. Ellen Chalifoux, née Gallagher, a former school principal, would bear six children. In the 1880s, good business enabled them to move from their home on Bartlett Street, just a stone’s throw from the factories, to a Greek revival mansion near the corner of Wilder and Princeton, on the outskirts of the city. By the mid-1890s they could afford to travel through Europe.

Joseph appears in the membership roster of a local Masonic lodge, which he would have joined in 1881 at the latest. That he was forging valuable connections is seen in his nomination to the board of directors of the Old National Bank in 1887. He became vice president of the Lowell Chamber of Commerce in 1891. By that time, he had expanded his commercial horizons significantly. While traveling through the South, Chalifoux and his brother Oliver had decided to launch a similar store in Birmingham, Alabama. According to contemporary reports, Joseph Chalifoux bought a parcel of land for $60,000, built a store at the cost of $100,000, and placed Oliver to lead operations in Birmingham. Another brother, Henry, worked there and the floor manager was a fellow French Canadian named St. Onge. “With pride they claim to be the only strictly one-price and strictly-cash house in the South,” a contemporary report declared. This store, too, seemed to thrive for a time. The Chalifoux clan moved it from its original premises to a new lot at the corner of First Avenue and 19th Street, across from the Opera House.

We get a closer look at Joseph’s personal approach to business in hearings held in Lowell, in 1899, by the U.S. Industrial Commission on Capital-Labor Relations (which included members of Congress). It seemed the Lowell store was coming out of the depression of the 1890s in a stronger position than before; the crisis had killed off smaller retailers and enabled entrepreneurs like Chalifoux to buy these stores’ stock at a discount. The sheer size of his operations also enabled him to deal directly with such local manufacturers as the Appleton and Lawrence mills. The textile industry was significant in another respect. When mills did well, so did his business. Chalifoux implied that factory workers patronized his store. It is reasonable to suspect that as their means grew, working-class French Canadians flocked to their compatriot’s attractive downtown location.

Chalifoux reaped the rewards. He supposedly contributed $50,000 to his daughter’s dowry when she married in 1903. At the time of his death, in 1911, the entrepreneur’s estimated worth was $1.5 million.

Come back in two weeks for the conclusion.

Very interesting loved reading it looking forward to next chapter