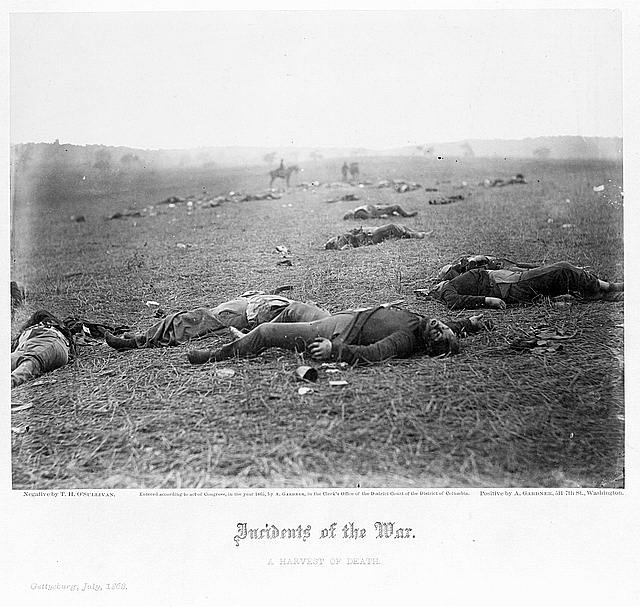

Private Sylvester Turner’s experiences during the War of the Rebellion are probably lost to time. But those experiences were undoubtedly trying, complex, and sobering. The Second Vermont Infantry with which Turner served fought in some of the bloodiest engagements of the war, including Antietam and Gettysburg. In fact, the Vermont Brigade had an unequalled casualty rate. If the loss of comrade-in-arms is not enough to underscore Turner’s good fortune in surviving the war, we might think of another Sylvester Turner—a soldier of the same name who served with an Illinois regiment and died of gangrene at the notorious Confederate prison in Andersonville.

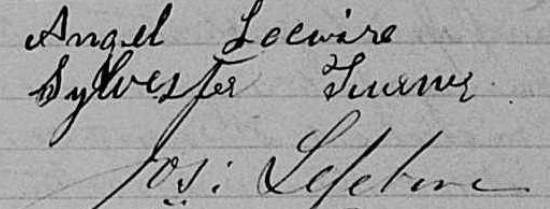

The Turner with whom we are concerned served three years and returned to his ancestral homeland, Lower Canada. This is in fact the Cyprien Létourneau we met in the last blog post. Undoubtedly a changed man, he rejoined his parents, who had left northern Vermont to settle in the Eastern Townships. He married Angélique Lacroix in 1869. Not one child was born of the marriage. In 1887, three weeks after his father’s death, Sylvester filed a request for an invalid’s pension from the U.S. government, as though he had still depended, to an extent, on his parents’ support or means. He himself died in 1890, aged only 50. Was all of this the product of wartime scars, either physical or mental?

Many of the specifics of the war—as it touched thousands of individual French-Canadian lives—have gone unremembered. But contemporary reports, the memoirs of survivors, and aggregate data about soldiers and officers enable us to speculate and form an overall picture of the conflict. Journalist Rémi Tremblay, a veteran of the war, later published a novel inspired by his experiences. A Montreal newspaper aptly stated that the course of events in Tremblay’s Un Revenant “belongs to American history by its stage, but belongs to ours by virtue of the actors who played upon it” (La Presse, January 7, 1885, transl.).

How many actors, exactly? In the aftermath of the Civil War, some political and religious leaders in Quebec stated that 40,000 French Canadians had joined the ranks. Historians have since had their say. In the 1950s and 1960s, Robin Winks, Robert Rumilly, and Ralph Vicero found the figure of 40,000 much too high, but did not risk putting forth numbers of their own. Building on Danny Jenkins’ master’s thesis, historian Jean Lamarre has estimated that between 10,000 and 15,000 French Canadians who were already residing on U.S. soil in 1860 served in the war. The migrants who crossed the border during the war and enlisted would raise the estimate, but still leave it well short of the earliest stated figure. (Lamarre’s book is at this time the most definitive work on French-Canadian participation in the Civil War.)

French-Canadian veterans earned fame, but few specifically for their service. Calixa Lavallée is known today as the composer of O Canada. Many Franco-Americans will recognize Edmond Mallet’s name; he became a figurehead of his ethnic community in the 1880s. Rémi Tremblay was well-known as a journalist in his own day. Significantly, like our friend Sylvester Turner, all three had lived in the United States prior to the beginning of the war. Prosper Bender, for his part, migrated during the war and served as a surgeon in its final months.[1]

French-Canadian volunteers had an average age of 25—just like their American counterparts—and most were single, with little education, and originated from the southern regions of Lower Canada. They were, in these respects, not particularly different from the young people who ventured away from home and sought civilian work in the middle part of the nineteenth century. Though a taste for adventure and ideological preoccupations may have led some men into the ranks, military service was essentially another survival strategy. There is evidence that the economic status of emigrants on U.S. soil had fallen during the 1850s; enrollment might have come from a place of desperation among men who could not envisage better prospects in the old homeland.

Lower Canadian leaders regretted that many of their own people were willing to shed their blood for another nation and for a cause that was not theirs. But French-Canadian enlistments also became a public issue due to reports of recruitment activities north of the international boundary.

More than three years into the war, the U.S. Senate asked the president

if any authority has been given to any one, either in this country or elsewhere, to obtain recruits in Ireland or Canada for our army or navy; and whether any such recruits have been obtained, or whether, to the knowledge of the government, Irishmen or Canadians have been induced to emigrate to this country in order to be recruited; and if so, what measures, if any, have been adopted in order to arrest such conduct.

Secretary of State William Seward declared that no such authority was given. “[W]henever application for such authority has been made it has been refused and absolutely withheld,” Seward stated. He added:

In two or three instances it has been reported to this department that recruiting agents crossed the Canadian frontier, without authority, with a view to engage recruits or reclaim deserters. The complaints thus made were immediately investigated, the proceedings of such recruiting agents were promptly disavowed and condemned, the recruits or deserters, if any had been brought into the United States, were at once returned, and the offending agents were dismissed from the public service. (New York Herald, July 1, 1864)

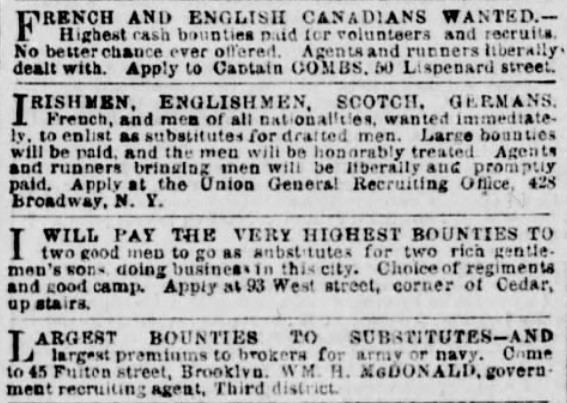

Although not so much as in the Mexican-American War, immigrants from British North America and Europe (who enlisted voluntarily after immigrating) did constitute a large share of the U.S. army and naval forces. Efforts to bring newcomers into the ranks and word of mouth in diasporic communities may have blurred the line of foreign recruitment.

Nevertheless, there were recurrent reports, some more substantiated than others, of recruiting activities in Lower Canada.[2]

According to several newspapers, a French-Canadian man by the name of Lavigne hired three compatriots ostensibly to work in the lumber camps of Gorham, New Hampshire; once in Island Pond, Vermont, the unsuspecting workers signed documents that they did not understand, after which they were put in uniforms and sent by force to Boston. Liberal leader Antoine-Aimé Dorion, then attorney general for Canada East, downplayed such stories and argued that legal means of redress were few.

