In conversation with Claire-Marie Brisson of the North American Francophone Podcast, several years ago, I introduced the concept of “back-page Americans,” which applies to many historically marginalized groups. In the context of Franco-American history, the concept grows out of the seeming invisibility of French Canadians in the mainstream (i.e. non-ethnic) American press. In reality, immigrants and their immediate descendants often appeared in newspapers, but found themselves relegated to short articles and briefs that did not identify their ethnicity or, very often, place of origin. As a result, we miss these individuals and their stories if we only scan for articles on their ethnic organizations or on immigration from Canada.

The concept is especially valuable when thinking of the geographical and cultural margins of Franco-America. In such places as Woonsocket, Fall River, Lowell, Manchester, and Lewiston, by virtue of their population, we need not look far for references to French Canadians and their community organizations, even in the English-language press. But, in smaller communities, especially in the earliest fields of migration, the back pages are precisely where they are to be found—even if a French surname is all we have.

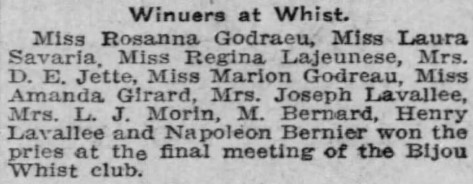

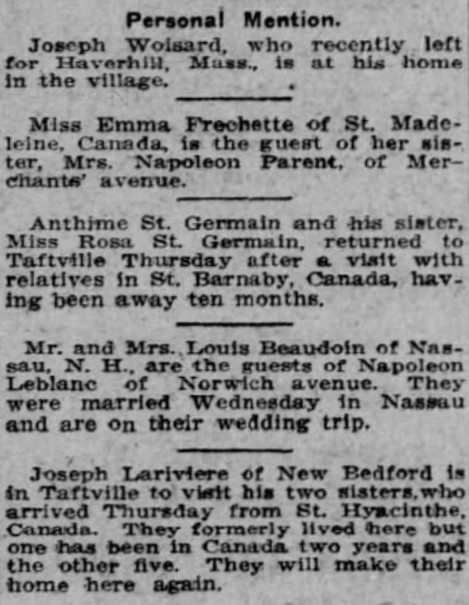

At first glimpse, we might imagine these back-page Americans to have been isolated and unmoored from their ancestral culture: they seem swamped by content relating to English-speaking Protestants; their names are sometimes misspelled or partially anglicized; and very often there is little to indicate that they are part of a minority ethnic group. Yet, as we undertake meticulous research in these qualitative sources, we quickly find local newspapers to be positively crowded with French Canadians. We cannot dismiss these immigrants and their American descendants as insignificant in the larger arc of Franco-American history, especially as they often constituted a higher proportion of the local population than they did in, say, Fall River. What’s more, the small slices of the French-Canadian presence in the U.S. Northeast are often a valuable complement to census and vital records. They provide a glimpse of community life, social networks, etc., in places that sometimes lacked distinct ethnic institutions.

The following excerpts offer an infinitely small portrayal of these back-page Americans—a small sample that cannot possibly do justice to their actual presence in the printed press. I have mostly set aside the sensationalistic front-page articles involving French Canadians. The press was very interested in accidents, assaults, suicides, and legal wrangling which, from the late nineteenth century on, did become major headlines. Occasionally, in such cases, people of French-Canadian descent received passing mention, as, for instance, Dr. Jean Baptiste Chagnon of Fall River, whose back fence abutted the infamous Borden property in 1892.

If It Bleeds…

We easily sense when newspaper reports found French Canadians to be exceptional, that is, when their background was worth noting, for often it was. Such was the case in 1841 when the steamboat Erie caught fire on the eponymous lake and sank after leaving Buffalo. Among the hundreds of victims was “Olivier Nadeau, of Montreal, a Canadian Frenchman, bound to Dubuque [Iowa], where he has a brother; aged about 19.”

Ethnic identification became less obvious as “Canadian” came to encompass English speakers. In December 1865, many workers were injured in a railway accident in Scriba, New York. Cars derailed and overturned when nearby cattle panicked and overran the track; the workers sustained injuries while jumping from the train. We know them to be of French descent from their names—or do we? John King, George Welch, Oliver Baillargeon, Joseph Paquin, and Louis Kennell were all injured and identified as Canadians. Also listed, though without reference to their national origins, were Alexander Bovay of Oswego, Thomas Wedge of Syracuse, and Thomas Lesperance. Were John King and Thomas Wedge English Canadians? Or were they in fact Jean Baptiste Roy and Damase Aucoin? Baillargeon et al., at least, are the forgotten French Canadians whose story has yet to be told in full.

