Surely we will all agree that transportation history is inherently interesting. If, somehow, we can’t, we should recognize that we can’t understand the history of commerce and migration without it.

We have previously seen (here and here) the challenges Bishop Plessis faced while traveling around the Maritime colonies and down to New York in the 1810s. Canal construction and the age of steam accelerated travel and improved communication—but did not always make for more comfortable travel. Over long distances, in the 1840s, better technology meant very little, as many Forty-Niners found out.

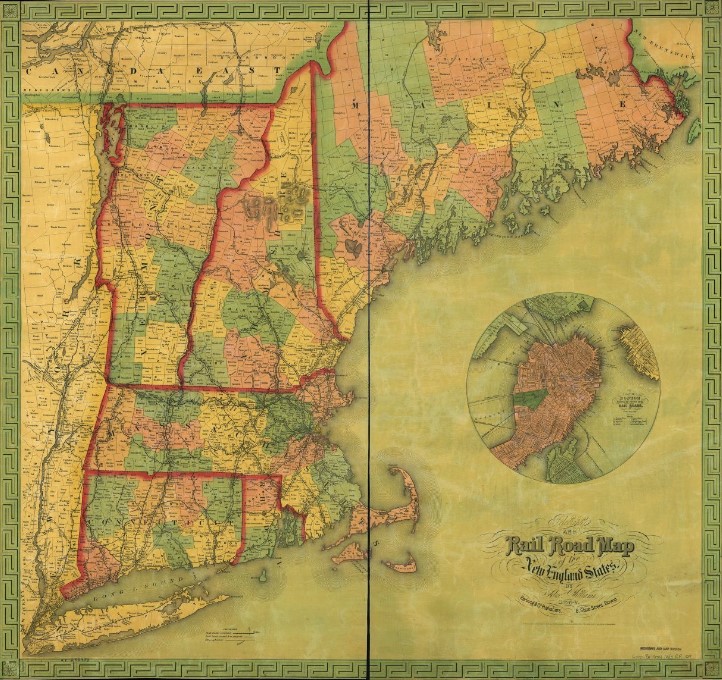

Nevertheless, in the Northeast, which boasted a large, concentrated population and a booming economy, steam power and advancements in transportation did yield tangible results. We might recall that it was a network of alternating railways and steamboats that brought Henry David Thoreau to Montreal and Quebec City in 1850. So it was in 1851, when hundreds of Canadian travelers left Montreal to visit New York City and witness Independence Day celebrations. Two railways and two steamboats made the trip possible. The prevalence of such excursions in this era shows how eager people were to discover different regions of the continent.

Noteworthy as evidence of growing cross-border connections, the 1851 excursion to New York also deserves attention for its political dimension.[1] The travel account below, penned by Jean-Baptiste-Eric Dorion, attests to the interconnectedness of Canada and the United States through infrastructure but also ideology.

Historian James G. Snell has argued that the bulk of community leaders in this nascent Franco-America were vocal critics of the Canadian government both before and after Confederation. They favored democratic reforms and greater autonomy for Canada, if not French Canadians specifically. It is unclear how widely shared these views were among the mass of ordinary immigrants. On the other hand, expressions of liberal-democratic fervor in the travel account below should not be read as pure editorializing.

Dorion, the author, was the general manager of L’Avenir, a newspaper that constantly challenged the moderate, conciliatory impulses of the Lafontaine-Baldwin government and its successors. His own brother was a leader of the so-called radicals in the Canadian parliament. The excerpted letters suggest that Dorion found a likeminded professional and commercial elite south of the border; his was an infatuation with the United States that also manifested itself in a strong annexationist movement.

The following excerpt is a translation of Dorion’s letters, which appeared in L’Avenir on July 9 and July 18, 1851.[2] Seeking to provide the essentials, I have condensed certain passages in brackets and omitted more mundane information—for instance, the list of people who subscribed to the flag project. I encourage everyone to read (and read around) the original texts in French.

* * *

After the storm, the calm returns. For most of us Canadians[3] who traveled to New York City to attend the great celebration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of American independence, the day of July 4, 1851 was a veritable storm—a happy storm, certainly, if we are to judge by the immense clamor and the sound of unanimous rejoicing from a nation that cherishes its liberty . . .

