Book Review

Caroline B. Brettell. Following Father Chiniquy: Immigration, Religious Schism, and Social Change in Nineteenth-Century Illinois. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2015.

Regular readers of this blog will recognize that it is chiefly concerned with the Franco-Americans of New England and New York State and their connection to Quebec history, with occasional attention to the Acadians (more to come in that regard).

This focus should not diminish the historical significance of the French Canadians who settled in the American Midwest and West. In the study of French North America, research on the northeastern Franco-Americans easily obscures other segments of the diaspora; this owes no doubt to the first group’s geographical concentration and its proximity to the ancestral homeland. Historical scholarship on French-Canadian communities in other parts of the United States still fares well, however—to say nothing of French Canadians in Ontario and the western provinces. The work of Jean Lamarre, Jay Gitlin, Robert Englebert, Guillaume Teasdale, and others attests to that fact.

It is in this context that Caroline Brettell’s Following Father Chiniquy appeared in 2015. Brettell, a professor at Southern Methodist University, is a distinguished scholar of immigration with personal connections to Montreal and Illinois. Though the book has been available for years and makes an important contribution to our understanding of Franco-America, it has perhaps not received the attention it deserves.

Brettell is quick to acknowledge that New England gets much of the attention in the realm of Franco-American studies. She sees this standard focus as a point of departure for comparison, as she turns her gaze westward to French-Canadian immigrants in Illinois. “These immigrants to the Midwest,” she states, “encountered a frontier rather than a Yankee stronghold. They participated in the formation of a culture rather than a struggle against absorption by one that was already formed. Their populations were not constantly renewed as were those in New England.” (7) In addition, the migrants settling in the Midwest were preserving a traditional agrarian lifestyle; when such economic opportunities disappeared, immigration ceased.

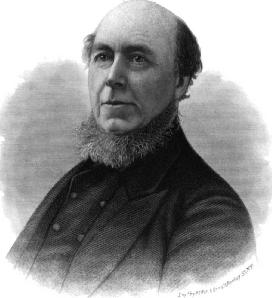

The first half of Brettell’s book is organized around Charles Chiniquy, born in Kamouraska, in Lower Canada, in 1809. Chiniquy joined the Catholic clergy and became the pastor in Kamouraska in the 1840s. He quickly lost his charge due to an alleged liaison with a parishioner. He relocated to Montreal, where he became a leader in the temperance movement. Despite the closer scrutiny of Ignace Bourget, the powerful Catholic bishop of Montreal, new rumors swirled around Chiniquy. The priest was a proud man who made immoderate remarks; buoyed by his own oratory and popularity, he was turning into a loose cannon. Allegations of romantic and sexual impropriety sealed his fate. In the fall of 1851, Bourget cut him loose. Chiniquy went west and was welcomed by Bishop J. O. Van de Velde of Chicago. (Our controversial figure had visited the west before and submitted thoughts to the government committee on emigration at the end of the 1840s.)

Agitation followed Chiniquy. In Chapter 2, Brettell points to factors of discord between the priest (and to a lesser extent the Illinois French settlers) and Van de Velde’s successor, the predictably Irish Anthony O’Regan. The latter moved a church building attended by the French and installed an Irish pastor. Questions and conflicts emerged over responsibility for supporting the church. In that, O’Regan’s decisions and the French reaction anticipated what would happen generations later in Fall River and in Maine.

O’Regan suspended and excommunicated Chiniquy in 1856—and Bourget supported his fellow bishop. Worn down by controversy, O’Regan resigned soon thereafter. The new bishop, James Duggan, followed through on the excommunication order. Chiniquy was undeterred. He remained as a spiritual leader of the Illinois settlers; a large majority of his congregants continued to support him. The whole affair played into Catholic-Protestant tensions in Quebec and into the religious and ethnic nativism of the Know-Nothing era. When crops failed in northeastern Illinois at the end of the 1850s, Chiniquy left to draw support elsewhere; Eastern Protestants quickly responded with generous donations in support of the renegade priest and his community. It seemed as though Chiniquy and American Protestantism had saved the community, reinforcing the spiritual leader’s almost messianic image. Already a de facto Protestant, he formally joined the Presbyterians in 1860, though even in that fold controversies and tensions emerged from time to time. A war of words would continue between the Catholic Church and Chiniquy—much of it wrapped in sexual innuendo—until his death in 1899.

The author explores the condition of “liminality” that led so many French-Canadian immigrants with an unimpeachable Catholic past to follow Chiniquy—and, really, the conditions that could make the emergence of such a powerful charismatic figure possible. Brettell connects him to other historical figures who mobilized religion (or religion of a kind) to such significant ends—but in references to Robespierre, Franklin Roosevelt, and Jim Jones, we sense that the comparison may at times be strained and may be minimizing the unique realities of mid-century Franco-American settlements.

