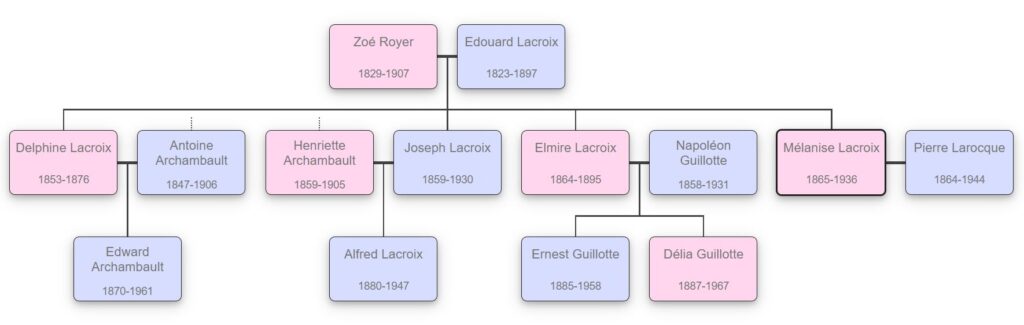

The funeral of Mrs. Melanise Larocque, 26 Broadway, was held from the home this morning [February 3, 1936] followed by solemn requiem high mass in St. George’s church. Rev. George Gagnon was celebrant, Rev. Elzear Larochelle deacon, and Rev. Albert Paquette sub-deacon. A delegation from the St. Anne Sodality of the church attended. Bearers were Edward E. Archambault, Alfred A. Lacroix, Ernest P. Guillotte, Abbee A. Duval, Arthur E. Larocque, and John B. Larocque. Rev. Father Paquette conducted the service in St. Patrick’s cemetery.

On the surface, this excerpt of the Holyoke Daily Transcript and Telegram would invite little more than a passing glance. Mélanise Larocque, who had lately reached her threescore and ten, had lived a fairly typical Franco-American life in Chicopee, an industrial city located across the Connecticut River from Holyoke, Massachusetts.

However, the names of the men who bore the body to its final resting place contain a history of chain migration and a lesson in transnational kinship. That story begins in southern Quebec in the 1880s.

A Carpenter in the City

Rosalie Archambault and her husband Olivier Goyette were middle-aged when they made the decision to start anew in the United States. Both belonged to the old French-Canadian families of the Eastern Townships. The Archambaults had settled in Dunham, near the international border, in the 1830s and, so far as we can tell, the Goyettes had followed closely. Both spouses had grown up in a bilingual and bicultural environment.

Over the course of several decades, Rosalie and Olivier seemed to live an itinerant life. Farming took them from Dunham to Sutton and to West Shefford. In this last place, in 1879, Olivier appears as a cultivateur, a term typically reserved for landowning farmers. The family nevertheless continued to seek better straits. In 1882 or 1883, the Goyettes, children included, boarded a train and rode down to Holyoke.