Departing from Montreal on the morning of July 2, our group numbered 325. We had a beautiful day. We could see the full expanse of Lake Champlain and, as we gaily amused ourselves, we attracted the curiosity of the strangers on board from the natural simplicity of the lyrics and the happy style of our French-Canadian songs.

After sitting for dinner, excursion participants came together on the ship, the United States, and the following proceedings took place . . .

[The small assembly elected P. E. Leclerc of Montreal as its president and resolved (1) to offer a flag[4] to the Canadian benevolent society of New York during its July 4 activities; (2) to thank George Batchelor and his collaborators for their role in organizing this excursion; and (3) to submit these proceedings for publication in the French and English newspapers of New York City.]

This assembly disbanded. We reached Whitehall [at the southern tip of Lake Champlain] in time to take the [railway] cars at 6:30 p.m.; at 10 o’clock, we arrived in Troy, surprised to find a crowd that followed us and that extended a welcome to the sound of drums, trumpets, firecrackers, and who knows what else. French-Canadian voices also greeted us. Though planning to go to our hotels, we were swept up towards the public square where a bonfire lighted the faces of at least 2,500 to 3,000 people. A band played as best it could under the guidance of our compatriot, Mr. Rodier. Mr. P. Griffard read a heartfelt and fraternal address penned by the French Canadians of Troy,[5] to which MM. J.-B.-E. Dorion, J. Fortin, and G. Batchelor responded on behalf of the Canadian excursionists.

Then, Troy’s mayor stepped forward and, in brief remarks filled with sympathy and liberality, communicated the city council and residents’ sentiments. He was pleased to welcome the Canadians, though he regretted that we would be departing so quickly, for he would have preferred to greet us more formally the following day. He invited us to stay.

MM. J. N. Willard and A. Millard also spoke and the latter delivered a fine address about the United States, Washington, and Lafayette, names that are inseparable and that schoolchildren learn to revere. Millard complimented French Canadians as descendants of Lafayette’s homeland. He spoke of independence and the American union, declaring that Americans would be ready to admit us as brothers to their state of prosperity, happiness, and liberty, and that they would help us traverse the inevitable difficulties of separation from England . . .

On Thursday morning, we boarded the Reindeer to travel down the Hudson River to New York City. The skies were clear and the water, limpid. The trip was meeting with general satisfaction when a small accident forced a stop at Oakhill, where we were detained for two hours. Still, when we arrived here [New York City] at 7 p.m., committee members from the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste were awaiting on the dock. We shook hands cordially and we dispersed towards our hotels, most of us going to French and Lovejoy’s . . .

Yesterday morning [July 4], all of the shops were closed except for barbers and dealers of firecrackers, rockets, and other such items. Let’s not talk of all these things, but instead discuss the Canadian excursion. The Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste of New York formed itself for the procession and called on us. The excursionists paraded two by two with the banner they aimed to present to the Canadians of New York; the latter joining us, more than 200 of us marched. The procession, organized at French’s Hotel, traveled Chatham Street [now Park Row] and Broadway down to the Battery. There it paused under the park’s beautiful trees. We cannot say how many thousands of people assembled around this small reunion of Canadians to see what would happen next.

Gabriel Franchère, Esq., president of the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, addressed the Canadians . . . The Société took possession of the flag and, at the head of our procession, led us down Greenwich and Cedar streets and the park to City Hall. Thence we went to French’s.

All the time that our orators spoke in French, in the public places of Troy and New York City, thousands of people who didn’t understand a word of their remarks listened in respectful silence. I believe this is worth mentioning; it says something of the tolerant character of the American people. National feeling finds protection in this land of liberty.

[After returning to the hotel, the Canadians were enjoying refreshments when members of the Tammany Society invited them to join the Independence Day celebration, where else, but at Tammany Hall, just a few steps from City Hall. The Canadians happily consented to the invitation. Members of the expedition were free to roam as they pleased on July 5.]