If we skip ahead another generation, we find another obscured figure who better represents the idea of a back-page American:

James H. Cross, of Sweetsburgh, P. Q., employed in the pipe wrench works at Essex Junction [Vermont], while on a visit to Mrs. C. R. Archambault, his sister, went out in a small row boat in company with Eddie Benard, his nephew, and landed in front of the shed on the breakwater [in Burlington]. When getting into the boat again Mr. Cross stepped on the edge of the craft, overturning it, precipitating both into the water. Neither of them could swim, and Mr. Cross sank almost immediately, but Eddie succeeded in getting a hold upon the breakwater until he was reached by Harry Archambault and Robert Start, of the Nautilus. The body of Mr. Cross was recovered about 6:30 P. M., an hour and a half after the accident. The remains were taken to Sweetsburgh, P. Q., for interment.

Even with a reference to the Province of Quebec, we might think Cross to be an Anglo-Saxon Protestant. The burial act at the Catholic parish of Sainte-Rose-de-Lima in Sweetsburg tells a fuller story about the 28-year-old James Lacroix—a French Canadian.

Local and Personal

French Canadians appeared in Maine newspapers from an early date. In 1836, a contractor proposed to provide 2,000 cords of wood and aimed to do so by hiring Canadian laborers. These were likely migrant workers momentarily settled in central Maine. Yet we also find plenty of references to the mixed Acadian and French-Canadian settlements along the Upper St. John River, sometimes with description of their daily or home life. In June 1863, for instance, the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier shared news, first reported in the Aroostook Pioneer, that “Mr. Francis Thibodeau of Gran[d] Isle, has sowed this spring 122 bushels of grain, and Mr. Joseph Nedeau of Fort Kent, 75 bushels. Others in that vicinity have sowed a large breadth of land.” Since this was the full extent of the story, we might wonder whether it ought truly to have counted as news. Regardless, papers made space for people on the margins—providing information that can now serve researchers.

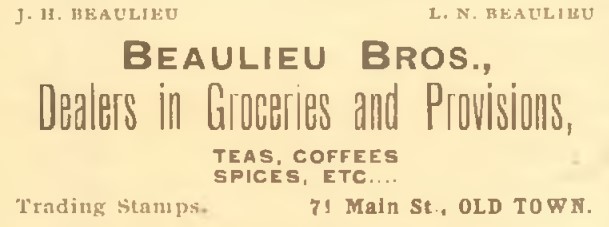

The back pages are in fact essential in humanizing our historical characters, as with one family from central Maine. In July 1893, Joseph Beaulieu, clerk of the Beaulieu Brothers store in Old Town, won an all-expenses-paid trip to the Chicago World’s Fair thanks to a contest organized by a store supplier, the Baker Extract Company. Off he went in September. By October, according to the local newspaper, more than thirty Old Town residents had visited the fair, a testament to the nationwide excitement surrounding the exhibition and to the growing accessibility of long-distance travel. Editors continued to make space for the moments of joy that are ironed out of other historical sources. In early 1911, the Old Town Enterprise stated that “Mr. Alexander Savoi[e,] a well-known employee of the Nekonegan Pulp [Mill] is one of the happiest men in Old Town. His sister whom he has not seen for 24 years is making him a visit. She lives in Meramichi, N. B.” We are thus reminded of the substantial research that has yet to be undertaken on nineteenth- and twentieth-century Acadian migrations to the United States.

Alas, too often French Canadians appear in these mainstream newspapers under obituaries and reports of illnesses. So it was when Edward Daignault, 76, passed away in February 1943. He had worked as a barber in Exeter, New Hampshire, for the better part of two decades and the Phillips Exeter student newspaper was quick to honor him. The article noted:

He was born in Quebec, Canada, but little else is known by local people of his career prior to the time that he set up his shop on Water Street opposite the present site of Merrill Hall . . . Always gruff but never grouchy, he would sometimes hold long arguments with his customers on politics or some other subject. He was always interested in a student and his career and would often share any snacks that he had on hand. It was characteristic of Eddie that he always gave as change for a dollar, a fifty cent piece, and never expected a tip.

