See Part II here.

Like prior studies on this blog (here, here, and here), attention to Berlin highlights the extremely diverse experiences of French Canadians on U.S. soil. These “migrants on the margins” enrich the overall story of Franco-America. In Berlin’s case, this is especially true as we enter the 1930s. French Canadians were long reputed to be a conservative force among industrial workers of the U.S. Northeast. There is evidence from mid-sized manufacturing centers that the Irish and other laborers were successful in bringing French Canadians into a cohesive labor movement at the end of the nineteenth century. But their reputation lingered as, overall, they continued to eschew radical politics.

Depression-era Berlin offers a very different picture. When the city celebrated the centennial anniversary of its incorporation, in 1929, there was little to indicate that its steady growth would be checked. Only a few years later, the economic crisis had done just that. The International Paper Company shuttered its Berlin operation; the Brown Company, long the town’s engine of growth, eventually had to rely on municipal and State funds to continue its activities.

The Depression caused despair and dislocation across the country, some of which was felt in Berlin. That would have been enough to reinvigorate older radical politics. After all, there were precedents: the Knights of Labor had had “a large membership” in the city in the 1880s and Union-Labor and socialists groups had appeared in the early twentieth century. But it was something altogether different that led to activist, third-party politics in northern New Hampshire.

As historian Linda Upham-Bornstein explains, the city tax collector misappropriated $75,000 of municipal monies, which were lost in 1931 when his bank declared bankruptcy. To local citizens’ outrage, mayor Ovide Coulombe allowed the tax collector to remain in office despite the revelations; the council declined to pursue legal action. Some residents formed the Berlin Taxpayers Association and retained the services of attorney Arthur Bergeron, who petitioned the State to ensure the prosecution of the collector and the recovery of part of the funds.

Apparent corruption, the contempt of municipal elites towards the working class, and continued economic hardship produced another organization, the Coos County Workers Club. In early 1934, dissident groups coalesced as the Labor Party (which became the Farmer-Labor Party when it sought to broaden its base). It is telling of the situation in Berlin that this third party captured the mayoralty and three city council seats in March of that year. In 1935, it conquered half of the council seats, with Bergeron, the editor of the Coos Guardian, a labor paper, gaining the mayoralty. The party’s sights were already set on the State House. At the time, the Christian Science Monitor profiled two of its leaders:

Edward Lagassie [Legassie], a Farmer-Labor candidate for the State Senate, is a paper-mill worker and the father of our children. He denies his party is communistic, but he insists it is independent of Republican and Democratic forces. He and his party stand for more liberal workmen’s compensation laws, unemployment insurance and other direct benefits to the workers of the State.

Arthur J. Bergeron, graduate of Dartmouth and Harvard law school, helped organize the Farmer-Labor Party, and is its candidate for county solicitor. Leaders say the party has no official connection with the Farmer-Labor Party of the Midwest. A Farmer-Labor Governor of New Hampshire in 1936 is the party’s announced goal.

While the party’s program was very similar to the tenets of President Roosevelt’s Second New Deal, Legassie and Bergeron were disappointed with the National Recovery Administration and traditional politics.

By 1936, the party could boast 4,000 members, most of them in northern New Hampshire—and, according to the Monitor, mostly French Canadians. It hoped to capitalize on the industrial dislocation of Depression-era Manchester and grow its base in the southern half of the state. Its efforts in this direction were largely in vain, but it was a testament to the organization’s strength in Berlin that Republicans and Democrats joined hands under former mayor J. Alex Vaillancourt to try to defeat Farmer-Labor leaders. The latter had, after all, succeeded in implementing much of their municipal agenda while maintaining cordial relations with the Brown Company and protecting the city’s fiscal situation.

At the end of the 1930s, the Farmer-Labor Party was already past its prime, having outlived the burst of dissent that had created it, but Franco-American Amie Tondreau nevertheless ensured its hold on the Berlin mayoralty until 1943.