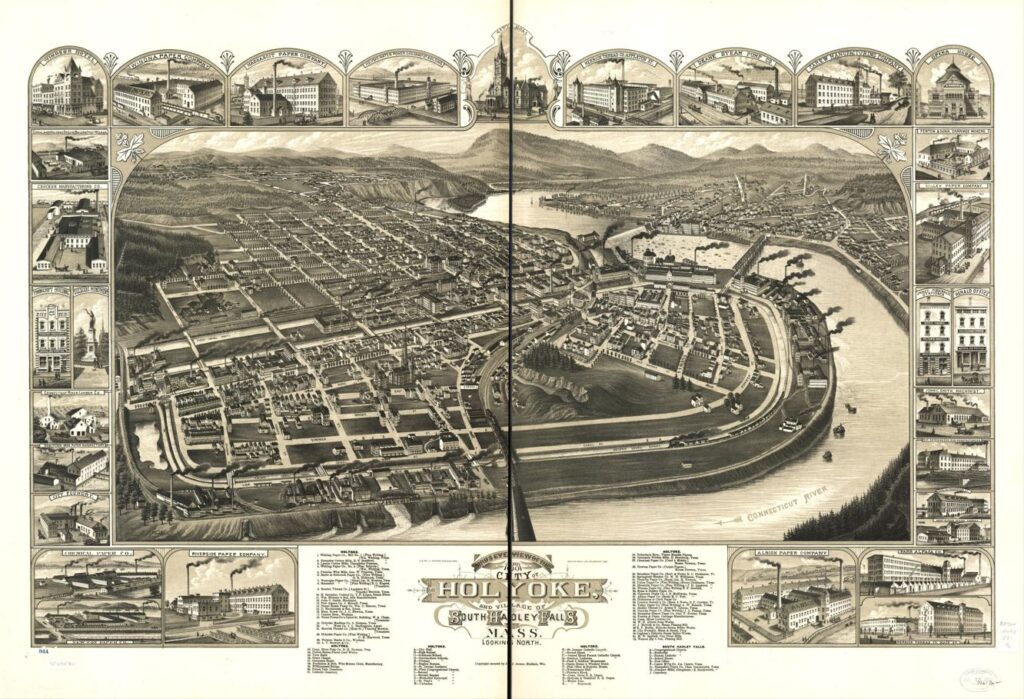

Many French-Canadian families in the Eastern Townships had crossed the border again and again, typically offering their labor just over the line in Vermont. The Goyettes knew many such persons. Holyoke, by contrast, entailed a lengthy journey and a change of lifestyle entirely. The recruitment activities of industrial concerns are part of the story. Holyoke had emerged as a large manufacturing center. Though the city was already attracting French Canadians, advertising north of the border had led to the arrival of perhaps as many as a thousand migrants from Quebec in 1879 alone. By the early 1880s, this surge had softened, but word had circulated. What’s more, the rapidly rising population had created a need for housing—and a need for builders. Olivier Goyette found work as a carpenter. At least one child would work as a mill operative.

Holyoke

Hampden County, where Holyoke and Chicopee are located, receives little attention in histories of Franco-Americans. At the turn of the century, it ranked fifth among Massachusetts counties for natives of French Canada. But more than one-third of Hampden’s foreign-born population hailed from French Canada and these migrants were nearly tied with the largest foreign group, the Irish. The numbers for Holyoke, in 1900, largely mirrored those of the county, though here the French Canadians outnumbered the Irish. At the time, Holyoke’s total city-wide population amounted to 45,712 and more than 11,000—be they native- or foreign-born—had two parents born in French Canada. In essence, a quarter of the city’s population was French-Canadian.

Not yet 60, Rosalie passed away in 1900 from cardiac dilatation, which caused fluid to collect in her lungs. Olivier died of stomach cancer at the Holyoke House of Providence, a Catholic hospital, five years later. Despite deaths that we would today consider premature, the Goyettes had the opportunity to witness an important transition in Holyoke’s ethnic history. Immigration from Quebec slowed, but the Franco-American community sustained itself through natural increase. As in other locales across the U.S. Northeast, textile manufacturing was a key ingredient in Holyoke’s growth and its emergence as an immigrant city. Lyman Mills had the largest labor force of any local corporation. By the 1880s, Holyoke had also gained prominence as a world leader in papermaking. That industry would face a steep decline in the wake of the depression of the 1890s.

Demographic stability paid dividends for the Franco-American population. Already, Holyoke textile mills offered higher wages than those of other New England cities. Peter Haebler, who wrote the most significant study of the local French community, has shown the growing number of men engaged in commercial activity at the dawn of the twentieth century: bakers, barbers, furniture dealers, saloon owners, etc. French-owned businesses were as much a part of the Franco-American institutional system as churches, schools, newspapers, and mutual benefit societies—though Holyoke boasted all of those, too. Precious Blood, the first national parish, was followed by two more, founded in 1890 and 1905 respectively. The community benefited from parochial schools, a French-language paper, La Justice, and a chapter of the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste. All the while, the immigrants experienced the stirrings of political activity and unionization.

