Lucina Young. Olive Ash. Leafy Brown. Lydia Chase Cook. Mattie Spaulding. Harriet Titus Gaudette. Eliza McMahon. Caroline Bettis.

Undoubtedly, some of them wished to be forgotten, their lives and tragic deaths forever passing from human memory. The history I offer here may therefore be, in Voltaire’s words, “a pack of tricks that we play upon the dead”—cruel tricks. But there may also be, in this effort, an act of sympathy and understanding that was never extended to these eight women while they lived their final days.

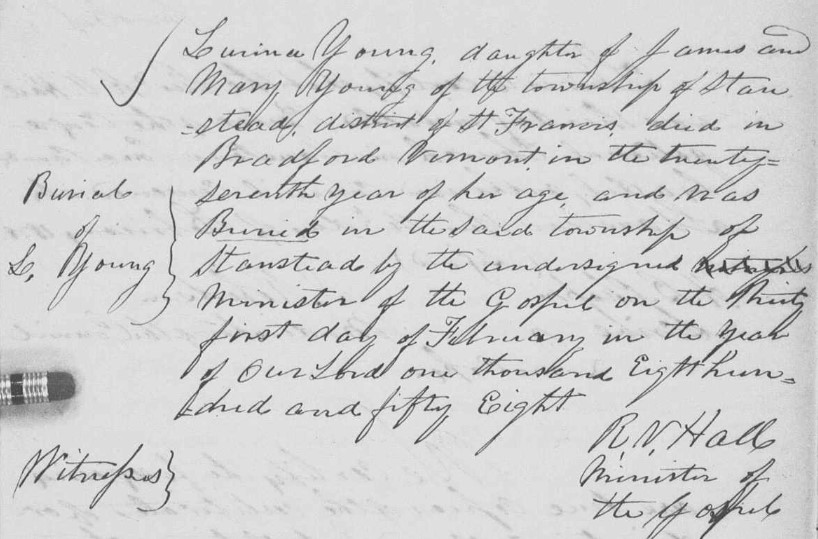

Lucina Young died in Bradford, Vermont, 70 miles as the crow flies from her home in Stanstead, Lower Canada, in 1858. The Congregational Church record marking Young’s funeral holds many silences. In fact, we would not know why she went to Bradford or why she died at such a young age (twenty-seven) were it not for the woman who died under the same circumstances, poor Olive Ash, two days later, also in Bradford.

These two women likely never met, but there was much to connect them. Both were single. Both were pregnant. Both faced a heart-rending decision. Would they seek to end the pregnancy or face shame, dishonor, and isolation?

Both chose the former—and both died from the procedure.

Young’s death only became suspicious because Ash’s cousins alerted local officials when the latter died. A Vermonter, Ash had undertaken a fifty-mile journey to see Dr. William Howard. The suspicions of her cousins led to the disinterment of her body after her death at Howard’s practice. The examiners noted unmistakable signs of an abortion or attempted abortion. It now seemed certain that Young had sought the same procedure.

The distance these women covered matters in several respects. It suggests broad knowledge networks. Women knew or could learn about physicians (often so-called) willing to perform such risky procedures even in far-away places. In these cases, distance also signified desperation—a desperate desire to escape a lifelong stigma. Publicly, pregnancy outside of marriage could not be admitted to, but, just as women might pass along rumors of a doctor who could “make the problem go away,” so entire communities might whisper about this or that girl.

The Leafy Brown case exemplifies the very thin line between what could and could not be spoken. Brown died in northern Vermont ten months after Young and Ash. Her body was disinterred and the examination resulted in the same conclusion. As one newspaper reported, during an inquest, “the mouths of both father and mother were hermetically sealed against revealing anything that would tend to throw light upon the authors of this great crime. The mother testified under oath that she did not know what ailed her daughter, and that she never asked.”

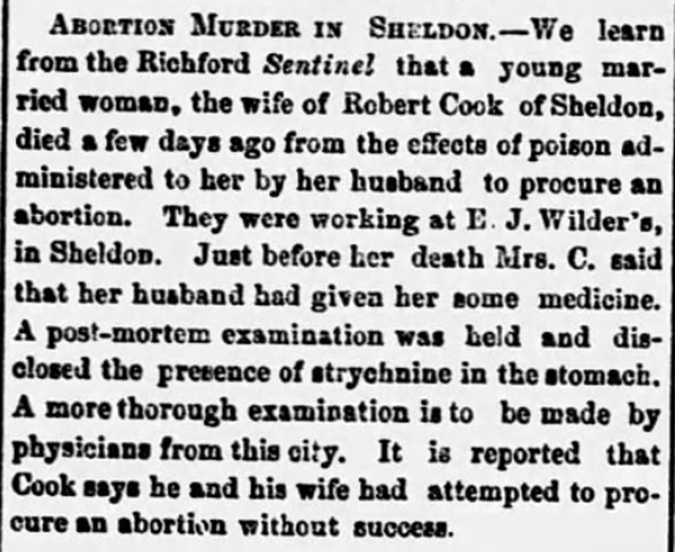

The circumstances of each of these tragic deaths matched almost exactly those of Mattie Spaulding, a Vermont girl who died in New York, just over the state line, in 1874. But not all abortion cases were alike. In 1872, Lydia Cook of Sheldon drank an abortifacient administered to her by her husband Robert. She died suddenly. An examination found strychnine in her stomach. During the subsequent investigation, Robert Cook stated that he and his wife had resorted to this method after failing to find someone to perform a surgical abortion.

