Frequent readers of the blog may roll their eyes here: New York State deserves greater attention and study in the field of Franco-American history. It is a case I have made before; every now and then, I put my money where my mouth (or pen… or keyboard) is and try to make some humble contribution in that direction, whether on this blog or in academic venues. Here we are again.

Most works on French Canadians in the U.S. focus on the New England states; some, on the Midwest. Admittedly, though, research on Franco-Americans in New York is not an utter historiographical desert and I would not wish to diminish the work of those who have sought to rescue from obscurity the experience of this minority population. At a local level, Bernard Ouimet has devoted many years to the preservation of the French-Canadian past in Cohoes. Daniel Walkowitz wrote an influential study on labor relations among American ethnics in Cohoes and Troy. Cynthia Fox has written on language preservation in New York State.

Research has appeared in other guises. There is the grassroots FeFANY in the Albany area and the Northern New York American-Canadian Genealogical Society based in Dannemora. Janet Shideler (Siena College) recently launched the Je Me Souviens Project. Additionally, in 2018, Arcadia published an important contribution to the history of the Champlain Valley, spanning both sides of the lake.

The premise here, of course, is that we cannot simply take what we know about the Franco-Americans of New England and apply it wholesale to other states—that there is something unique to many New York communities that is in itself worthy of study and that can enrich our larger understanding of the French-Canadian diaspora.

In that spirit, let’s consider, briefly, Cohoes (Cuh-HOSE), a city located almost exactly half-way between Plattsburgh and New York City, and barely an hour’s drive from Bennington, Vermont. As with many industrial cities, we must consider its physical environment to appreciate its significance. Cohoes rose where the Mohawk River plunges and then meets with the Hudson. The construction of the Erie Canal, which ran through the city as it neared its eastern endpoint, helped to secure the area’s commercial relevance. But it was the Mohawk falls and their power-generating potential that brought industry.

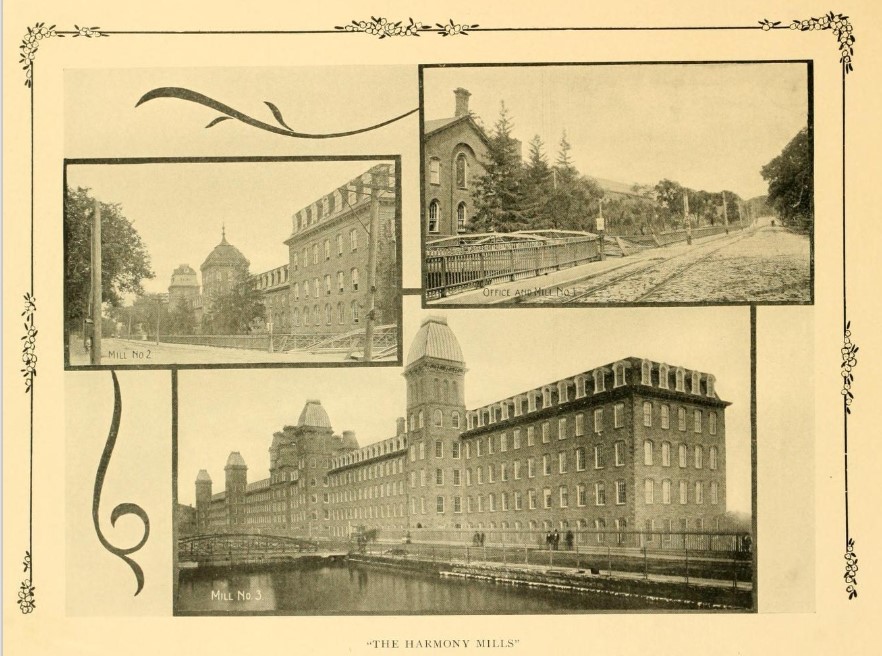

The Harmony Manufacturing Company, a cotton concern founded in 1836, took advantage of the falls to drive production. The company struggled in its first decades, but hit its stride at the time of the U.S. Civil War, when it began to absorb local woolen mills. Afterwards, Daniel Walkowitz explains, “Cohoes became a ‘company town,’ possessing for a time in the 1870s the largest cotton mill in the world, the Harmony Mills’ ‘Mastodon’ (No. 3) Mill . . . Cohoes’s Harmony Mills, with 5,000 operatives, constituted one of the nation’s largest textile firms, dominating the political economy of the city.” (The “Mastodon” was not the gargantuan mill, but a reference to parts of a prehistoric skeleton found during its construction.) Evidently, New England did not have a monopoly on late-century textile production.

With this boomtown on the Hudson, a new field of migration opened for French Canadians facing adverse economic circumstances in Quebec. Sustained immigration to various parts of New York State was by then decades-old. French Canadians were an inescapable presence in Clinton County; they had a well-established institutional network in Plattsburgh. Some likely worked as laborers and tradesmen along the Erie Canal. Dr. E. B. O’Callaghan met a small group of men from Quebec travelling on the Hudson in 1846 or 1847; at that time, future Civil War hero Edmond Mallet was growing up in Oswego.

