See Part I here.

It might be argued that Mallet’s life only really conforms to the “great man” theory of history and therefore actually says very little about Franco-Americans’ lived experience. Perhaps. And yet, to late nineteenth-century Francos, Mallet mattered a great deal.

His prominent role at the Rutland Franco-American convention, in 1886, made this plain. Delegates in Rutland had much to discuss. Fall River’s lengthy Flint Affair had recently concluded with mixed results. Franco elites were still pushing the cause of naturalization. Most significantly of all, the execution of Louis Riel in November 1885 had raised interethnic tensions to new heights in Canada.

To Franco-American leaders who had spent the prior five years fighting the rhetoric of the Wright report, the Riel controversy felt all too familiar. The matter was brought home by the time Riel had spent in New England and Mallet’s own relationship with Riel. The Metis leader may in fact have stayed with Mallet while travelling to Washington in 1874.

In the fall of 1885, Mallet, a mid-level civil servant, had communicated with President Cleveland, a Democrat, to see if anything could be done about Riel’s impending hanging, as Riel was a U.S. citizen. Cleveland ultimately agreed with Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard and—likely seeing this as a Canadian domestic matter that could only poison international relations—chose not to intervene.

Mallet no less obtained the office of “Indian Inspector” in 1888. A brief stint as an “Indian agent” at Puget Sound in Washington State, in 1876-1877, as well as his connection to Riel and long career in government may have aided him here. The Senate confirmed the appointment. Yet, only a few months into his position, Mallet found himself in the midst of controversy. New Hampshire senator Henry W. Blair, a Republican, alleged impropriety in Cleveland’s handling of the Riel issue. He asked the administration to turn over documents concerning the entire affair and alleged ethnic motives in Cleveland’s unwillingness to help an American citizen of French-Canadian descent. (Blair, just like French Canadians, was actively choosing to minimize the Indigenous part of Riel’s heritage and his distinct identity as Metis.)

Senator Blair seemed to suggest that the Cleveland Administration had silenced Mallet. Did Mallet become a liability? His dismissal in the fall of 1889 might at first glimpse suggest as much.

Mallet himself was told that other factors were at play—but partisan politics were still at the heart of the matter. Benjamin Harrison had defeated Cleveland in the fall of 1888. Some Republican leaders alleged that Mallet had left his post as Indian Inspector specifically to promote free trade in the Eastern states, an unwelcome gesture defying the high-tariff policies of the GOP. Secretary of the Interior John Noble confirmed that it was this allegation that had gotten Mallet fired.

At the Lay Catholic Congress held in Washington, D.C., Mallet shared this story with a delegate from Fall River and soon the story travelled throughout the Franco press, to great outrage. (This came amid the actual controversy surrounding the Lay Congress and the denunciation of ethnic societies.)

According to l’Indépendant, a Republican newspaper based in Fall River, Democratic papers (we might think of Le Messager, in Lewiston) made matters much worse for Mallet by claiming him as their own. Secretary Noble apparently offered Mallet something of a temporary consolation prize until he could be returned to Indian Affairs, but the Democratic press was said to be imperiling Mallet’s place in government. As l’Indépendant charged, shouldn’t those papers instead devote their energies to the protection of French denominational organizations?

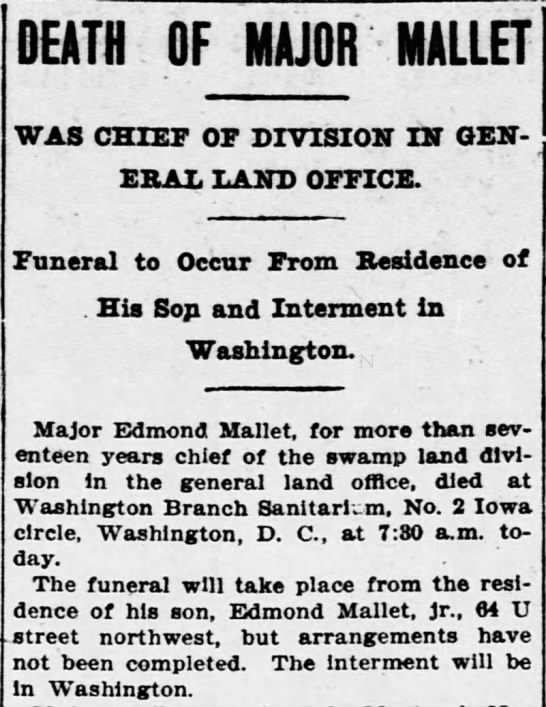

In the end, there was little sign that Mallet’s actual performance in office—or his willingness to serve the American government’s repressive approach to Indigenous peoples—had anything to do with the loss of the inspectorship. A consolation prize did come, as his obituary later revealed: “in January, 1890, after being out of office a few months, [he] was made chief of the swamp land division in the general land office, and there he remained until stricken with fatal illness.”[1] Of course, as he found out, there was no draining the Washington swamp. He passed away in 1907, aged only sixty-five.

What do Mallet’s life and career tell us? As the opening suggests, though he himself reached out to Franco-Americans, he was also made by them. In the 1880s, they quickly seized on Mallet, his heroic war service, and his place in government to cover themselves in the prestige they desperately needed. This, again, was during the time of the Wright affair, the Frank Foster affair, the Flint Affair, the Lay Congress affair, the Cahensly affair… the list goes on.

But there is yet greater significance to be found in this saga. First, Louis Riel’s execution became a cause célèbre on both sides of the border; it helped to cement among French Canadians a sense of ethnic siege that also transcended boundaries and governments. It fueled fears of an encroaching pansaxonisme. Second, by the end of the 1880s, Franco-American elites, exchanging with one another through the French-language press, were already highly politicized. Their newspapers were stridently partisan. Behind the grand eulogies later dedicated to men like Gagnon and Mallet, seen to be noble representatives of the French-Canadian “race,” lay highly controversial encounters that split Francos against themselves.

More on Franco-American politics in a future post.

Sources

Lauren L. Basson offers a fascinating glimpse of the Riel affair’s place in U.S. politics in White Enough to Be American? Race Mixing, Indigenous People, and the Boundaries of State and Nation (2012). Thomas Flanagan discusses Riel’s ties to Mallet in Louis ‘David’ Riel: Prophet of the New World (1996). Contemporary newspaper excerpts complemented the research for this article.

~ ~ ~

[1] Mallet was adamant about taking a position that would not compel him to travel to Western states.

Leave a Reply