Genealogical databases fill in the details: a slight man with blue eyes, Daignault had migrated to the United States in the early 1880s and married a Stéphanie Provost in Lowell. He cut hair in Bristol, New Hampshire, hardly a Franco-American hub, but seems to have always kept a home in Lowell, where he passed away. Like other snippets presented here, his is a story hardly heard in the annals of Franco-American history.[1]

The Melting Pot

The back pages, where, again, French Canadians are not identified as such, are also essential in tracing community involvement outside of strictly ethnic organizations, e.g. the parish groups and the sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste that we know so well. We often find French names listed indistinguishably alongside English ones—reminding us that ethnicity is not always the main story.

It is typically in the crowded back pages, not in big articles on national societies, that we find evidence of engagement in a larger community. In 1858, the Whig and Courier reported, “We have just been informed that Francis Thibodeau, Esq. of Madawaska, will contest Paul Cyr’s right to a seat from the Northern Representative district in this County, in the next Legislature.” No further details were offered. A more substantial piece on French-heritage people’s engagement with the Great Republic came five years later while the nation was sunk in civil war. A day after reporting on agricultural progress in Grand Isle and Fort Kent, the Whig and Courier highlighted the service to the country of a young man of Acadian descent:

Captain Joseph Thibodeau of Fort Kent, went out to Port Royal [South Carolina] a private in Captain Twitchell’s company, 8th Maine, from Patten. Afterwards he was promoted to Sergeant Major of the regiment. He was then appointed a 2d Lieutenant in the 1st South Carolina (colored) regiment of Volunteers, and has since been promoted to Captain. Recently he has returned home to Fort Kent on a thirty days’ furlough, and whilst at home was married to Miss Minnie Maloney of Fort Kent. He speaks of his company as bein[g] excellent soldiers, numbering 90 men, 60 of whom are as white as any men.—More than half the company can read and write and he regards them as brave and reliable as the bravest.[2]

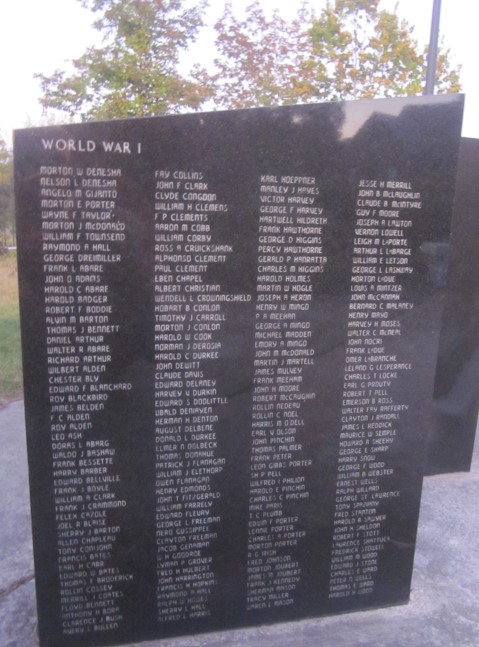

Military service and politics were areas in which French speakers could be valued as full-fledged members of the American experiment. In some fields of migration, their numbers were such that their involvement was seen as unremarkable. So it was in Clinton County, New York. During the presidential campaign of 1884, voters in Redford, west of Plattsburgh, organized a GOP club in support of James G. Blaine’s candidacy. Peter Tremblay and L. S. LaTulip became club officers. A quarter of members had French-Canadian names, among which: Bombard, Collette, Lafountain, Laport, Laramie, Picard, Robare, and Venne.

Americanization, we know, also occurred through “mixed marriages,” that is, marriages involving an Anglo-Saxon or Irish spouse. That reality is made plain in the following story from Lyndonville, Vermont—but perhaps that is beside the point, especially in small communities where French and English mingled freely and found joy in one another’s company.

About 35 of the friends of Miss Beatrice Ouillette gave her a very pleasant shower at the home of her sister, Mrs. Albert Croteau, last Thursday evening. The event was a complete surprise, and the young lady was delighted with the gathering, and with the many gifts, both beautiful and useful, which her friends brought in honor of her approaching wedding. Cut glass, silver and household linen, beside many articles in Pyrex and others useful for the household were presented. Ice cream and cake were served, and a pleasant social evening was spent. Miss Ouillette was married in St. Elizabeth’s church [in Lyndonville] at an early hour Monday morning, to Harold Blake, an ex-service man and now a railroad employee.[3]

The state marriage record shows that Miss Ouellette’s parents were both Quebec-born, with her father originating in Saint-Roch-des-Aulnaies, not a surprise for someone bearing that surname. The next day, the Caledonian-Record published a death notice for Jane Lemerise née Drouin. Lemerise was a native of St. Johnsbury who had lived in Lowell and Montreal. The list of attendees at the funeral highlights the diasporic nature of extended French-Canadian families who migrated in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. People who paid their respects came from Manchester, Lebanon, and Concord, New Hampshire; Lowell; Warwick and Princeville, Quebec; New York City; and Waterbury, Connecticut. Though not a person in the notice was identified as French-Canadian, everyone bore a French surname.

At last, another “marginal” area beckons our attention. Although we would hardly know it from existing research, Connecticut was home to a large Franco-American population in the early twentieth century. There, as elsewhere, Francos worked, attended church, and took part in community activities. Sometimes that community made the headlines due to controversy. So it was in Putnam’s Patriot in December 1930, when the paper reported on a lawsuit opposing the local Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste and George Potvin, its longtime secretary, who had become “a law unto himself.” But, tucked away in the same issue of the Patriot, we also find evidence that Franco-Americans were quietly entering shared social spaces through sports, veterans’ organizations, and Church groups. The local Knights were then preparing a play (“The Meanest Man in the World”) to be shown in January at the Bradley Playhouse, which still serves the community today. The cast included a nearly equal mix of English and French names, the latter including Joseph Bove, Grace Vegiard, Irene Bernier, Emil Marquis, and Lionel Charron. Franco-Americans were finding their way into a larger world.

The larger point, to put it succinctly, is that there is more to the Franco-American story than degrading industrial work and religious piety. However important those two aspects of daily life were to many families, we risk missing the richer texture of daily life, especially in less explored areas, if we do not fully utilize available sources.

Sources

- “Contract Wanted,” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, October 5, 1836, 3.

- “Most Appalling Calamity!” Burlington Free Press, August 20, 1841, 2.

- “Local and Maine News – Contested Seat,” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, December 24, 1858, 2.

- “Local and Other Items – Putting in the Seed,” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, June 12, 1863, 2.

- “Local and Other Items,” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, June 13, 1863, 2.

- “Distressing Accident on the Oswego & Rome Railroad,” Mexico Independent, December 14, 1865, 3[?].

- “The Campaign,” Plattsburgh Sentinel, September 26, 1884, 1.

- “Burlington Brevities,” Argus and Patriot [Montpelier, Vt.], July 2, 1890, 2.

- “The Home News,” Old Town Enterprise, July 15, 1893, 4.

- “Personal Items,” Old Town Enterprise, September 9, 1893, 5.

- “Small Talk,” Old Town Enterprise, October 7, 1893, 4.

- “Local News,” Old Town Enterprise, January 7, 1911, 4.

- “Lyndonville,” The Caledonian-Record [St. Johnsbury, Vt.], June 28, 1920, 3.

- “Mrs. Jane (Drouin) Lemerise,” The Caledonian-Record, June 29, 1920, 3:

- “Potvin Loses Suit Against Society St. John Baptist” and “Old Favorites in K. of C. Offering,” Putnam Patriot, December 24, 1930, 1, 2, 4.

- “Eddie, P. E. A. Barber for Nineteen Years, Dies at His Home in Lowell; Greatly Missed by Friends,” The Exonian [Exeter, N.H.], February 27, 1943, 4.

[1] Daignault was far from the first French Canadian to venture into Exeter. Some eighty years earlier, Pie Narcisse Legendre had made his mark as a teacher and a soldier, earning a mention in the local paper for his service in the Mexican-American War.

[2] Through this interesting instance of interracial collaboration, we should recall that French-heritage peoples as a whole claimed the privilege of whiteness (with its implied social hierarchy) just as much as their Anglo-Saxon neighbors.

[3] The last sentence was evidently added to an earlier submission. The wedding occurred on the day this issue appeared in print.

Leave a Reply