Quebec historians and mythmakers have accorded a lot of attention to Lord Durham, the governor who spent five months in Lower Canada in 1838. Today, he might be remembered for granting a broad amnesty to people implicated in the first rebellion, if remembered at all, were it not for the report he submitted in Britain the following year. Two excerpts in particular have been repeatedly quoted. He stated that he had found “two nations warring in the bosom of a single state,” a conclusion that some nationalist historians have accepted. Also, Durham deemed French Canadians “a people with no literature and no history”; with that, the British bird of passage formally entered the annals of Quebec history as bugbear and personification of outside threats. It mattered little, to later writers, that history in Durham’s sense meant a branch of learning and that the first novel in Lower Canada, L’influence d’un livre, only appeared in the fall of 1837. Equally forgotten were the former governor’s rejected proposals, including responsible government for the British North American colonies. This is not to put Durham on a pedestal, but quite the opposite. In the larger arc of Canadian history, he was a fairly inconsequential figure.

On the other hand, we have a figure who benefits from no name recognition whatsoever, but who molded the course of events in Lower Canada, in the 1830s, more than anyone else except for Louis-Joseph Papineau. That man was Charles Richard Ogden (1791-1866). Louis-Georges Harvey and Yvan Lamonde’s recent Une lecture impériale de la résistance de 1837 et de sa répression: le rapport Ogden (2023) sheds light on Ogden, his times, and the part he played in all manner of legal and political affairs in the Rebellion era. Whereas our historical eye has long been trained on Durham, in many respects it is Ogden’s story that tells us the most about the events of 1837-1839.

The son of a Loyalist, Ogden was admitted to the bar in 1812 and elected to the Lower Canada House of Assembly two years later. He served as a leader of the “Bureaucrat” party. He became solicitor general of the colony in the 1820s and attorney general in 1833. A year later, the Parti patriote adopted the Ninety-Two Resolutions. The party thereby denounced a colonial system that had frustrated the goals and vision of the elected representatives in the Legislative Assembly. It also denounced what it deemed to be the partial, corrupt, and undemocratic rule of the governor in addition to the unaccountability of public officials. Beyond the resolutions, as a pressure tactic, the Patriote-dominated Assembly stopped funding the salaries of appointed officials in the colony and blocked a variety of commercial policy proposals, thus undermining insofar as it could the normal business of government.

London responded to the resolutions by sending the “3G” commission of inquiry (Gosford, Gipps, and Grey). In light of the commission’s report, in the spring of 1837, the government adopted the Russell Resolutions, which amounted to a general rejection of the Patriotes’ demands. News of this rejection soon reached North America and so began the steady march to open rebellion. Opponents of the regime organized mass rallies that often turned seditious. Leaders of the Parti patriote flirted with revolt. Charles Richard Ogden did not merely have a front-row seat. He was, short of Lord Gosford, the highest-ranking official charged with the preservation of law and order across the colony.

Harvey and Lamonde’s work provides a strong overview of the breakdown of order and the legal context surrounding the Rebellions as seen by the attorney general. By the fall of 1837, as violence erupted on the streets of Montreal and rumors of armed resistance floated from the Richelieu basin, a legal response seemed necessary. Ogden moved his office from Quebec City to Montreal and approved arrest warrants for 26 individuals involved in fomenting dissent, among them prominent Patriotes. Resistance to these arrests led the colonial government to seek the assistance of military forces. Outright battles ensued.

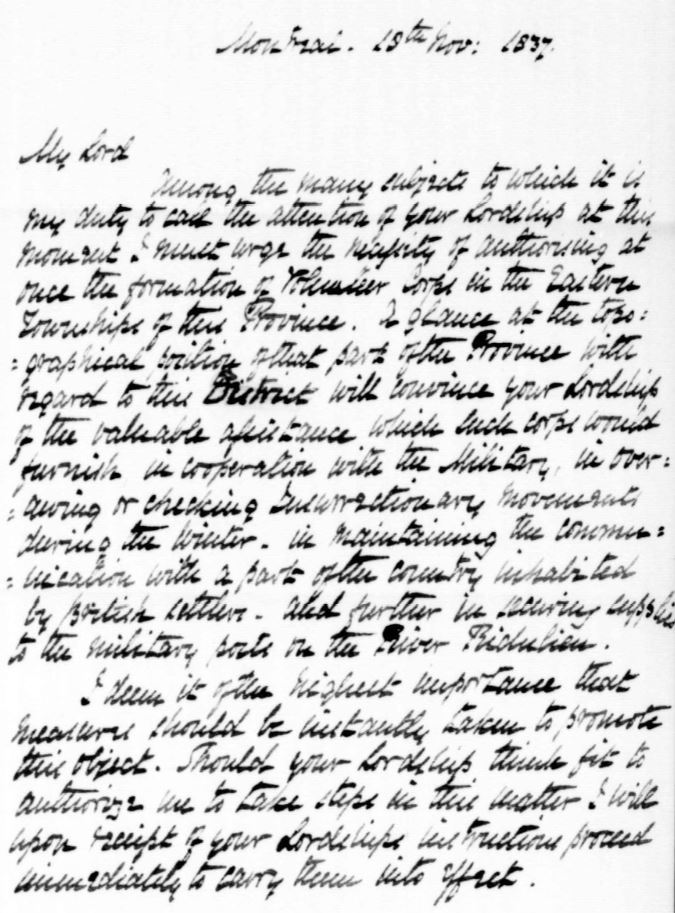

We easily forget that even while military operations unfolded, the Rebellions created an immense amount of documentation: affidavits, cautions, court proceedings, depositions, suits, testimony, and warrants in addition to correspondence and a larger number of local reports. Ogden was at the center of this exploding archive, enabling him to assemble a large dossier on disloyalty in the colony.

