The latest issue of the academic journal Recherches sociographiques deserves the attention of anyone and everyone with an interest in the transnational history of Acadians and French Canadians. It honors the sixtieth anniversary of a pioneering issue on French-Canadian migrations with a new set of articles that highlight the extent to which, in the intervening decades, the frontiers of Franco-American history have widened. Engagement with le fait français aux Etats-Unis may not be what it once was in Quebec; nevertheless, researchers continue to challenge our understanding of the Franco-American past through archival research and new conceptual approaches.

This special issue features an updated overview of the field by veteran scholar of French-Canadian migrations Yves Frenette. The articles in the issue’s first section reflect the general trajectory of research seen in Déploiements canadiens-français et métis en Amérique du Nord (18e-20e siècle), published several years ago. Scholars have leaned on demographic databases to define the when, where, and how much of migration particularly at the height of the grande saignée. The next section is the most exciting for this researcher, as it includes important studies of Acadian migration flows between the Maritimes and New England. Such studies have been few and far between. The gendered dimension of these migrations adds to their significance. In the third section, we find explorations of oft-overlooked migration fields: Michigan, in a study that adds to Jean Lamarre’s work, and my own article on institutional development in Vermont and New York State. In addition, Pierre Lavoie and Sandria Bouliane are charting relatively new ground with a study of sound and music in the transnational French-Canadian world.

More direct and substantial engagement with all of these articles will, I hope, eventually come to this blog. Until then, it’s a case of “write what you know”: a much briefer overview of my contribution.

Titled “S’unir et survivre: genèse de l’organisation communautaire des Canadiens français aux États-Unis (1838-1861),” my article covers a period of French-Canadian migration and settlement that is still little studied. Works often acknowledge in passing that emigration from Quebec (then Lower Canada) began prior to the U.S. Civil War, but that is a far cry from in-depth research that shows the important elements of continuity from the 1840s to the 1870s. My article is also a French-language sequel to my recent piece in the American Review of Canadian Studies, “Prelude to the ‘Great Hemorrhage’: French Canadians in the United States, 1775-1840.”

Efforts to organize nascent Franco-American communities did not originate in the 1860s, I argue, nor in the large manufacturing cities that we often associate with the French-Canadian diaspora. Experts readily acknowledge that Burlington, Vermont, had an ethnic parish as early as 1850, but even this is to begin mid-story. Two exiled Patriotes, Ludger Duvernay and Robert Shore Milnes Bouchette, spearheaded efforts to build a Canadian church in Burlington in 1841 following the visit of a French bishop. In the 1840s and 1850s, French-Canadian congregations established churches in Troy, Plattsburgh, and Watertown, New York, among other places.

As it turns out, religion is only part of the story of community organization in the United States—and perhaps not even the most significant. The ideology of survivance was still evolving; at this time, it did not have the clerical character that would be a given from the 1870s onward. Politics, on the other hand, proved to be a defining aspect of collective French-Canadian action on U.S. soil.

This was true of the hundreds of Patriotes (Duvernay and Bouchette included) that found refuge south of the border following the failed uprisings of 1837 and 1838. The emigrants who, in their wake, followed economic opportunity were also politically engaged and active. Enthusiasm for the annexationist movement of 1849-1850 makes this plain. When the governor general of Canada signed into law the Rebellion Losses Bill, in 1849, disenchanted Montrealers—predominantly but not exclusively anglophone—sought a regime change: they began advocating the annexation of the Canadas by the United States. This movement had a second life among francophones in the United States. From their exile, they raised pointed questions about the political and economic state of the colonies, conditions that had forced them abroad. In January 1850, the Montreal-based L’Avenir published the names of more than 600 French-Canadian men then living in Cohoes, Lansingburgh, and Troy who had signed pro-annexation petitions.

Alongside national parishes, another pillar of survivance, specifically the network of fraternal and mutual benefit societies, is often traced back to 1850. Some historians have seen in New York City’s Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste, founded in the spring of 1850, the first such organization in the United States. But, as with Burlington, the story is more complicated. The founding meeting was preceded, minutes earlier, by an annexationist gathering. The group adjourned and instantly convened again for a separate purpose: the establishment of a non-partisan, apolitical “national society” whose aims would be cultural. We may wonder whether this society would have seen the light of day without the connections forged through political activism.

Two figures in particular exemplify the meeting of politics and cultural advocacy—two figures who anticipated the role that Ferdinand Gagnon would later play in the Franco-American world and who merit a place in our historical narrative. Joseph Napoléon Cadieux and Jacques Edmond Dorion, both physicians, led somewhat itinerant lives. They left Canada as young men and sought a clientele abroad. Both held strong views. On the Canadian political spectrum, they were Rouges, liberals favorable to far-reaching democratic reforms and suspicious of clericalism. In New York State and Vermont, their aspirations and their sympathy for annexation blended with their desire to see expatriates united and dedicated to their culture. They aimed to establish French-language newspapers, cultural institutes with libraries and lectures, and fraternal organizations. Few of these ventures would survive, but they had a noble legacy in larger population centers farther east.