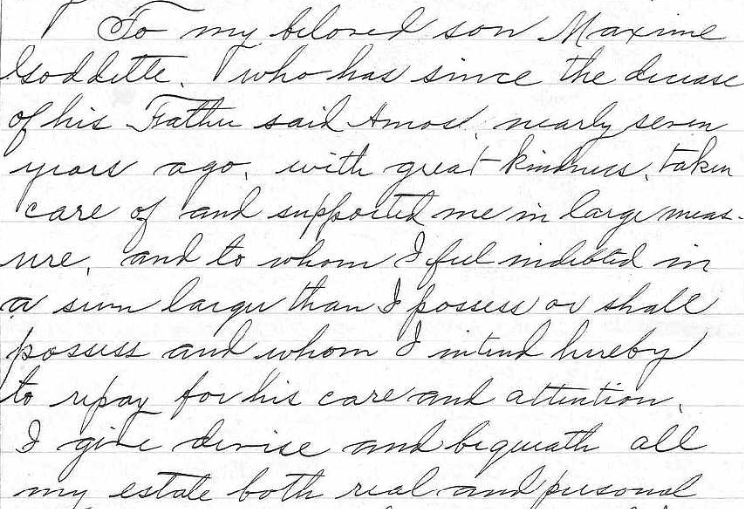

Five years later, the story of another married couple broke into the press. Maxime Gaudette, a French Canadian who had grown up in Vermont, married Harriet Titus around 1873. They lived briefly in New York State and then Maxime was hired as a wage laborer on a Winooski farm. We do not know whether, at any point, the marriage seemed like a match made in heaven. By the fall of 1877, the relationship had broken down.

In November, it happened: Harriet left Maxime and joined her mother in Rutland. It is unclear whether she was seeking a new home or leaving momentarily to seek an abortion. An abortion there was—and then followed six days of physical agony, during which time she confessed her act to a friend. The situation was so dire that an unsigned letter reached Maxime, beckoning him to his wife’s bedside. He came. Physicians were helpless and Harriet died.

How did it come to this? We can only spy the character of each through the few surviving records. Maxime may have been violent or a poor provider, but his mother’s last will and testament, signed nearly thirty years later, specifically acknowledged his tender care and support in her declining years. She went even further by excluding her other children from the succession. As for Harriet, in her final months, she seemed to be of two minds: she repeatedly threatened to leave before taking the ultimate step. Once set on an idea, she committed to it. Before the lethal abortion, she consumed ergot (another abortifacient) and jumped to try to expel the fetus. As for her mother, Alice Titus, days into the investigation, a Burlington newspaper reported that

[s]he had always been an element of discord in her daughter’s family, and had been frequently turned out of the house by Mr. Gaudette to rid himself of an open enemy to his peace. It is charged that she has for some time kept a house of ill-fame at Rutland, and had tried every wile to persuade her daughter to leave her husband and join her at her infamous establishment. Mrs. Gaudette at last yielded, and lost her life in her efforts to escape the encumbrance of another child.

We are unlikely to know whether the paper found that it could spread baseless rumors with impunity, though the mere mention of abortion might, in an editor’s mind, justify interrogating the moral character of the female parties. Inequitable treatment of the genders appeared in other ways, too.

In light of nineteenth-century medicine, unsanitary practices and infections took an untold number of lives. With abortions, many women died instantly (perhaps from shock) or within days (likely from unresolved hemorrhaging). That, more than anything else, is the recurring theme in these stories. Women were always the ones to pay the cost of an unwanted pregnancy. If they did not pay it in terms of social standing, they did physically. The indignity of disinterment and postmortem examination was nothing as compared to the treatment afforded to them by men who performed high-risk procedures and essentially experimented on them. Whatever the legal outcome, the men involved in these cases—particularly fathers and physicians—would walk away.

Less than a month after Harriet Gaudette’s death came that of Eliza McMahon of West Rutland. She was a housekeeper for Daniel Conway, the presumed father, who was more than twice her age. Then, in the spring of 1878, the press learned of the death of Caroline Bettis, “a French girl of Williston.” Her passing came about eight days after the operation she had sought. The press commented on her character more pointedly than with other victims of abortion. An unmarried woman, she had had an illegitimate child two years prior. With both pregnancies, the presumed father was George Bombard, a day laborer boarding with the Bettis family.

