It all starts with inconvenient, even provocative questions.

If we believe that history truly matters—whatever our reason for saying so—we must surely agree that historical truth matters.[1] That truth is rarely tangible or instantly accessible. Our awareness and understanding of past events are molded by our memory, our values, and the natural limits of popular culture and public education. There is more, however, to history than entertainment and the formation of obedient or engaged citizens; more to the past than what we imagine it to be or would like it to be. The past is always more complex than we suspect and, to access it, we need good history.

“Good history” is captured in the original meaning of the word, the Greek historia: an inquiry. That is to say that history is an intellectual activity that seeks out the truth about the past. It is an investigation that begins with inconvenient, even provocative questions.

Granted, history operates in an ever-changing social setting, to which it responds. “It’s based on what’s going on around us in the present day, and what our present concerns are,” historian Daniel Francis explains. “This is why history is always changing. Sometimes, people get the sense that there is ‘a’ history, and it exists, and it’s your job to find it. But of course there isn’t. It’s changing all the time. Our interpretation of the past is changing all the time, due to the questions we ask of it.”

New questions, yes, but also different sources and better methods. Since the past itself does not change, all of this leads to a better-rounded, broader, and more precise field of knowledge.

This may seem mundane and, arguably, it should be. However, recent battles over the Confederate monuments, the “canceling” of Columbus, the 1619 Project, and critical race theory have exposed the fraught terrain of historical investigation. Provocative questions and unpleasant answers are often rejected out of hand, particularly if they fail to conform to our collective memory—our established narratives. Yet, as Dan Rather and Elliot Kirschner argue in “History Is Not Comfortable,” we are not prepared to face the legacies of the past in the present day if we do not tell the full truth about that past. “Those who seek to keep our history classes the realm of comfortable fairy tales rather than hard truths are not trying to wrestle with the past in good faith,” Rather and Kirschner state. “They don’t care about what really happened. They don’t want to know about it. And they don’t want anyone else to know about it either.”

Nowadays, the term woke is used as the ultimate term of disparagement of “alternative” or inconvenient history. No further discussion needed: it is woke, therefore not serious. We can brandish the word without having to even engage with the ideas. And yet, Godwin Smith might have deemed the French-Canadian literary revival of the 1860s and 1870s a “woke” movement. We can certainly imagine how conservatives would have made use of the term at the height of the civil rights and women’s liberation movements.

Francis agrees with the other authors’ assessment. “I guess, at certain points of time, it seems that if you’re reinterpreting history, you’re somehow attacking the country, attacking its notions of itself. This is a position that I don’t agree with, but apparently this is a position that many people hold—that we can’t have a complicated history.” We might add this applies not only to countries, but to ethnic, racial, religious, and linguistic groups that have their own supposedly unassailable narratives—and that bristle when new research is undertaken.

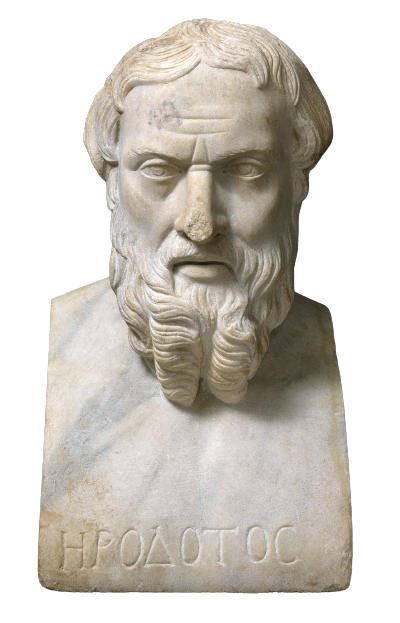

As is often the case, Ancient Greece gives us the archetypes: Homer, the bard to whom we have attributed the Iliad and the Odyssey, and Herodotus, whose Histories captured the cultural landscape of the eastern Mediterranean and the context of the Persian Wars. Homer communicated stories that were handed down because they were useful narratives. They bolstered existing Greek self-conceptions. Herodotus traveled widely to collect testimony from different sources and challenged Greek myths, including the belief that theirs was the most ancient society in that part of the world. Well, history à la Herodotus would succumb with Antiquity.

A small revolution in historical practice occurred in the early modern period as thinkers wrested the past from religious and political hagiographies and the medieval chronicle. Elites drew from the past a guide to moral, legal, and political action. Yet this was an essentially celebratory history—often because these historians (if we use the word loosely) were, as their predecessors had been, dependent on structures of power and had a stake in upholding them. Those who were meaningfully investigating the past were antiquarians with far less clout.

The rise of history as a distinct discipline in universities—which were better shielded from political, economic, and popular pressures—changed the game. This new space opened greater freedom to challenge well-entrenched tropes about the past. Academic history would henceforth have its own arc alongside histories that had to be suitable to established institutions and to popular audiences.

The chasm between these approaches to the past has widened considerably in the last fifty years.

Academic historians have not been alone in expanding the slate of historical “facts,” some of which had to be unpleasant and inconvenient, seeing the endless complexity of human behavior. These academics have earned special enmity, however. A populist undercurrent that is suspicious of the ivory tower (“I don’t need Professor Egghead to tell me what to think”) is not hard to find. But other fields have been protected either because they offer students well-defined professional outcomes or because—like the theoretical sciences—they are deemed to have a method and to be objectively measurable.

Academic historians strive to reach ever-wider audiences, though more could be done to help communities see the evidence and understand how history, as a field, works. More could and should be done to explain the historical method and the checks and balances that lead to better history. When scholars offer interpretations that go beyond that which the sources will allow, their peers waste no time in letting them know. Over time, good history tends to drive out bad. If this seems a little too triumphalist, that good history must still be in conversation with popular memory and respond to the preoccupations of the day.

There are still some critics, as there may forever be, who see political and social engagement on the part of historians (who, ironically, are coming out of the ivory tower) as a smoking gun. Biased! they will cry out, as if some human beings somehow lived outside of space and time. That is often the first trap in university students’ historical analysis and it comes impressively close to an ad hominem argument. That argument also has the convenient virtue of moving the conversation away from the actual work—sources, method, interpretation.

This applies to all fields and subfields of history. And this blog being what it is, we have to hope for continued research on transnational French-Canadian history and the inconvenient, even provocative questions that will connect us with the past as it actually was. As always, that complex past will broaden our horizons and expand the world we are able to view.

[1] I have offered a few modest reasons to study the past on ActiveHistory and on this blog.

Leave a Reply