This week the blog takes a slightly different tack to recognize landmark anniversaries that had bearing on the history of French Canadians.

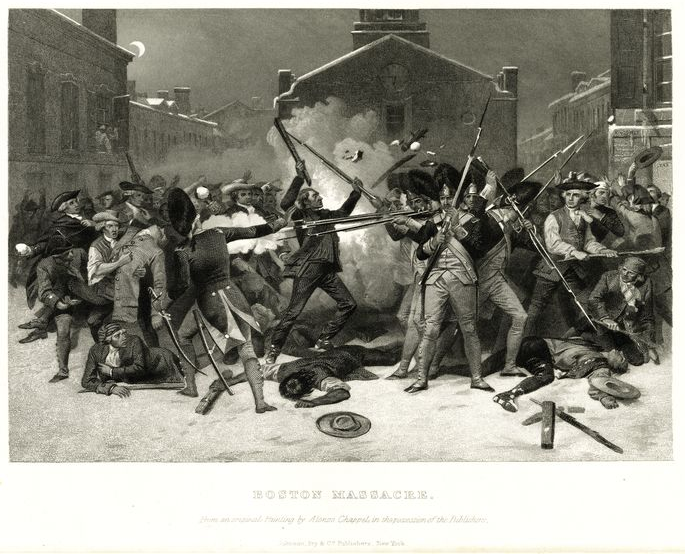

The first of these comes a week from today. On March 5, 1770, a scuffle in the snow led British regulars billeted in Boston to open fire on civilians. Within minutes, three colonists lay dead; others would die shortly after. No, none of them were Canadian. But we might argue that this event, enlarged by the American radical press, contributed as much as any other to the sense of siege that inhabited New England on the eve of the Revolution. The “massacre” fed into a narrative about the threat of standing armies and the oppressive designs of authorities in London. It also contributed to paranoia—and without that paranoia, there is really no understanding the Patriot invasion of Quebec in 1775.

The connection may seem tenuous, but the apparent willingness to use force of arms against civilians was still fresh in colonists’ minds in the spring and summer of 1775. The fates of New England and the Province of Quebec were further enmeshed with the “Intolerable Acts” of 1774, which closed the port of Boston as well as showering the Canadiens with goodies. Quebec might prove to be the springboard for the utter subjugation of the Thirteen Colonies. The psychological climate developed through the Boston Massacre justified, ultimately, the Continentals’ willingness to go on the offensive.

The failed occupation of Quebec would create the separate national paths that are still with us today—paths nevertheless blurred by the “invasion” of the U.S. by French Canadians particularly after 1840.

The other anniversary is Maine’s bicentennial. On March 15, 1820, Maine officially split from Massachusetts and joined the Union. Canadians had nothing to do with the making of this new state, but in time immigrants from Quebec would come to experience its effects first-hand. Had Massachusetts kept its northern bastion, immigrants in Maine would have been connected to a larger pool of potential allies with whom they might have effected decisive change at the state level. The Bay State, after all, came to hold 40 to 50 percent of Franco-Americans in New England as well as having other large Catholic and non-Yankee populations. The French-Canadian group in Maine, by contrast, was something of a political orphan and would feel the full force of restrictive legislation starting in the 1890s.

Evidently there is no disentangling the history of French Canada and that of the United States—which intersect in often surprising ways.

For more information on the first anniversary, please consult my series on anti-Catholicism during the Revolution and my work on the Quebec invasion and its consequences. I am also happy to provide more extensive pieces that have appeared in academic journals. I have written about the “Massachusetts divorce” in the Lewiston Sun Journal.

Next week: The women of the Franco-American press.

Leave a Reply