See Part I here.

Others emigrate freely with their families, driven by poverty or despair, as, in fact, has been done for many years despite the efforts of governments and friends of domestic colonization. All of this owes to causes that are separate from what we are presently discussing; we only mention it to highlight the injustice of those who falsely attribute to the government the migratory movement to the United States and who would make recruiting agents for the Union Army the sole cause of emigration.

– Le Pays, January 30, 1864

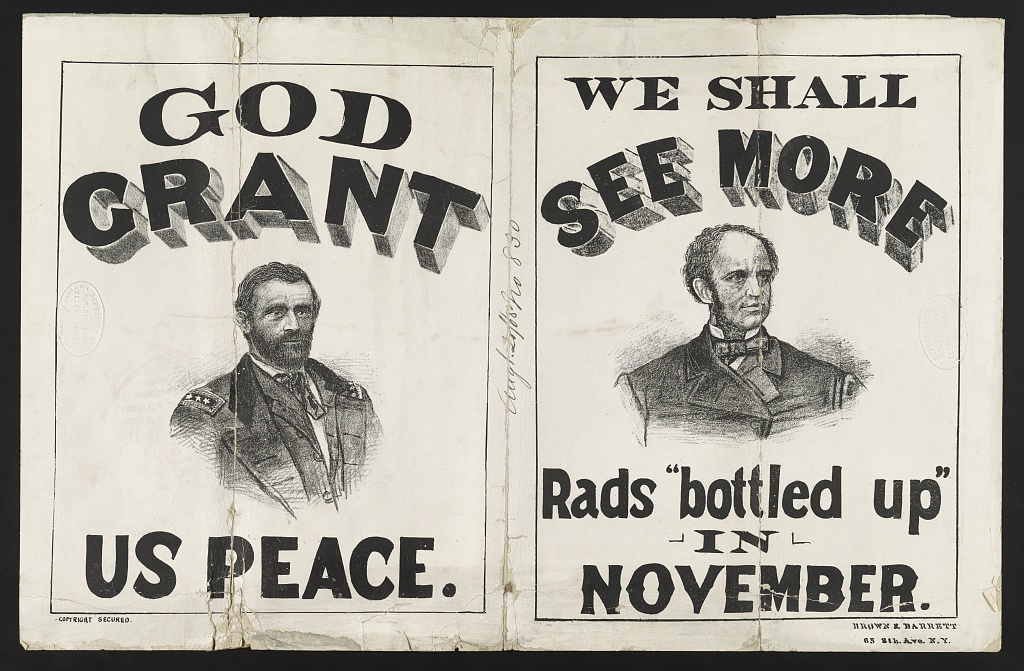

The U.S. Civil War disrupted everything. It is little wonder that it usually marks the cut-off between early and modern American history courses at the college level. The conflict permanently altered the American economy and ushered a new phase of industrial capitalism. The challenges of the South’s readmission to the Union and race relations replaced the divisive issue of slavery. The Republican Party, which had won the presidency for the first time in 1860, was now in the ascendency. It would only lose two presidential elections from 1860 to 1908.

On the other hand, this easy before-and-after dichotomy conceals significant elements of continuity. The dispossession of Indigenous nations did not relent. Beginning with famine-era Irish immigrants in the 1840s, the country grappled with mass immigration and the integration of peoples with different traditions, languages, religious beliefs, and economic and political concerns. Further, this remained a deeply Protestant country, which various social crusades and legislation reflected. The New Hampshire Constitution barred non-Protestants from the governorship until 1877, for instance.

That is national history—now for the transnational part. The Civil War disrupted the flow of French-Canadian immigration. But it may have been a blip, making only a slight dent in an overall trend.

Lower Canada experienced a high rate of emigration in the 1840s and 1850s. Vermont and New York State were by far the most significant destinations in this period. Entire family units migrated and heads of household found work as farm workers, tradesmen, and unskilled laborers. They settled in rural areas and small towns. Industrial pursuits became more common—in Winooski, Vermont, for instance, where a woolen mill had gone up in the 1830s. Gradually, migrants learned of opportunities farther afield. The Canadian press mentioned Lowell, Massachusetts, and Manchester, New Hampshire, as destinations as early as the 1840s. In Salmon Falls (present-day Rollinsford), New Hampshire, mills attracted a small group of French-Canadian women who were known to return to Canada with their savings. Recognizable immigrant communities also emerged in Woonsocket, Rhode Island; Biddeford, Maine; and Southbridge, Massachusetts, each of which had more than 500 French-Canadian residents by 1860.

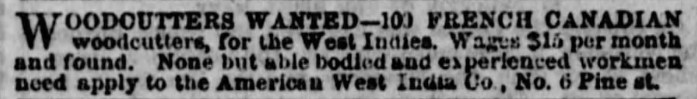

Then there was recruitment—industrial recruitment. The Dwight Manufacturing Company of Chicopee, Massachusetts, sought out French Canadians at the end of the 1850s. One of its recruiters came highly recommended from the mills in Salmon Falls and his work paid off with the arrival of a first contingent of French-Canadian women in 1859. Managers in neighboring Holyoke sent their own agents, creating an interesting rivalry between American corporations. In 1859, the Holyoke agents are said to have hired workers in Saint-Césaire and to have been active in the Eastern Townships.

The Civil War initially disrupted textile manufacturing. Thousands of workers were let go in Baltic, Connecticut, and in Holyoke, and one observer stated that 7,000 Canadians returned home in the spring of 1861 due to a war-related hiatus in production. Women in Holyoke were said to be dispersing in their search for income; though efforts were under way to bring them back into the mills, the workers were, according to one correspondent, risking privations and dishonor.