The remainder of the book takes us away from Chiniquy and reads as a series of distinct essays that analyze the French communities of Illinois from different standpoints. The most illuminating chapter to readers with an interest in French-Canadian migrations may be the fourth, where Brettell shows she is no blind follower of the “great man” theory of history. Following common people, their family situation, and their migrant journey, she names names and provides indepth demographic and economic analysis of the French-Canadian settlement.

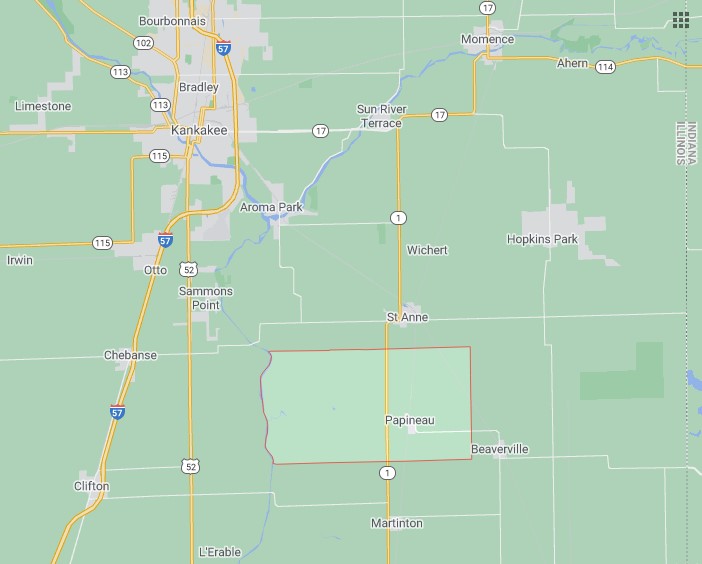

The pull of Illinois was largely over by the beginning of the U.S. Civil War; soon, the French in that state would feel another pull, this one to Kansas. Many enjoyed success as commercial farmers there. “[D]espite this successful economic assimilation,” Brettell writes, “they maintained aspects of their French Canadian identity, and as in Illinois, the French language did not disappear until the 1920s. Today, family names in the telephone directories of Clay and Cloud Counties [in Kansas] resemble those in Kankakee and Iroquois Counties.” (127) In both areas, there was remarkable (perhaps surprising) cultural and ethnic preservation as well as community stability.

Even by the end of the book, Brettell’s focus is ill-defined. The last two chapters flirt with legal history, race relations following the Second World War, and the ritual and community life of the Catholic parish of St. Anne. Chiniquy is hardly mentioned. On the other hand, the strengths of Brettell’s work are undeniable. To scholars, she offers a sound theoretical exploration of ethnicity, “social drama” (based on the work of Victor Turner), and charismatic leadership. The anthropologist shines through in these sections.

To casual readers, history buffs, and historians, the significance of the work lies not in Chiniquy’s local legacy in St. Anne, Illinois, or in dissemination of Chiniquy’s polemics still today by extreme anti-Catholic groups. The real endpoint is in the question Brettell raises in the introduction—whether assimilation happened differently, or meant different things, in the East and the West.

Admittedly, as the book suggests, assimilation is a problematic concept—it is seen as unidirectional, seemingly inescapable once under way, and one-sided. It is understood as the erasure of distinct ethnic characteristics and the absorption into the majority culture. Analysis of demographics, community life, and cultural survival in rural Illinois (not to mention Protestantization) hints at a situation too complex to fit this understanding of assimilation. There, for generations, one could be French-Canadian, but a different kind of French Canadian, the likes of which we do not see in Quebec and New England, a community that challenges stereotypes and inherited identity categories.

This is the second book review on the QTP blog. Read the first, addressing a study of Franco-Americans in the Champlain Valley, here.

As a descendent of Cloud County, Kansas, French-Canadian immigrants, I had long heard of the religious schism between the French Catholics and the French-Presbyterians, the latter being the followers of Fr. Chiniquy. For example, I have heard from other descendents that many of the French-Presbyterians blamed the French Catholics for burning down their Cloud County church in the late 1800’s. (Cause of fired was never determined) Such was the split, that I can recall that my father insisted his family (who were followers of the Chiniquy sect) was not Catholic, although his parents were all baptized Catholic in Canada.

Small pockets of the French language remained into the 1960’s. I can remember some of the old farmers, who gathered at the local grain elevator that my father managed, speaking in French to each other and In the course of conducting business some of the older farmers (who spoke some English) would sometimes speak to my father in French. He being the youngest member of his French family did not speak much French but apparently understood them . . . although he would answer them in English. In retrospect, these French/English conversations would seem rather comical today.

Wow, thanks so much for sharing these stories, Janet! Fascinating!

Correct on last name: Janet K Cyr!!!

I have a huge antique portrait of Rev. Chiniquy in an elaborate hand Carved frame with wood slat backing that I bought at an estate sale in Crete Illinois. Anyone interested?