The Montreal-based Le Pays published circulars sent by the bishops of Quebec and Saint-Hyacinthe to priests of their dioceses concerning emigration. Both letters touched on the problem of military recruitment in the St. Lawrence valley. They denounced American agents and enjoined priests to keep their flocks from falling prey to ruses. “On behalf of their dearest interests,” Bishop Joseph La Rocque stated, “encourage [parishioners] to listen to wise counsel; positively prevent them from exposing themselves to the imminent risk of losing life in a foreign land or yet wasting their health and returning—injured or sick—to lead a miserable existence to the end of their days.” La Rocque claimed that authorities had already arrested 25 to 30 agents operating in the Eastern Townships.

In the following issue, a Pays writer editorialized. English-language newspapers in Montreal were agitating the foreign recruitment issue to score political points against the sitting government in Canada. But there was more to it. Those papers seemed to be more favorable to the Confederacy and therefore had a special reason to look with contempt on Northern agents. Le Pays conceded that with such an open border as that between the Canadas and the United States, little could be done to stop American agents. Beyond finding and apprehending those agents, public figures in Lower Canada had as their main weapon moral suasion.

The writer was undoubtedly correct about the relative powerlessness of Canadian authorities in the face of U.S. recruitment activities—though the agents were likely rogues and their presence, exaggerated. They may have been private agents seeking substitutes for wealthy draftees. The writer made, in passing, a point of much greater import. The press ought to worry a lot less about military recruitment than about the emigration of families to work in Northeastern mills and infrastructure projects. That, as we will see in the next post, remained the most pressing issue when it came to French Canadians crossing the border in the era of the U.S. Civil War.

A Note on Sources

See, on Canadian reports of recruitment, L’Ordre, December 11, 1861; Gazette des campagnes, December 1, 1863; Le Pays, January 28 and January 30, 1864; L’Ordre, March 11, 1864; L’Echo du Cabinet de lecture paroissial de Montréal, December 1864.

For more on the Canadas during and after the Civil War, see Part I and Part II on Ulysses S. Grant’s travels in Canada as well as my post on Jefferson Davis’s northern exile.

[1] Honoré Beaugrand and Faucher de Saint-Maurice also fought abroad in the 1860s. However, they supported France’s imperial efforts in Mexico.

[2] A Canadian correspondent shared with American outlets news of Confederate recruitment activities north of the border. Rebel agents were inducing Canadians to sign up and then sending them to Baltimore. The Canadians were then expected to desert to the Southern side. Whether this was a realistic scheme is debatable at best; in any event, this report came at the end of 1864, when the Confederacy’s chances of victory were verging on non-existent. (Pittsburgh Gazette, December 22, 1864)

Was there recruitment & enlistment on both sides of the St. John River Valley? Is there a list of soldiers? Especially interest in Saint Basile, St. Leonard Parent, Madawaska, Van Buren, & Hamlin.

Hi Nancy. We don’t have a comprehensive database of Civil War soldiers and officers from the Upper St. John Valley. The best sources remain Ancestry.com and Fold3. But we do have local lists compiled from cemeteries and other town records. At the Acadian Archives, a list from Fort Kent compiled by Claude Charette shows that the majority of local soldiers were of non-French background. However, there were Eli Busha, Firmin Caron, James Charette, and Albert and Joseph Thibodeau. In the Van Buren cemetery, there are Civil War markers for Peter [Pierre] Castonguay, Joseph D. Cyr, Thomas [Damase?] Thibodeau, and Thomas [Damase?] Violette. In Saint-David, André Francoeur has a similar marker. I haven’t come across similar records on the Canadian side. The most comprehensive work on the history of the Valley, Craig and Dagenais’s Land in Between, does not address enlistments from the region, so I think there’s significant research still to be done on the war’s impact in northern Maine.