Beginning in 1863, thanks in part to war orders, industry recovered and experienced labor shortages. French Canadians answered the call. In an 1863 report, Joseph H. Daley argued that the renewed exodus was not as dramatic as rumored. Nonetheless, he recognized that the number of people leaving had begun to climb again. This migration, Daley stated, was distinct from what had come before. Since the 1840s, young men had gone south to work in brickyards and mills in the summer and spent their winters with family in Canada. Now they were being asked to replace native-born Americans—currently serving their country—in lumber camps through the winter months. We may wonder whether Daley purposefully skirted the question of industrial opportunities.

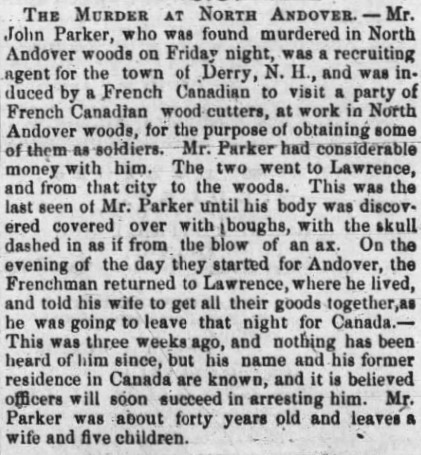

Daley’s remarks were mirrored in a December 1863 article in the Gazette des campagnes, which had observed a resumption of emigration fever. But, in this report, mill recruiters were the true agents of expatriation. The luster of these lofty promises quickly disappeared as emigrants reached the manufacturing cities of the Northeast. In fact, that very month, seventeen families from Saint-Aimé on the Yamaska River left to work in factories until the spring thaw, when farm work would resume—a high-risk endeavor if a contemporary pause in production in Lowell was any indication. Then, a report from Belfast, Maine, indicated that French-Canadian men recruited for civilian work, but ultimately left to their own devices, had had no choice but to enlist in the armed forces. In the summer of 1865, the press assailed a man named Proulx who had recruited families from Richelieu and Yamaska counties but had deserted them upon their arrival in Montreal, where they were to be taken by rail to American factories. When families did arrive in U.S. cities, they had to contend with production woes. Even when cotton supplies stabilized, the price of the raw material was sometimes prohibitive and unlikely to be made up by consumer demand—and so mill bosses would suspend operations again. Still, such realities were not enough to slow the demographic hemorrhage.

Most sectors of the Northern economy were in need of labor. A Colonel Lagrave of Ste Genevieve traveled to Lower Canada to recruit French Canadians to work in Missouri mines in the summer of 1863. More than 200 accepted the invitation; many men migrated with their families. At Iron Mountain and Lagrave’s Mines, they extracted iron ore and worked the furnaces. According to one contemporary newspaper, “they are about the best hands ever employed at the works . . . and none of them can speak English” (Cleveland Daily Leader, March 31, 1864).

Emigration clearly occurred in the second half of the war, but the effective victory of the Union in the spring of 1865 released the floodgates. In June, the Gazette de Sorel carried excerpts of various Lower Canadian newspapers which had made that very point. The district east of Saint-Hyacinthe, including Saint-Pie, Roxton, and Acton, struggled with depopulation, with rising municipal taxes being mentioned as further incentive to leave. According to one paper,

Parishes that have only just been established are now being emptied at a frightening rate due to the emigration fever that has seized our rural populations. It is as though the misfortunes that befell the American Republic have given it a new charm in our compatriots’ minds. The bloodletting of this civil war has not yet been stanched yet already our compatriots are rushing with incomprehensible energy to this battered land. (Gazette de Sorel, June 17, 1865)

La Minerve followed several months later with a report from Woonsocket. The migrants in that city were sinking into religious indifference while struggling against taxing work, the high cost of living, and little opportunity for advancement. This, the author stated, was comparable to the rush of Canadians to California in the wake of the gold rush. The migrants had taken more money out of Canada than they had brought back. Few exiles had themselves returned, in fact. Evidently, the streets of Woonsocket were no more gilded than those of San Francisco.

The warnings fell on deaf ears. The Civil War had at best temporarily suspended the high levels of emigration of the 1840s and 1850s. The Canadiens and Canadiennes were needed just as before. While the United States met the drama of national reunification, racial justice, and Reconstruction, a transnational epic continued to play out across the northern boundary.

A Note on Sources

See, for Canadian reports of emigration beyond those cited above, Montreal Witness, October 1, 1859; La Minerve, October 10, 1861; Gazette des campagnes, December 1, 1863; L’Ordre, December 28, 1863; Courrier du Canada, June 8, 1864; Journal de Québec, July 6, 1865; and La Minerve, September 9, 1865. See also New York Daily Herald, January 28, 1860 and Fall River Daily Evening News, August 13, 1864.

The essential sources for this period are Jean Lamarre’s book on the Civil War, mentioned in the previous post, and Ralph D. Vicero’s doctoral dissertation on French-Canadian migrations prior to 1900 (1968). François Weil discusses industrial recruitment activities in an excellent synthesis, Les Franco-Américains: 1860-1980 (1989). A lesser-known, slightly more antiquarian work is Marie-Louise Bonier’s Débuts de la colonie franco-américaine de Woonsocket, Rhode Island (1920).

Pingback: Friday’s Family History Finds | Empty Branches on the Family Tree

Pingback: This week's crème de la crème - February 17, 2024 - Genealogy à la carteGenealogy à la carte