In the spring of 1838, General Colborne, now administrator of the colony, released more than 300 prisoners accused of high treason. He thus followed the British government’s advice to prosecute only the ringleaders of the insurrection. That did not do away with the need to prosecute criminal acts. In this regard, Ogden was confronted with the virtual impossibility of guaranteeing fair trials in some areas. Some active agents of rebellion would be exonerated by sympathetic French-Canadian juries. Such a fate seemed to await the men accused of the shocking murders of a British lieutenant and a loyal French Canadian from Saint-Jean.

Ogden’s lengthy experience in government proved a personal asset; the quick succession of governors and administrators—Gosford, Colborne, Durham, Thomson—also momentarily enhanced his profile. While Colborne was emptying the jails of Montreal, he, Ogden, penned an extensive report on the situation of the colony that has long been buried in Quebec archives and that forms the heart of Harvey and Lamonde’s work. Whereas Durham’s report charted a new direction for the twin colonies of Upper and Lower Canada, Ogden’s—written six months after the battles of 1837—focused on the more mundane but arguably more important matter of maintaining peace, order, and good government where all three had broken down and where much of the population remained disaffected. This is not to say that Ogden did not have his own partisan blinders. He wrote, for instance, that

human experience cannot recall any instance of a people of whom so much good will had been expressed, and upon whom so many benefits had been lavished – who lived in daily and uninterrupted enjoyment of happiness and prosperity to which European communities cannot aspire – who felt no practical grievances – who could anticipate no probable wrong – having been deluded by theories they could not understand to clamour for organic changes they could not appreciate or attempt to enforce their intemperate demands by a reckless appeal to arms. (151)

Lord Durham, who reached Quebec in May, and his entourage initially kept Ogden at bay. They hoped to steer a middle course and avoid the sway of both the Patriotes and the Loyalists. A gradual convergence of positions occurred, however, especially after Durham met Montreal Tory leaders. (He was nevertheless critical of Tory leaders and institutions in his report.) Durham issued his broad amnesty in June 1838; his Special Council adopted consequential legislation. But it was all a blur: the governor announced his resignation in October. The next month, rebellion was again at hand. Authorities would prove much less lenient this time.

Charles Poulett Thomson, the next governor, confirmed the attorney general in his role. Ogden was ultimately unhappy with the diminished salary and new political landscape. He took an extended leave of absence in England. When he returned to the St. Lawrence Valley, he found that Louis Hippolyte Lafontaine—imprisoned in November 1838—had been appointed attorney general for Lower Canada. Ogden left again and spent the last twenty years of his life as a high-ranking official in the British Isles.

The report that Harvey and Lamonde have resurrected resonates in many ways. The issues that Ogden confronted in the Rebellion era are still relevant today, including efforts to defund government, the intimidation of office holders, and the challenge of prosecuting political prisoners. How should legislators respond to a breakdown of law and order? How should they navigate freedom of speech as well as the threat of radicalization? What is the right balance between conciliation and punishment? Ogden’s report may not offer a perfect roadmap to present challenges, but offers a way of thinking through them—as well as helping us approach the Rebellions from a new angle.

Une lecture impériale de la résistance de 1837 et de sa répression: le rapport Ogden is available from the Presses de l’Université Laval.

Excerpt

On the 26th of October two days after the meeting of Saint Charles, Dr. [Charles-Hector-Octave] Côté of Napierville in the County of Acadie, of which he was the representative in the House of Assembly, returned to Blairfindie accompanied by Mr. François Ranger, Louis [Denoyer], a notary of that place, Julien Gagnon, Olivier Hubert, Jacob Bouchard and a gang of desperadoes and immediately commenced a warfare of compulsory resignation by demanding the surrender of the Commissions of the Peace held by Dr [Timoléon] Quesnel of Blairfindie and Laurent Archambeault esquire of Acadie. On the following day Mr Dudley [Hobbes] of Saint Valentin was in like manner summoned to throw off his commission of Lieutenant of Militia, Captain Pierre Gamelin, Captain Louis Bessette and several other officers of Militia and loyal subjects were subjected to similar requisition. Many from the numbers and manner of the mob were intimidated into an immediate surrender of their commissions. Côté boasted that in the course of a few days he had extorted in this manner upwards of sixty. Others who more resolutely resisted impertinent dictation were exposed to the annoyances and damage of a Charivari. A mob of armed men, masqued and disguised, assailed their houses in the dead of the night and by discharging their fire arms and blowing horns and yelling imprecations and by the more alarming demonstrations of dashing in the window shutters with clubs and throwing heavy stones through the roofs, compelled the proprietors, moved by the distress of their terror-stricken families, to yield a reluctant consent to their demand. Messieurs [William] McGinnis of Acadie and Loop Odell of Napierville, both magistrates were forced in their isolated and unprotected condition to submit to similar intimidation . . . A mob of charivaristas attacked the dwellings of a peaceable community of Baptists in the parish of St Valentin, and by expressions abusive of their peculiar persuasion and other violence compelled many respectable families to fly for safety into the contiguous state of New York. The system of terrorism had not however confined itself to the County of Acadie. At St Césaire and La Présentation in the County of St. Hyacinthe. At Chambly, at Ste Marie de Monnoir in the County of Rouville and at the Seigneury of Sabrevois where Messieurs Chaffers, Cazavant, Lemay and others had rendered themselves obnoxious by their uncompromising loyalty and generally through the parishes of the Six Counties wherever any reluctance to comply was exhibited (and it was of very infrequent occurrence) the resignation of all officers under the government was peremptorily insisted on. (146-147)

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - February 1, 2025 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte