The French language has two expressions about those who come from afar or leave their home country. The first is “Nul n’est prophète en son pays”: one is not a prophet in his or her own land. The implication is either that one’s society will refuse to hear cold hard truths or that modern-day prophets are exposed as charlatans in their own society. The other expression is “A beau mentir qui vient de loin”: for all we know, the stranger or foreigner may well be lying. Their word should be approached with skepticism or suspicion.

Both expressions reflect a certain provincialism—a reluctance to trust the foreigner, the visitor, the migrant, or yet an instinctive rejection of new ideas and new people who might cause society to change. Of course, if these sayings are French, the attitude that they communicate is common to most societies. Very often there is little difference between this suspicious attitude and nativism or xenophobia.

We live in a world where accents can be intriguing, charming, exotic, seductive. Do I detect a French accent? Ooh la la. Accents instantly conjure visions of foreign lands and, under the best circumstances, they can spark healthy interest and provide an opportunity for intercultural understanding.

But in any society marked by nativism, an accent can instantly trigger underlying suspicion. The person “qui vient de loin” is thus reminded of their culture and their place, all because of their native language. Their accent comes to define them until they pass on. That person will forever say, without speaking the words, je viens d’ailleurs.

Accents become a convenient way for the majority in the host society to order and classify, to determine a person’s place and where they belong, geographically but also socially. Accents entail relations of power and that power is deeply felt when you are the one with the accent.

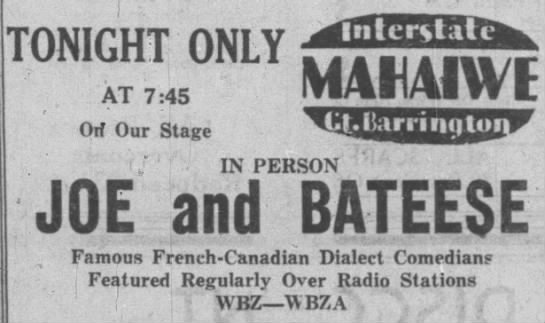

That, of course, was true of French Canadians who settled in the United States beginning in the nineteenth century. By the 1920s, the French accent had passed from the realm of social classification to that of entertainment. Without ever really intending to, I have collected dozens of reports of “dialect speech” in the Northeast. Typically, the local Rotary Club would welcome a distinguished Anglo-American storyteller to regale, in a false French accent, community members for an evening or two. At a time when Franco-Americans were rising economically and politically, dialect speech presentations may have helped to reassure status-conscious Yankees. Prosper Bender had had his revenge in the 1890s, when he reproduced the unique accent of rural Vermonters, but realistically few could reverse the power relations implied in dialect speech and expressed through ridicule.[1]

Everyone wants to speak other languages and yet, no one wants to speak with an accent—to mispronounce or make grammatical errors, to be corrected and risk being ridiculed, to expose themselves to judgment or classification, to instantly “out” themselves as foreign. The desire to feel included runs deep.

An accent does have its virtues. In a new host society, it communicates authenticity. Alas, if native-born Americans were quick to classify and marginalize people with foreign accents, Franco-American elites were, for a long time, also exclusionary. Francos who spoke with an English accent were, in fact, false Francos—assimilated individuals who had betrayed their ancestral culture in the interest of material advancement.[2]

Yet more, some francophones—setting metropolitan French as the gold standard—demeaned the language spoken by Franco-Americans.

Henry David Thoreau wrote that nineteenth-century Quebec “appeared to be suffering between two fires,—the soldiery and the priesthood.” In the United States, French Canadians were caught between the twin fires of French and English, the fires of Franco and American elites. As far as language was concerned, it was a case of “heads I win, tails you lose.” We should not be surprised that the children of French-Canadian immigrants were reluctant (or simply unwilling) to pass the language to the next generation.

Granted, this experience has not been unique to people of French-Canadian descent in the United States. Immigrants to Quebec have faced similar circumstances; so have the various groups coming to the U.S.

The challenge of navigating cultures old and new was common enough that historian Marcus Lee Hansen developed a theory best captured by his talk on the subject, “The Problem of the Third Generation Immigrant.” Hansen explained that

The sons and the daughters of the immigrants were really in a most uncomfortable position. They were subjected to the criticism and taunts of the native[-born] Americans and to the criticism and taunts of their elders as well. All who exercised any authority over them found fault with the response.

That generation sought to acculturate. As a way of providing for the generation that would follow, as a way resolving a tense cultural dualism, it sought to drop excess baggage and conform with the “mainstream.” But people belonging to the third generation, according to Hansen, looked forlornly upon that lost baggage—and it could do so because “[t]heir speech [was] the same as that of those with whom they associate[d].” They could only look fondly upon the past because they had achieved a more comfortable cultural position in American society. The grass is always greener on the other side, and in the past they imagined greener pastures.

* * *

The desire to renew with one’s roots—to unlock identity, to unlock heritage—through language persist among some third- and fourth-generations Americans. That is certainly present in Ben Levine’s documentary film Réveil: Waking Up French…! and in Susan Poulin’s recent TED talk. Others who did not grow up with the language are seeking to learn it.

Some of these individuals are facing the blockage that their grandparents or great-grandparents faced: the problem of the accent. They have to overcome the instinct to remain silent. They have to face the moment of self-disclosure—the moment when the accent slips out and they expose themselves to the judgment of the interlocutor—the moment when they “out” themselves as a stranger.

This may help to explain why unilingual, English-speaking Franco-Americans seem to have shed the impulse (formerly promoted by that narrow elite) to assail their own ancestors for language loss. The feeling is regret rather than resentment. There has also been increasing acceptance that “unilingual, English-speaking Franco-Americans” is not a contradiction in terms, that language is in fact not everything, as some Quebeckers would have us believe.

If history serves any purpose, above all else, it should teach empathy; the present moment in Franco-American history should invite appreciation of the linguistic struggles that different generations have faced on U.S. soil.

An accent as one of the engines of transformation in the history of Franco-American? Worth considering.

[1] That is still a sensitive issue, even when the “false French” is practiced by a Franco-American. In Maine, radio host Ernie Gagne sparked controversy with his character “Frenchie”; though he was primarily criticized for telling “dumb Frenchman” jokes, the way in which he used a French accent was also a matter of controversy.

[2] Writing in Le Forum in October 1998, Grégoire Chabot described the domineering approach of Franco-American elites in regard to language—the “Languestapo.” As late as the 1980s—maybe beyond—some middle-class Francos who led cultural organizations were quick to denounce and exclude their compatriots who spoke English. Language could help to sort “true French patriots” from the chaff. This spirit continues to thrive in Quebec.

Leave a Reply