In this universe, the Goyettes likely fared well enough. There were reports of contractors visiting the Holyoke railway station specifically to hire carpenters who were riding down from Canada. In fact, French Canadians quickly represented a disproportionate share of the city’s carpenters. Olivier’s skills would have found demand and, with the children’s wages, the family would have stayed afloat. Haebler states that “[i]n 1886, a year of economic recovery, carpenters earned $2-2.25 per day, two and one half times the average daily wage of a cotton mill operative” (74). In the late 1880s, French-Canadian carpenters began to organize to further protect their wages. The Goyettes had found an ethnic community and Olivier, an occupational network. Soon enough kinship also helped cement their place in an otherwise foreign world.

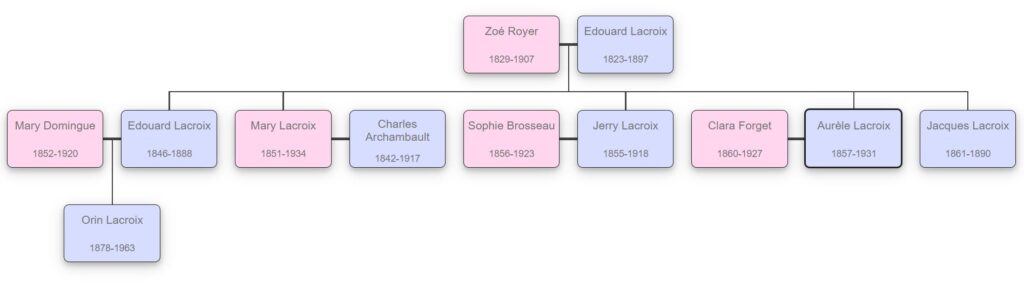

Edward Archambault

Enter Rosalie’s brother, Antoine Archambault. Antoine lost his wife in 1876. He had married Delphine Lacroix in Dunham, Quebec, seven years earlier, when she was only 16. Her death left three young boys without a mother. That such an early demise wasn’t unusual did not make it any less heart-wrenching for the family. The pang of loss may explain why Antoine waited six years to remarry. In the intervening time, the Archambault grandparents helped raise the boys in Dunham.

Antoine’s recurrent moves would indicate that he didn’t have much to pass on to his sons; the latter, having lost their biological mother at a young age, may have struggled to find peace with their stepmother, who soon had other children to care for. The circumstances linger in the haze of history, but we do know that the boys, having become young men, scattered.

The eldest, Edouard or Edward, perhaps the only one who could remember their mother, arrived in Holyoke in the fall of 1890. He was 20 years of age and this was his start in life. Holyoke was an eight-hour train ride away and may have seemed as good a destination as any. But the presence of kin likely weighed heavily in his decision. If the lives of other French-Canadian migrants are any indication, Olivier and Rosalie would have returned occasionally, perhaps yearly, to the home parish to nourish ties with family. We might imagine that, in July 1890, while mill workers evaded the unbearable heat of the factories and traveled north, Edward, pondering his options, sat with his uncle Olivier and asked about life in Holyoke.