So, what of the fathers and physicians? There were consequences, but perhaps not as we would expect. The William Howard responsible for the Young and Ash deaths was arrested. His bail was set at $600, the entire amount of which was supplied by Howard’s friends. Public opinion—i.e. newspapers—might be vehement in denouncing abortion practitioners, yet, at a local level, such figures had their share of personal supporters willing to turn a blind eye and help them evade the law.

Howard was an especially notorious character. He had lived in various places in Canada and the United States under assumed names. In Burlington, he defrauded merchants. He claimed (dubiously) to have served as a surgeon with the British army; that seemed to suffice in drawing him a clientele in Bradford. In the Ash case, he escaped a charge of manslaughter. A county court then indicted him for the intent to procure an abortion. He appealed, enabling him to remain free on a $1,500 bond, which he again supplied with assistance. He failed to appear at a first court session in Montpelier. When at last he did appear, in November 1859, the court promptly sentenced him to two years of hard labor in the state penitentiary.

Mattie Spaulding, for her part, saw a Dr. Streeter, who, as the investigation began, was nowhere to be found. A newspaper stated simply “that on account of some of the parties being influential the case will be hushed up.” A similar conspiracy of silence may have been at play in the Leafy Brown case. There seemed to be general agreement as to the responsible parties, but, a paper reported cryptically, there was insufficient evidence to bring the case to trial.

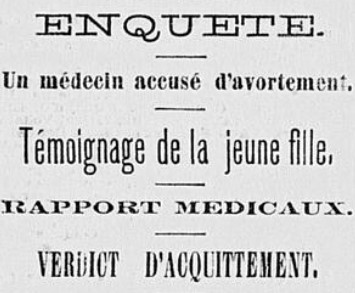

The hand of influential figures was also at play in the wake of Harriet Gaudette’s death. A letter to the press stated that physicians could not be held responsible for patients’ moral character. Signing “Old Times Rocks,” the correspondent claimed it was Gaudette who destroyed the fetus; he or she then assailed the local official who issued the warrant. We hear little of Dr. Haynes, whom Gaudette had seen, for some time—partly because the judicial mechanisms of Vermont were far from ensuring a speedy trial in the nineteenth century. More than fifteen months after Gaudette’s death, the case still stood before the courts, though, according to a Springfield paper, the charges “will probably be dropped.” As for fathers, Daniel Conway and George Bombard were both arrested, but only a deeper dive into judicial archives will reveal their fates.

These eight names broke into the press because the women died and people spoke up. No doubt others died—and the people with illicit knowledge or suspicions chose to remain silent. It is also certain that a large number sought an abortion, underwent the procedure, and survived. Abortion is not a product of the second half of the twentieth century or of its legalization.

The historical record is complex and multilayered. It involves trysts, sexual violence, bad marriages, and difficult situations made worse by silences and the threat of moral and legal sanction. It involves clear power differentials between men and women. It involves incompetent physicians and well-meaning physicians—and physicians who were both. It involves grieving friends and families. It involves knowledge networks and protectors: women looking out for one another, lovers seeking to avoid social condemnation, perhaps even influential people willing to protect physicians specifically because they performed abortions.

Historical facts can be spun to teach all sorts of lessons. Few of us are immune to the temptation of seeing analogies to our own time in past events, or plucking from the past that which best fits our values. The greatest virtue of historical study may instead lie in deepening our appreciation for people who lived in a vastly different world, yet still felt what we feel. We are doing ourselves a great deal of good in extending acts of sympathy and commiseration to people who long preceded us—all the more so if we make such acts a habit in the present day and build a society and institutions around them.

Lucina Young. Olive Ash. Leafy Brown. Lydia Chase Cook. Mattie Spaulding. Harriet Titus Gaudette. Eliza McMahon. Caroline Bettis.

Sources

Newspapers:

- Argus and Patriot (Montpelier, Vt.), December 19, 1877

- Burlington Free Press / Free Press and Times, February 19, 1858; March 25, 1872; December 11-13, 15, 17-18, 1877; January 10, 1878; June 8, 1878; October 14, 1879

- Caledonian (St. Johnsbury, Vt.), February 13, 1858

- Democrat and Weekly Sentinel (Burlington, Vt.), December 22, 1877; June 8, 1878

- Middlebury Register, December 21, 1877

- Rutland Daily Globe, August 28, 1874

- Springfield Reporter, March 28, 1879

- Vermont Phoenix (Brattleboro, Vt.), November 26, 1859

- Vermont Watchman & State Journal (Montpelier, Vt.), December 17, 1858

Additional information about these individuals was gleaned from Ancestry.com and FamilySearch collections.

Leave a Reply