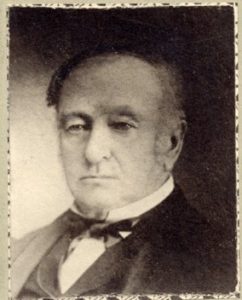

Several months ago I provided a brief glimpse of the life and times of Prosper Bender (1844-1917), a Quebec-born physician, littérateur, and intercultural broker.

Bender spent much of his life championing unpopular causes. Though he may have delighted in being a contrarian, there is little to suggest that he was a girouette, a weather vane. Ceaselessly he endeavored to bridge the misconceptions and suspicions separating French Canadians and their English-speaking neighbors. His body of work remains as relevant today as it was in the late nineteenth century. It continues to illuminate the challenges facing the young Canadian federation, suggesting that the British North America Act could have proven as short-lived as prior constitutions. More significantly, it points to the never-ending task of fostering amicable relations amid cultural differences.

The street stretches southwesterly from the ramparts of the Upper Town, only a short walk from the National Assembly. There Bender made his home and saw patients—perhaps for a decade, perhaps more—before he abruptly moved to Boston in 1882.

If the latter location does, through further research, prove to be Bender’s former residence, we hope to have the City of Quebec honor him with one of its “Ici vécut” historical plaques, such as the one gracing Faucher’s house.

As for his lengthy stay in Boston, extending to 1908, Bender’s whereabouts require much less speculation. Perhaps from the moment of his move, he lodged at the prestigious Hotel Vendome on Commonwealth Avenue. Although not necessarily an evident choice for him, Bender had previously visited the Northeast; he was preceded in Boston by other Canadian intellectuals who may have whetted his appetite. What is clear is that he quickly found his footing there, even joining a committee venturing to organize an international exhibition in the city. A decade later, having nearly fulfilled residency requirements for naturalization, he related an anecdote that expressed his view of the great Yankee hub:

A woman who had just lost her husband desired to have a tombstone placed over his grave, with some choice inscription, and she requested suggestions to that effect. Several were submitted to her taste, but all failed to meet its fastidious requirements. Finally the supply of sentiment being somewhat exhausted, it was asked if she would not like the simple, old epitaph: “Gone to a Better Land.” “Oh! no,” she quickly replied, in a tone of surprise, mingled with some indignation, “that would never do; why he lived all his life in Boston!”

– Bender in The New England Magazine (1892)

As for the Vendome, it was a sought-after address; within its halls were held grand dinners organized by and for the well-to-do (see here and here). Well after Bender’s departure, following the Second World War, other hotels began to eclipse it. At the turn of the 1970s, renovations that would convert the hotel into luxury apartments promised the building a new lease on life. But in the course of these renovations the Vendome earned the infamy with which it is still associated: a fire broke out in June 1972 and in battling the blaze nine firefighters lost their lives, the deadliest day in the history of the Boston Fire Department. With reason, the likes of Bender who called the Vendome home have largely been obscured.

One can easily read too much into Bender from his place in turn-of-the-century urban geographies. Both he and Faucher tell of long rides with friends into the countryside around Quebec City; there was a deep affection for those rural landscapes and their people. They provided inspiration to Bender in his writing.

It remains no less that on d’Aiguillon his salon served as the synapse of French-Canadian intellectual and cultural life. In Massachusetts, he may have become one of those individuals who, according to Thomas D’Arcy McGee, assumed “Bostonian culture to be the worship of the future, and the American democratic system to be the manifestly destined form of government for all the civilized world, new as well as old.” Boston was indeed a center of culture. Ever ready to play the contrarian, Bender sought to be where ideas circulated, where power was exerted. In both locations, we know that he lived in luxury, truly inhabiting the role of a middle-class man-about-town.

You can learn more about Bender in “Seeking an ‘Entente Cordiale’: Prosper Bender, French Canada, and Intercultural Brokership in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Canadian Studies (spring 2018), 381-403, accessible here.

Addendum, December 2018: Since writing this, I have had the pleasure of hearing from Quebec City’s Service de la culture, du patrimoine et des relations internationales. Quite helpfully, some diligent public servants undertook research and found that Bender’s home was actually at the corner of Saint-Augustin and d’Aiguillon in the 1870s, a building that no longer exists. Nevertheless, Bender is now in the Quebec City database from which the names of streets and other public landmarks are drawn. He may yet have his day in the sun.

Leave a Reply