Cohoes was something new, in this state—and offered steep competition to the Fall Rivers and Manchesters of the world. From less than 10 percent in 1860, French Canadians quickly grew in numbers and amounted to a quarter of the city’s population by 1880. At this date, 1,100 French Canadians worked in Cohoes’ cotton sector. Most lived on “The Hill” (essentially, their “Little Canada,” though shared with the Irish) overlooking the mill facilities, by the Mohawk River. Cohoes rivaled New York City as the largest center of French-Canadian population in the state.

The rapid influx led to the creation of distinct religious and cultural institutions. The Roman Catholic bishop of Albany lent his blessing to the establishment, in 1868, of the national parish of St. Joseph. French Canadians had their own temperance society as well as a French-language newspaper; Misaël Authier founded La Patrie nouvelle in 1876 and it survived some fifteen years, unusual longevity for a nineteenth-century Franco-American publication.[1] The city sent delegations to state conventions of French Canadians and to larger regional events. It was in Cohoes in 1882, according to attorney Hugo Dubuque, that editor Ferdinand Gagnon delivered the finest speech of his distinguished oratorical career. Socially and culturally, Cohoes was closely connected to Montreal, its hinterland, as well as the great centers of the New England states.

If this story seems fairly typical, Walkowitz’s treatment of Franco-Irish relations deviates from inherited narratives about conflict in New England textile centers. Relations appear to have been far less contentious in Cohoes. For one thing, although operatives had to swallow a substantial wage cut, Harmony continued to operate through the depression of the 1870s, alleviating labor competition and limiting repatriation.

Some recent accounts state that the company recruited heavily in Quebec, which seems a likely scenario as prosperity returned at the end of the 1870s. We have at least one surviving report that suggests that Harmony continued to do so during a strike in 1880. But in Cohoes we have ample reason to believe that French-Canadian immigrants were quick to embrace what some scholars call “working-class Americanism.” They adjusted to and accepted labor activism, partnering with other ethnic groups to claim their rights not merely as Americans, but as American workers. It became increasingly difficult to invite Quebec workers to break strikes of French-Canadian operatives. A prolonged strike in the summer of 1882 revealed a united Franco-Irish front. Harmony began to recruit “knobsticks” in the most unexpected of places. It contracted with a steamship company to draw in Swedish replacement workers. The strike collapsed due to hunger—and to eviction notices served in company tenements apparently to make room for the Swedes. The type of unity and enthusiastic support for militant labor tactics seen in Cohoes would only surface on the same scale a generation later in more easterly cities.

Come back next week for Part II.

[1] Commercial competition emerged with Benjamin Lenthier’s creation of Le Drapeau national in nearby Glens Falls several years later. It was also the beginning of a partisan rivalry between the two publishers, Authier being Republican and Lenthier a committed Democrat.

My parents , Yves and Suzanne , moved here in 1954 so I can attest that it’s still happening.

My family moved from St Jean sur Richelieu to Whitehall, Ny. Then on to Cohoes in the next generation. I’m the family historian, I’d be happy to share my research

Hi Cindy, My family moved from St Jean sur Richelieu to Whitehall, NY about 1867 and a couple years later to Cohoes. The first was Moise/Moses Benjamin and his wife, Celine Masse. I’m Gloria Waldron Hukle. Author http://www.authorgloriawaldronhukle.net I’m working on my 6th book which follows the Benjamin and the LaCroix..

All of my great grandparents arrived in Cohoes between 1891 and 1901. Philomean Marcille Gaudette (widow of Joseph Franklin Gaudette) arrived in 1891 with her 4 grown children. Her parents and several of her siblings also emigrated to Cohoes at this time. She and 3 of her children worked in the Harmony Mills and all 5 lived in the Mill Housing at 15 Cataract Street.

My maternal Great Grandparents Philias and Vitaline Paquin Lanoue arrived in Cohoes in 1902 from Henryville Quebec. Philias worked in the Harmony Mills as a weaver. They settled into mill housing at 29 Mangam Street.

Both the Lanoue and Gaudette families were Acadian refugees from Port Royal, displaced in 1755 by Le Grand Dérangement,

Thank you for sharing your story, Jim. Love hearing these fascinating connections. Did you grow up in Cohoes, and was there still a thriving French community at that time?

Yes I was in Cohoes until I was 15 but never strayed too far away other than a few years in New Haven while working for GE.. I grew up “on the hill” my Gaudette grandparents lived on North Reservoir St. They had nine children and all of them grew up speaking both French and English.

My maternal grandparents one which was of French Canadian Decent spoke English, My grandfather was an infant when he came down from Canada but his parents spoke French at home.

The “hill at that time was a mixed bag of Irish, and French, with a few Polish families for good measure.

That’s great – such an interesting city. It deserves a lot more attention. Thanks again for sharing.

I was brought here to find out more information about my French Canadian decedents in the Albany area. This is opening up so much for me. Both of my fathers grandparents on both sides had an Irish mother and a French father. The French names were Deuel and Delisle I cant think of the Irish names but I will ask him. I dont know for fact that they were in Cohoe but its all lining up to seem that way. What beautiful thing.

Hi Zachary, thank you for sharing your story. The French-Canadian history of Albany, Cohoes, and Troy is little-known but there is a lot to it. Good luck in your research and don’t hesitate to reach out to again!

My Langlais family came about 1880 from Riviere du Loup, Quebec area, and My Soulier line about 1875 from Ste.Melanie, the Snay family from Vermont after coming in 1839 from near Beloeil, Quebec. Thanks all for sharing. Bill Simmons