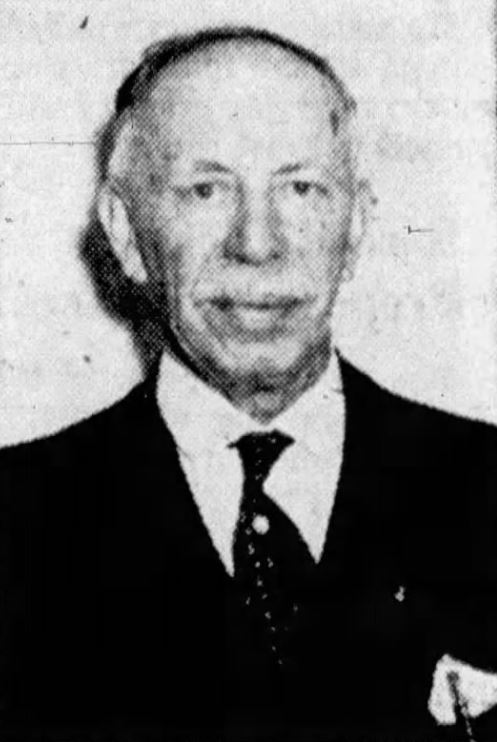

The young man lived up to his potential. For four or five years, Edward was a coachman for the Ramages, a well-to-do family with interests in the papermaking business. He worked in stables, then became a furniture salesman, and later owned and operated his own furniture business. He would sell his company and become a partner in Octo Furniture with two other French-Canadian immigrants, one from Les Cèdres, the other from Joliette. The diverse geographical origins of the three business partners hints at the making of a new French-heritage community, from disparate elements, in the United States. But, ultimately, this story concerns the community of kinship, of which Mélanise Larocque’s 1936 funeral is imperfect evidence.

The Cousins Come

In true French-Canadian form, Edward Archambault had a lot of cousins. Through him, in the 1890s and early 1900s, family members seeking to improve their circumstances learned about western Massachusetts.

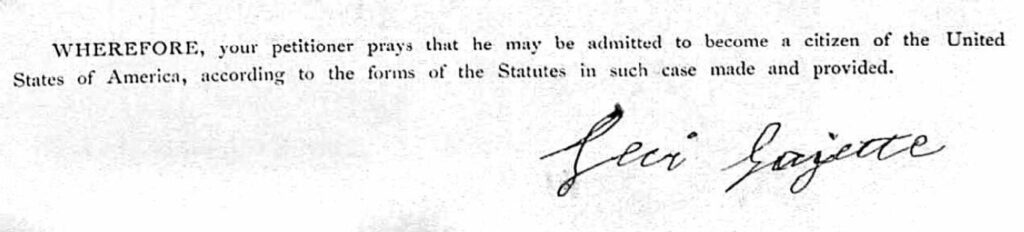

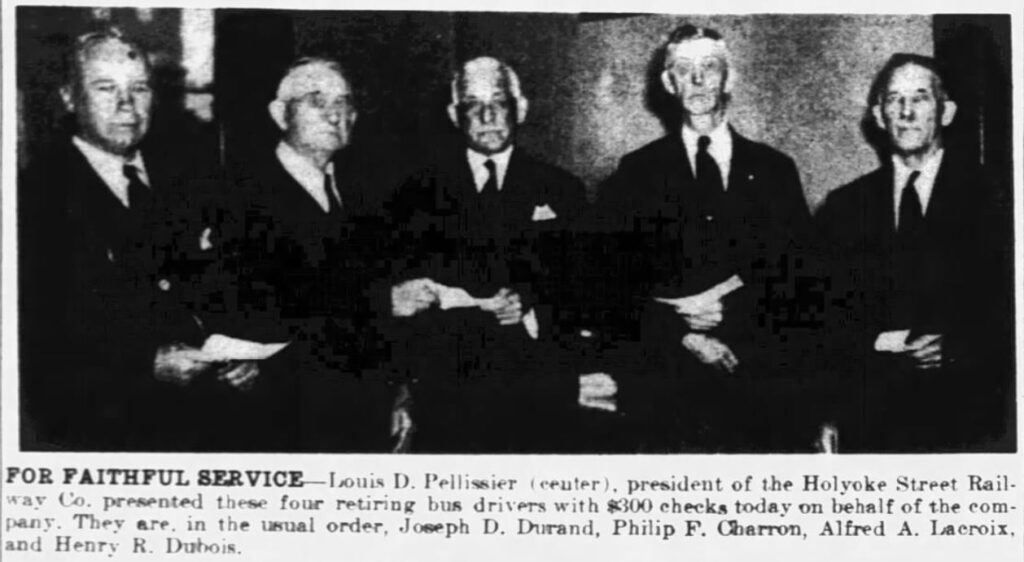

Alfred Lacroix migrated in 1898. He and Edward may have enjoyed a special bond as double cousins: Lacroix siblings had married Archambault siblings. Alfred also settled in Holyoke, where close relatives eased the transition to his new milieu. There he met his future wife, an Irish immigrant named Margaret Courtney. Beyond kin, he found a home in the reconstituted communities of Franco-America, his membership in the Massachusetts Catholic Order of Foresters being but one hint of new connections. Like Edward, Alfred found opportunities outside of the mills. He became a streetcar conductor and later a bus driver in Holyoke. By the time he retired in 1946, he had driven for the Holyoke Street Railway for forty years. The three drivers who retired at the same time were all French-Canadian. Each received a check for $300 for his years of service to the city.