As per earlier arrangements, approximately 150 gentlemen and 50 ladies left the city at one o’clock in the afternoon on July 6. We rode the railway to the village of Harlem, some three miles from New York. The planning committee for this event had spared nothing to make it as pleasant as possible. An excellent band greeted us with melodies that tickled the French-Canadian ear. The table had only been prepared for a hundred guests, however, and our host was discouraged to see us arrive in such large numbers. This was Sunday, which, in an American village, meant we wouldn’t be able to procure any more food than we had in the house. We had to make do with that which had been ordered.

[Dorion then shares the proceedings of the banquet as first published by New York’s Herald. Toasts celebrated, in order, Canada, the United States, France, Josephte (the French-Canadian woman), and the free press. Dorion was invited to speak; he raised his glass to expatriated Canadians.]

I am persuaded that all those who took part in the banquet will never forget the delightful hours they spent in Harlem on July 6. On Monday, the excursionists visited Brooklyn, Greenwood Cemetery, Hoboken, Staten Island, and the outskirts of New York. At the end of the day and again this evening, many chose to return to Canada. I am just back from Hoboken where, with many friends, we partook in a picnic organized by Mr. Masseras of the Phare de New-York,[6] a perfect gentleman in every respect, with whom we spent pleasant moments . . .

I believe a great deal of good will come from this trip. It will help dissolve preconceived notions on both sides—it has already quelled prejudices of giant proportions. Let us hope, then, that events like this will become frequent, for they will educate us, and we have much to gain from contact with an intelligent, enlightened people that knows how to defend and uphold its civil and political rights . . . I have often longed for the day of our emancipation. I believe that day is approaching. It could not be otherwise. The radiant stars of the American union will eventually shine over our poor country still shrouded in darkness. Let it be so.

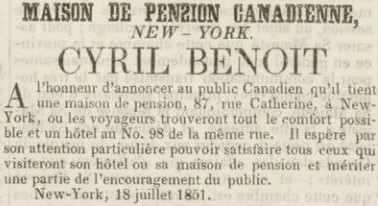

[1] New York City was the site of the first société Saint-Jean-Baptiste in the United States; its history has been traced by Jules Jehin de Prume and Antonio Fitzpatrick. The city would also host the first “national convention” of French Canadians in the United States; delegates met at the St. Charles Hotel in November 1865. With New England’s immigrants still relatively unorganized from the perspective of community institutions, and benefitting from only a tiny middle class, it is no surprise that all but one of the convention officers elected by the delegates in 1865 resided in New York State.

[2] Shorter accounts also appeared in Lower Canada’s English press, e.g. in the Montreal Herald on July 12 and the Quebec Mercury on July 15. The second is particularly delightful. A group of travelers from Quebec City was supposed to meet George Batchelor’s participants in Montreal, wherefrom they would set out together. Delays on the river prevented a common departure. The Quebec excursionists continued, but they were a day behind the main group. One can sense the very human frustration about this missed rendez-vous that would be felt as sincerely nowadays. Like Dorion, the author of the Mercury account praised the healthy effects of such trips on British and Americans’ views of one another. He supported more of these “friendly invasion[s].”

[3] In his letters, Dorion referred to participants as Canadiens, a term he may have used in an ethnic sense, but there is no reason to believe, from extant evidence, that people of British and Irish descent did not also take part in this organized excursion. Accordingly, my translation prefers the more inclusive “Canadians.”

[4] Dorion later describes the flag, which was designed by a Mr. Goulet in New York. One side depicted John the Baptist, bearing a wreath of maple leaves, in the Jordan River. A beaver and its dam, also surrounded by maple leaves, appeared on the other side. Inscriptions indicated the donors—the excursionists—and the recipients and listed the date of the event.

[5] Griffard expressed an emotional connection to Canada. He saluted the political institutions of the United States and the hospitality with which migrants had been received. He hoped Canada would soon be freed of its colonial shackles. Thus Griffard celebrated not only the actual independence of the United States, but the hoped-for emancipation of Canada.

[6] Masseras was a native of France. New York City’s francophone press was then in the hands of France-born individuals rather than French Canadians, though it did carry items about the latter.

Leave a Reply