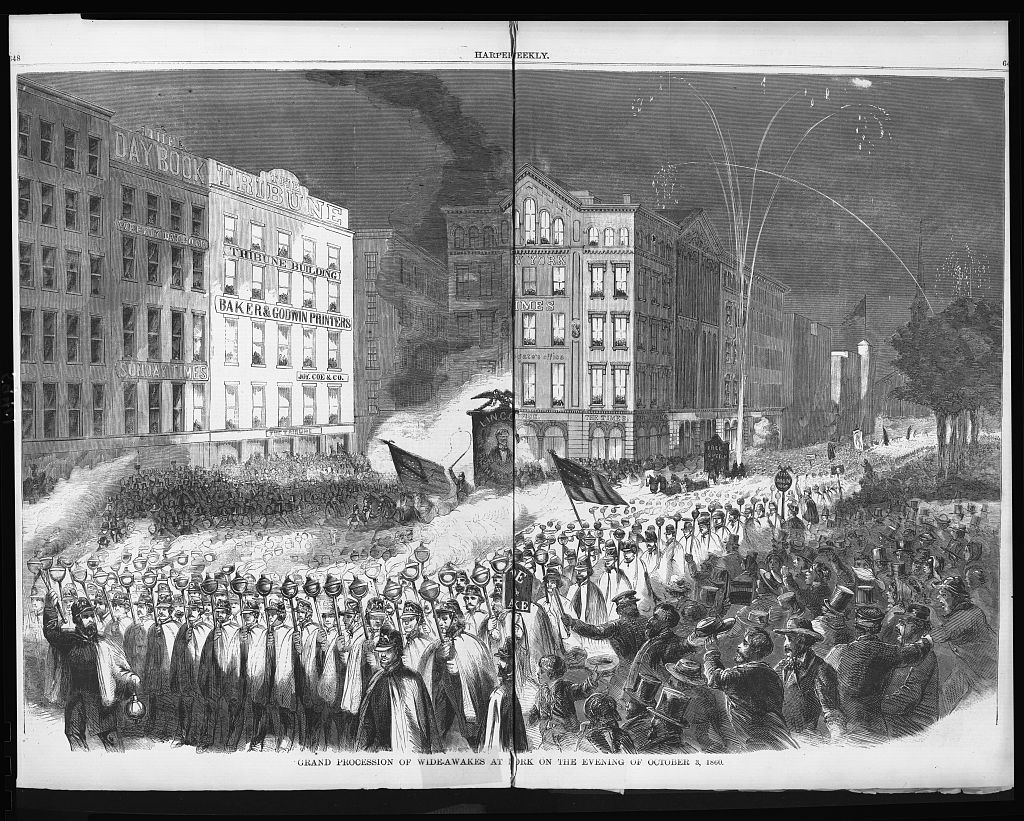

Lest we think these two figures were comrade-in-arms, their Canadian politics did not transfer across the border in the same way. Dorion was a Democrat. Perhaps he identified with the principles of small government and grassroots politics. Many Catholics had already found a home within the Democratic Party prior to the Civil War. What’s more, by 1860, the Republicans had absorbed elements of the xenophobic Know-Nothings. But Cadieux was a Republican and he could find equal justification for his position. He likely saw slavery as a moral issue and identified with the majority political opinion of the North—this may also have been an unconscious way of creating distance from other immigrant groups in the region. The two physicians almost certainly saw one another as rivals rather than allies. As things stand, there is no documentary evidence of collaboration between them. Partisanship trumped the cause nationale, though it is unclear whether more might have been achieved otherwise. Their cultural efforts were continually challenged by the limited means and relatively high mobility of migrant families.

The physicians also exemplified the two destinies of French-Canadian migrants. Dorion repatriated with his family in the first year of the Civil War. He accepted the editorship of the Courrier d’Ottawa. Cadieux stayed and attempted to raise a francophone regiment for service in the war. Long afterwards, he continued to preach annexation in the Northeast and Midwest, an increasingly marginal position. Although he also became a temperance advocate, in time he was persona non grata within the Franco-American establishment and in other circles. He was indicted for domestic violence and later, when other criminal charges were laid, a newspaper deemed him a “dead-beat.”

Having written a book about politicians, I am conscious that the Franco-American historical narrative is not starved for indistinguishable middle-class men, least of all self-aggrandizing figures with a penchant for casual violence. For one thing, though many cultural groups and institutions were shepherded by the middle class, the fate of the culture itself always lay with the great mass of people that enjoyed far less economic opportunity. This simple fact may explain why most readers will have never heard of Dorion and Cadieux. These leaders’ big, bold projects found limited support and ultimately foundered due to the realities of expatriated communities that were meant to anchor a transnational French Canada. We must also acknowledge the labor of women mentioned only in passing in contemporary newspapers, as when they prepared meals for large gatherings or organized church bazaars—or simply performed the toil that enabled their husbands and fathers to go into the world.

We should know about Dorion and Cadieux—but chiefly in the sense that we should know about the origins of this thing we call Franco-America. A rural Little Canada developed on the western shore of Lake Champlain in the 1780s and 1790s. Transportation and communication networks improved and economic exchange increased. The first report of emigration as a collective phenomenon appeared in 1826. Migration towards central Maine, the Champlain Valley, and the Great Lakes occurred thereafter. The exile of the Patriotes drove renewed attention to the United States. In the 1840s and 1850s, the grande saignée was undeniably under way. By understanding the world our two physicians inhabited, we stand to appreciate the migratory context they inherited and the experiments that would be taken up, more successfully, in eastern New England.

My article, then, is a challenge to scholars and to a wider reading public. The realities of early French-Canadian migrations, culture, and community organization occurred outside of the purview of Franco-American history as written in the last sixty years. We can now change that.

For more on French Canadians in the United States prior to the Civil War:

- The Franco-American Origin Story in Parish Records

- Early Canadian Migrations to the United States

- American Annexation of Canada: The Case in 1845

- Maska, Mexico, and Pre-Civil War Migrations

- Canada to California: Defying Distance in the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- A Canadian Excursion to New York City in 1851

- Review: Brettell, Following Father Chiniquy

- French New York

Leave a Reply