Next came Delphine Délia Guillotte, born in 1887 and named in honor of her deceased aunt. She was a first cousin of Edward and Alfred. She moved to the United States at age 20 and likely stayed with relatives. Two years later, in 1909, she married Abbée Duval in Holyoke. The young couple moved to Amherst. The kinship network may have paid healthy dividends. Duval became a “motor man” for the Holyoke Street Railway in 1910. It seems likely that Alfred had put in a good word for him. From 1932 to his retirement, Duval was an employee of Amherst College—several worlds removed from the rural parish of his birth.[1]

In the fall of 1910, Délia’s brother, Ernest Guillotte joined the fray. According to travel documents, Ernest and his wife Ida were headed to Holyoke to join Ida’s parents. Ernest worked as a butcher.[2]

Matante Mélanise

In the intervening time, another family crossed the border and journeyed to the Holyoke area. Minus a set of twins who died a few months into life, Mélanise Lacroix was the last of the children of Edouard Lacroix and Zoé Royer. Born in 1865, she was five years of age when her eldest nephew, Edward Archambault, came into the world; she was 10 when her sister Delphine died. Like her siblings, she grew up at Gilman’s Corner in Brome Township. She married Pierre Alphonse Larocque, who alternately worked as a barber, as a tinsmith, and as a farm worker, and they had four children. Three were born in the Province of Quebec; the lone girl, Blanche, was born in Vermont in 1892. The Larocques thus knew something of the Great Republic—and Pierre Alphonse’s varied occupations indicate instability that might entail a search for new opportunities. In 1909, they took the decisive step. The next year, a census enumerator found them in Chicopee, where Pierre Alphonse was working in a gun factory. A decade later, he was cutting hair again.

Thus it was that four distinct branches of the extended Lacroix family, in addition to Rosalie and Olivier Goyette, had made their way to Holyoke and surrounding towns by the 1910s. The oldest of the migrants—Mélanise and her husband—were ironically the last to cross. Their nephews and nieces, at the age of adventure, had established a beachhead.

It would be tempting, just as the last family unit settled in the Holyoke area, to spy an inevitable splintering of the kinship network, with those in Quebec and those in Massachusetts each going their own way. On a large scale, such is the story of the last century. However, family members keenly maintained relationships through rail travel, correspondence, telegrams, and, after the First World War, “motoring.” In the short term, affective bonds trumped the trajectory of an entire culture.

An Abridged Timeline of Encounters

Generations later, it is near-impossible to quantify or qualify these family relationships. Still, social notes in newspapers left a trail of crumbs that enable us to say something of cross-border connections. Relatives met and mingled—and not merely at weddings and funerals. For some time, neither distance nor the border posed a threat to the connection between Holyoke and the counties of southern Quebec. To wit:

1908: A brief note from Gilman’s Corner, West Brome, in the Sherbrooke Daily Record reads, “Messrs. F. and J. Lacroix have returned from Holyoke, Mass. They report hard times.” The first of these men is presumed to be Alfred, known to close family as Fred.

1910: Ernest and Ida Guillotte travel from Holyoke to visit Ernest’s father at Gilman’s Corner.

1914: In Chicopee, Mélanise and Alphonse’s daughter, Blanche Larocque, holds a Hallowe’en party to coincide with her cousin Rose Eva Guillotte’s visit from Quebec.

1922: The Guillottes of Knowlton, Quebec, host a reunion for the ages that captures the varied journeys of the Lacroix family. Mélanise, of Holyoke, reunites with her surviving sisters, Mary Ann Lacroix of Burlington, Vermont, and Angélique Lacroix of Gilman’s Corner.

1930: The Guillottes of Knowlton host another large family reunion with the Holyoke contingent—Edward Archambault, Alfred Lacroix, Délia Guillotte—in attendance.

