The story of the French-Canadian diaspora that began in the nineteenth century is perhaps not as well-known now as it should be. Yet some aspects of Canada’s emigration history are even more obscure. One easily overlooks the fact that English Canada experienced a comparable exodus from the 1850s to the 1920s. Nova Scotia was particularly hard-hit. What began as a seasonal movement of young people—to work as farm laborers in Maine or as crewmen on Massachusetts ships—eventually led to the permanent settlement of kinship groups in the U.S. Northeast, as had happened with French Canadians leaving rural Quebec.

When we realize that French Canadians were not exceptional in leaving the “homeland,” we come to see a larger Canadian story that points to structural problems—and casts those who held the reins of the country in a particularly unfavorable light.

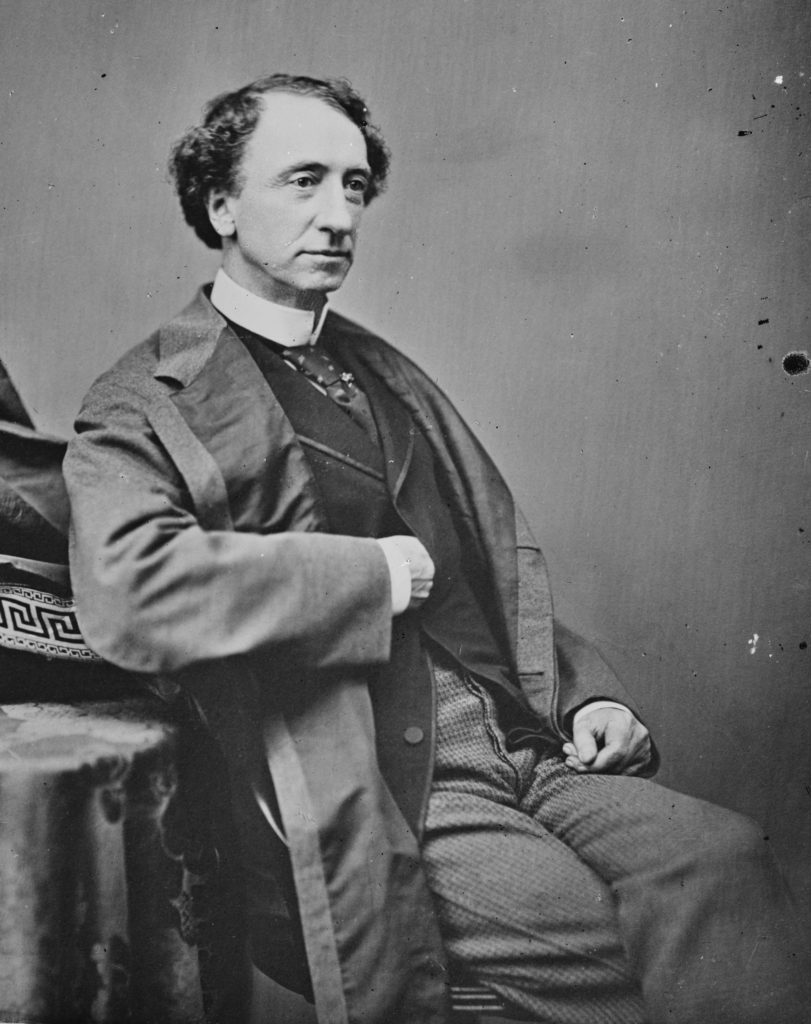

As with other regions of British America, Nova Scotia lost markets with the abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty, a limited free-trade agreement between the colonies and the United States, in 1866. Agriculture and the fisheries felt the shock. At the same time, shipping and shipbuilding suffered from the rise of steam power and iron-hulled vessels. The high-tariff economic policy implemented by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald at the end of the 1870s helped certain areas of the province industrialize, but those benefits were felt quite unevenly. And then there was the lure of higher wages south of the border—and the lure of a more cosmopolitan life that contrasted sharply with the social world of the Nova Scotian countryside.

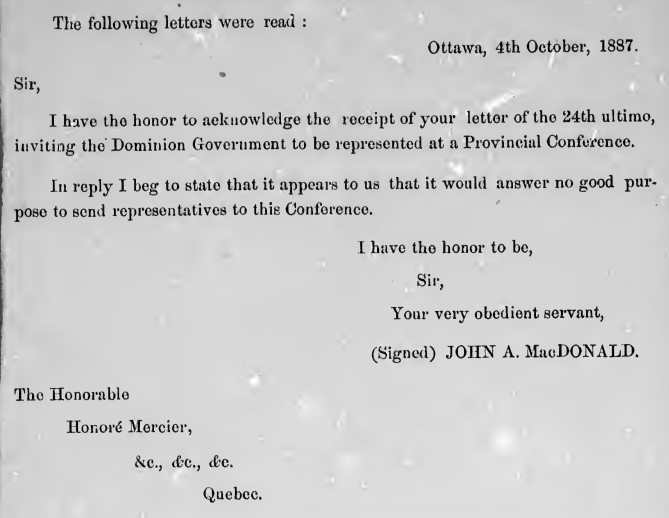

As I have written elsewhere, by the 1880s, there was a widespread sense that Canada was a sick country. (Prosper Bender made that plain time and again.) More and more residents looked south for salvation of a kind. In Nova Scotia, many political leaders and newspaper outlets envisioned a return to economic reciprocity as the only solution. But the absence of sustained economic gains under the Macdonald government also opened upon more radical paths. In 1886, long before Quebec had a cohesive sovereignty movement, the Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia passed “repeal resolutions”: it would seek to leave Confederation and consider the establishment of a distinct Maritime Union that could pursue its own economic and commercial interests. Provincial Premier William Fielding stepped back from this ambitious project the following year. Yet, when combined with the recent North-West Rebellion or Resistance and the formation of the Parti national in Quebec, the Repeal Movement seemed to say a great deal about the state of the Dominion.

At a time when there were few standard, trustworthy measures of economic activity, emigration became exhibit A. Census returns, passenger manifestos, and public accounts all attested to depopulation—and thus to something terribly wrong in the Dominion of Canada.

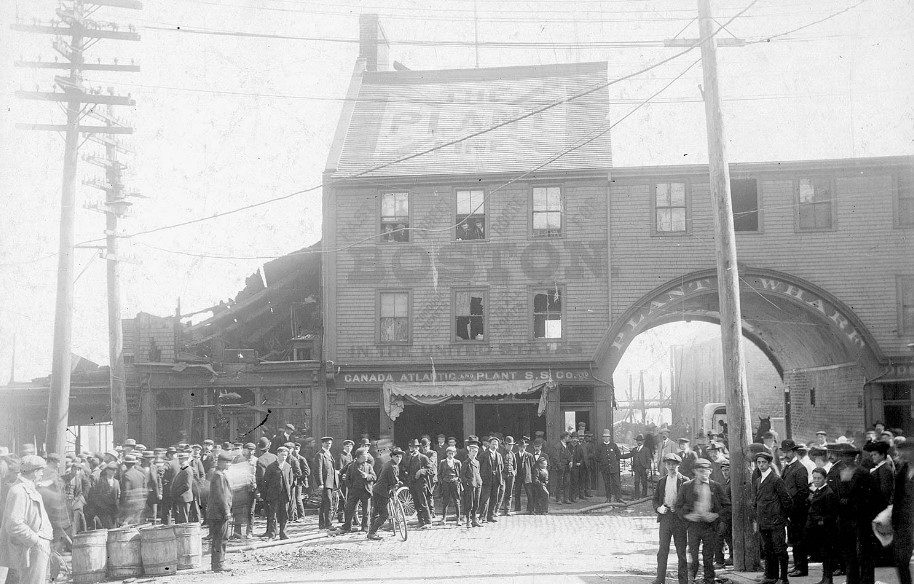

In the 1880s, a Maritimer could join the Intercolonial Railway at any point and be in Saint John, New Brunswick the next day at the latest; they could then board a steamer and be in Boston the following morning. The International Steamship Company started opening its direct line earlier in the season to accommodate that Nova Scotian “exodus.” The opportunities and the ease of transportation fueled the migration, such that the province’s population only grew by 2 percent in the course of the 1880s. Its share of the country’s population declined quickly and so did its political influence. The expatriates formed a distinct community in Massachusetts, but they were to be found elsewhere. In 1910, English Canadians—a majority coming from the Maritimes—constituted the largest minority group in Maine (exceeding the next most important group, the French Canadians).

Whereas we might expect the tone of American newspapers to be triumphant—the magnetic power of the U.S. economy confirming its natural grandeur and equally great destiny—in some cases writers and editors were frankly puzzled. In 1869, a Manchester, Vermont, outlet explained,

we regard [Canadian emigration] as one of the strongest and one of the most anomalous [movements] of the time, unless political and religious motives profoundly influence it, for the country these people leave is mildly governed; not more taxed than our own; protected and fostered by the mother country; possessing magnificent lakes, rivers, savannahs, and forests of fine timber, and teeming with agricultural and mineral wealth, if properly developed.[1]

The article seemed to suggest that “[d]islike to the government” and “the hope of a better social condition” accounted ultimately for this widespread movement. But the author was overlooking the struggles faced by certain sectors following the end of Reciprocity, and the caveat “if properly developed” pointed to economic activity that was still on a far-away horizon. Nor could the industrial advances of the two countries be meaningfully compared at that point. Six years later, the Portland, Maine, Daily Press also commented on the natural wealth of Nova Scotia; that emigration nonetheless persisted “indicate[d] a radical mistake in its political economy.” The quest for reciprocity simply hinted to the likely benefits of annexation by the United States.

In fact, in the late nineteenth century, Canadian policymakers sought continually to harness the economic vigor of the United States to their own ends. Only when the possibility of free trade fell through did John A. Macdonald choose the alternative path of replicating American policy and gambling on high tariffs. Some areas of Nova Scotia did experience industrial growth in the 1880s, but in the longer term the National Policy simply placed the economic fate of the Maritimes in Central Canada’s hands.

In Quebec, elites’ preferred panacea was domestic colonization (discussed here and here). In other words, if better roads into the wilds of Quebec were built, and good lands put up for sale, “no true Frenchman” would dare to leave the country; families would eagerly seize the opportunity to remain at home, in agriculture.

The story in Nova Scotia was different. Newspapers—the natural conduit between policymakers and the people—evinced a kind of defeatism. Outside of free trade, editors relied on sentimental appeals to youths. In the late 1870s, the Bridgetown Weekly Monitor printed pieces titled “Family Grave-Yards” and “The Homestead” that emphasized filial duty—the duty to remain, really. But truly there were very few concrete policy proposals. Elites were more focused on drawing immigrants from abroad to replace those people leaving the province than on retention per se. It is as though nothing could be done.

Heavy emigration to the United States from all parts of Canada points, if not to significant structural issues north of the border, then at least to sizeable disparities between the two countries in the late nineteenth century. In regard to research, the next step is to determine the extent to which this owed to policy failures—if indeed something could be done. In recent years, John A. Macdonald has been criticized for his view of and policies towards Indigenous peoples. Was his economic vision also misguided? What about provincial leaders in Quebec and Nova Scotia? Did they simply lack the policy levers that might stanch the flow of people across the border? A deep dive into the era’s political responses is in order.

For those planning to undertake primary-source research on the topic, Canadiana and its sizeable database of late nineteenth-century newspapers is an excellent starting point. I also recommend the keyword-searchable collections of BAnQ and the Library of Congress. Alan Brookes is the best-known authority on emigration from the Maritimes; his M.A. thesis and Ph.D. dissertation were never published, but his insights do appear in articles published in Acadiensis. For additional information on domestic colonization and repatriation in Quebec, see Jack Little’s classic study on the topic.

I will be presenting my findings on this issue on October 21 as part of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society lecture series. More information to come.

[1] As Sean Kheraj explains, the natural bounty of British North America was in fact central to the political project put forth by the Fathers of Confederation.

Pingback: This week’s crème de la crème — August 29, 2020 | Genealogy à la carte

Pingback: This week’s crème de la crème — September 19, 2020 | Genealogy à la carte