Throughout the middle part of the century, French Canadians retained their place of prominence in Berlin and Coos. In 1940, even after a decade of immigration restriction, more than 10 percent of Coos County residents were natives of French Canada. English Canadians were the next largest group of foreign-born white residents. In third place was a small group of some 205 people born in Russia or the U.S.S.R. Berlin was a microcosm of the county. There, after the Russians, were Norwegian- and Italian-born populations.

Following the trials of the Depression, Berlin experienced a late golden age that lasted into the 1960s. Afterwards, the mills changed hands a number of times, with short bursts of prosperity concealing the challenge of foreign competition and rising costs. Gradually, cuts were made. Canadian assets, including timberland and the pulp mill in La Tuque, were sold off. Plant closures in 2001 and 2006 definitively ended the era of large-scale manufacturing in northern New Hampshire. But that fate—the product of larger economic circumstances—cannot hide over a century’s worth of local accomplishments.

For instance, in the 1860s, Berlin welcomed Elmire Jolicoeur, a teacher and boardinghouse keeper who helped to attract her fellow Canadians to the town. She would later get credit as the inventor of French-Canadian casserole—dubiously, as it turns out. A generation later, local workers set the “best sawing record on a single-cut band saw in an eleven-hour shift,” as recognized by the American Lumberman. The city was the birthplace of both Earl Tupper (of Tupperware fame) and Canadian musicologist Gaston Allaire; it was also home to one of the tallest ski jumps at this end of the country. Next-door Gorham was home to the great Cascade plant, “the finest paper mill then in existence and the world’s largest self-contained unit making both raw pulp and finished paper.”

Berlin’s recent history is best told by those who experienced it and it just so happens that those voices are easily accessed. Anyone who is interested in learning about the North Country’s history should view At the River’s Edge: An Oral History of Berlin, New Hampshire, directed by Scott Strainge and released in 2010.

What of French-Canadian heritage through this period of transition? As researcher Eric Joly explained in 2001, in the last third of the century, in the wake of industrial woes, the city’s population declined by over 20 percent; French culture receded especially with the closure of bilingual Notre Dame High School in 1972. Just as Berlin’s Little Canada formed fairly late during the “great hemorrhage,” its French character survived longer than in many other places. “Outside of northern Maine,” Joly wrote, “Berlin is the city where we find the highest number of people claiming to speak French at home in New England.” Two-thirds of residents claimed French heritage by the late 1990s.

The author studied local youths’ attachment to their parents’ tongue and identity. He found the teenagers to be far less fluent in French than the older generation. But many nevertheless claimed French heritage—preferring the label of French-Canadian over that of Franco-American, actually. Without formal institutions devoted to the preservation of French, Joly concluded, “this Franco-American community is now experiencing its most critical period.” Perhaps its members may learn from the trials of other Franco communities in the U.S. Northeast—and find inspiration from the revival of French-Canadian culture in select cities, just as Berlin’s own history has inspired others to invest there.

Bibliographical Note

The Berlin and Coos County Historical Society is arguably the best resource for learning about the North Country—both in person and online. Its website holds historical images, portraits of different neighborhoods, and archival material, including digitized issues of the Brown Company’s Bulletin. Another website, a private initiative, also holds a wealth of information. The preservation of Berlin history is a great credit to the Historical Society (currently led by Renney Morneau) and to such active citizens as the late Paul “Poof” Tardiff. Two pictorial books have appeared—by Morneau and Jacklyn Nadeau—which commemorate the city’s better-known people and places.

Few scholarly articles have brought focused attention to Berlin’s history. Among those cited above are William G. Gove’s “New Hampshire’s Brown Company and Its World-Record Sawmill,” Journal of Forest History, 30.2 (1986); William L. Taylor’s “Documenting the History of an Industrial City: The Brown Company Photograph Collection of Berlin, New Hampshire,” IA: The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology, 19.1 (1993); Eric Joly’s “L’identité dans un milieu minoritaire: enquête auprès de la jeunesse franco-américaine de Berlin, au New Hampshire,” Francophonies d’Amérique, 12 (2001); and Linda Upham-Bornstein’s “Citizens with a ‘Just Cause’: The New Hampshire Farmer-Labor Party in Depression-era Berlin,” Historical New Hampshire, 62.2 (2008). See also Rebecca Rule’s article, “A Brief History of the Brown Paper Company,” cited above, in Northern Woodlands; on French Canadians in the American lumber industry, Jason L. Newton, “‘These French Canadian of the Woods are Half-Wild Folk’: Wilderness, Whiteness, and Work in North America, 1840–1955,” Labour/Le Travail, 77 (2016). Studies on mortality among pulp and paper workers appeared in 1979 and 1989 in the British Journal of Industrial Medicine.

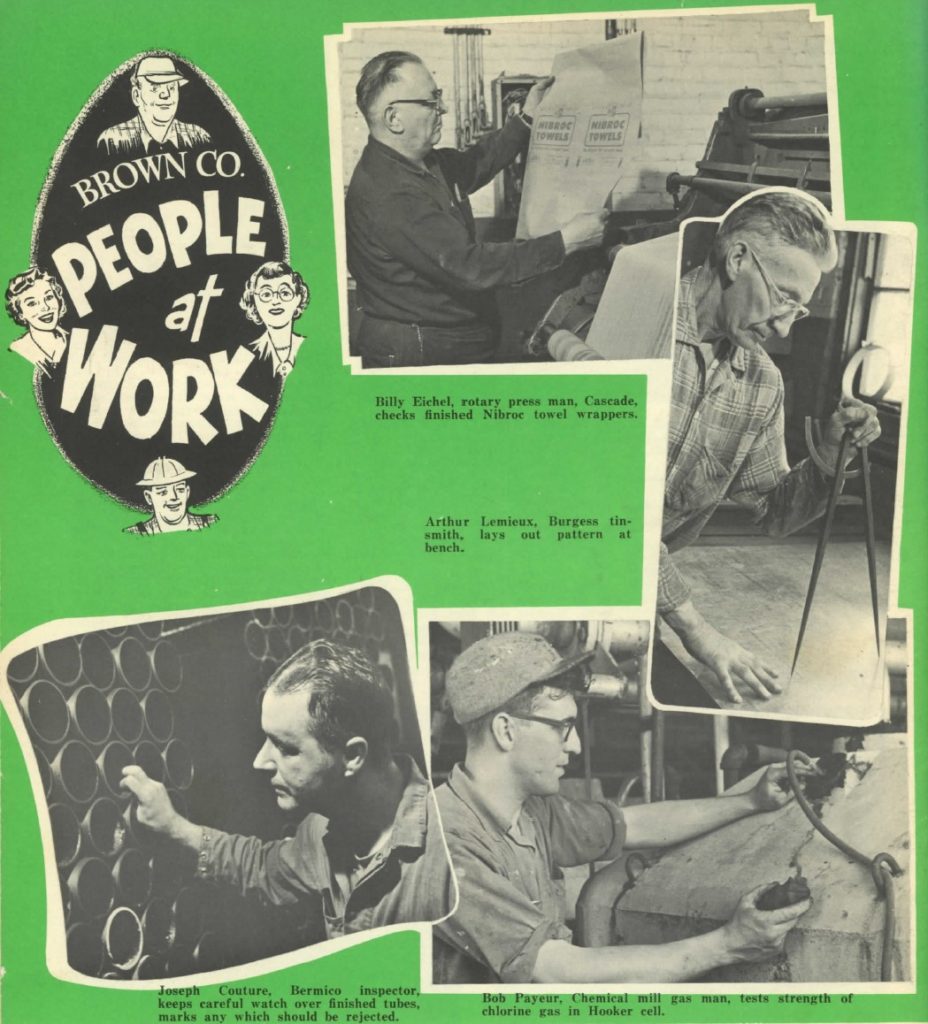

Images from the Brown Company’s archives have been digitized by Plymouth State University.

Older works on the history of Berlin and Coos County are available on Archive.org and Google Books. Many annual city reports may also be accessed on Archive.org.

Additional information for this series on Berlin was drawn from contemporary newspaper reports and U.S. Census returns.

Leave a Reply