1931: All of the Guillotte siblings attend the funeral of their father, Napoléon, who passed away at the age of 72, in Sweetsburg. Later in the year, George Lacroix and several of his children visit his brother Alfred in Holyoke.

1937: Alfred travels north from Holyoke for a Lacroix reunion in Sweetsburg that also includes his surviving siblings—George, Frank, Adélard, James, and Marcel—and their cousin Edson.

1939: James Lacroix and his son, of East Farnham, Quebec, travel to Holyoke to visit relatives, including, we presume, James’s eldest brother, Alfred.

1952: Edward Archambault visits his cousin, Emma Guillotte, and her husband, J. A. Bourgeois, in Sherbrooke. The following year, the Duvals drive to Knowlton from Holyoke.

Cross-Border Connections

Without some historical detective work, we would remain oblivious, first, to the fact that four nephews, each with a different surname, served as pallbearers when the body of their matante Mélanise was laid to rest. Taking advantage of information relayed by kin, all four had immigrated successively between 1890 and 1910—all from Dunham, Gilman’s Corner, and Sweetsburg, and all to the greater Holyoke area. Then there were the last two bearers, Arthur and John Larocque, who motored from Quebec to attend the funeral, further evidence of enduring cross-border ties. The same migration story that had begun in 1882 or 1883 was still unfolding in 1936, as it was when the furniture dealer visited Sherbrooke in 1952. Arguably, it still was in 1972 with the passing of Mélanise’s son, George N. Larocque, of Chicopee Falls. George was the last survivor of the immigrant generation. Though family ties withered, long after, the next generation and relatives in Quebec remembered visits to and from family across the border.

Though it is fashionable in immigration history to write of “push” and “pull” forces, this macroscopic view easily misses the human element and the connective tissue that informed individual decisions, from physical infrastructure (steamboats, railways) to information networks (correspondence and newspapers) and finally kinship. Yet, the chapter that began with Rosalie and Olivier Goyette was likely mirrored tens of thousands of times in the great saga of Franco-American history. This should stand as an invitation to merge history and genealogy to better understand the significance of kinship networks.

Sources

More information on each of these individuals is available through their WikiTree profiles. In addition to Massachusetts newspapers, the Sherbrooke Daily Record was critical in tracing continued interaction across generations. For more on the history of the extended Lacroix family, see Part I and Part II of A French-Canadian Journey. Histories of return migrants are relatively few. For one such story, see Those Who Returned: One Family’s Journey to the U.S. and Back. The Guillaume Larocque in the latter story was a distant cousin of Pierre Alphonse Larocque. Peter Haebler’s dissertation is available online; so is data from the federal census of 1900.

Haebler’s work was preceded by Constance Green’s pioneering study of Holyoke, published in the 1930s. The wife of a textile company treasurer, Green carved out a career in research and teaching. She received a Ph.D. in 1937 and, years later, earned a Pulitzer Prize for her work on Washington, D.C.

[1] Abbée and Délia’s son David Duval, a first-generation American, served in the Second World War. He graduated from Boston University and became a teacher and later a school principal. He passed away in 2017. Although not all Franco-American families rose socioeconomically, the experiences of the Archambault, Lacroix, Duval, Guillotte, and Larocque lines hint at opportunities to close the gap—educationally and professionally—with “old-stock” Americans over the course of several generations.

[2] As we look at the occupations of the male migrants on U.S. soil, we see an ability to parlay skills from their rural background into gainful occupations. Olivier Goyette had learned at the very least basic carpentry. Edward Archambault knew how to work with and handle horses. Ernest Guillotte likely learned how to butcher animals on his father’s farm at Gilman’s Corner. Pierre Alphonse Larocque had cut hair in or around Cowansville. In other words, far from being helpless and disoriented when stepping onto the platform, in Holyoke, migrants could repurpose themselves in familiar ways.

Great stuff , Patrick. At an earlier time my Crosier and Kelley ancestors were just over the Mountains in Peru, Washington and Hinsdale Mass

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - April 12, 2025 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte