Part II: The Quebec Act

See Part I here.

Whenever Catholics were politically disarmed, their place in majority British societies involved numerous inconsistencies. More immediately threatened and theologically justified than subjects in Britain, New England’s Puritans also harboured far stronger anti-Catholic feelings than other colonists. Congregationalist ministers identified the Catholic Church as the Antichrist as the French and Indian War began and as New England troops prepared to take Acadia, where bigotry legitimized various depredations. The ultimate outcome, expulsion, was practicable in those territories. As British forces won the surrender of New France in 1760, however, colonial authorities had to contend with, and adjust to, a population overwhelmingly French and Catholic which would not be displaced – only, perhaps and over time, assimilated. In a series of small precedents to the Quebec Act, Governor James Murray expanded traditional British liberties to gain the support of the clergy and ensure Canadian loyalty. Though they suffered some civil and religious disabilities, the French of the St. Lawrence valley were spared the Acadians’ fate.[1]

According to Jefferson, the Quebec Act of 1774 replaced the open and fair English legal system set forth in Britain’s Constitution with an arbitrary administration. In what appeared to be the British Ministry’s designs for the entire continent, Quebec was now in the hands of a governor, unchecked by an elected assembly, and the Catholic Church. The recognition of the latter was the main problem for opponents. The Act stipulated that Canadians might now freely practice “the Religion of the Church of Rome” and that their clergy could “enjoy their accustomed Dues and Rights,” so long as this did not prove injurious to Protestants. The re-establishment of French civil law further threatened the Thirteen Colonies’ interests with the extension of Quebec’s boundaries into territories claimed by Pennsylvania and Virginia.[2]

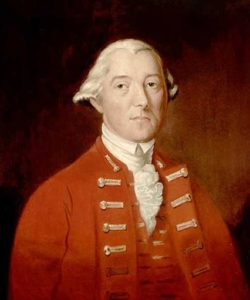

The Quebec Act was more than an act of statesmanship and much less than the reflection of Enlightenment feelings in Britain. The Act was the product of lobbying in London by Governor Guy Carleton, Murray’s successor. Murray had distanced himself from Quebec’s “British Party,” marked by zealous anti-French and anti-Catholic feelings. Seeking to strengthen colonial power, Carleton went further. Late in 1773, he could argue that a quick resolution to the challenges of governance in Canada would enable the men of Westminster to devote greater attention to the crisis in the Thirteen Colonies. And, to echo the cynical view of Michel Brunet, the ambitious Carleton would emerge aggrandized from the reaffirmation and the geographical expansion of his authority. This meant alienating the British of Quebec, who deplored the absence of representative institutions, the endorsement of “papistry,” and the formation of an aristocratic pact sealed by Carleton and Canadian allies against their mercantile interests.[3]

American colonists, for their part, felt besieged. A single stroke of the King’s pen seemed to negate their struggles through the French and Indian War. With the return of “ecclesiastical and civil tyranny,” Congregationalists altered their language: the Antichrist was not merely Rome, but any power that violated Christian freedom and compacts between subjects and their government. More secular figures no less saw the imminent introduction of despotic rule. To Alexander Hamilton, the Act established a “Nation of Papists and Slaves”; truly it was an “instrument” for “the subjugation of the colonies, and afterward that of Great Britain itself.” Yet, if anger greeted the news of the Act in the Thirteen Colonies, George III was not ascribed conspiratorial designs. The language of the Continental Congress, which assembled shortly thereafter, was quite moderate. In its first session, Congress did not question the King’s authority or character. This is consistent with Brendan McConville’s depiction of a “royal America,” a fiercely proud bastion of Anglo-Saxon Protestantism whose colonists “expressed an intense admiration for the monarchy.” The King came to be the sole connection between metropole and colonies, to whose benevolence provincials might always return. It is in this context of political dispute and intense royalism that the sovereign’s image underwent a major transformation.[4]

The American press tied the Act to Tory ideas and challenged the “forwardness of the present Ministry.” To one observer, the Quebec Act was “of the same stamp, as if [the minister] had advised his Majesty to introduce an army of foreign soldiers into the nation, in order to tyrannize over and enslave his people.” “The Bill is indeed,” a Boston outlet noted, “High Treason against the Constitution of England; and if the Minister be not impeached . . . there can be no spirit or virtue in the nation.” It further appeared that “the friends of the abdicated Family now hold the reins of power.” The upper house, too, was indicted, as a Philadelphia sheet asked, “[w]here were my Lords the Bishops?” In other words, far from the King being part of a popish plot, the assault on the Protestant establishment had Carleton, Prime Minister Lord North, and a corrupt Parliament as its architects. Through 1774, George III remained a father to his American people. Redress, if unlikely through Parliament, was still possible through him.[5]

Congress’s expressions of hope contained internal contradictions destined to collapse. In their condemnations of Parliament and North, the colonists ignored their ruler’s position as king-in-Parliament, at whose pleasure the government served. George III was the apex of both the legislative and executive branches who, when signing the bill, declared that the bill would resolve problems of governance in Quebec and, “I doubt not, have the best effects in quieting the minds and promoting the happiness of my Canadian subjects.” In London, people gathered to the cry of “No Popery, no French government.” The sovereign had compromised himself as head of the Church of England and defender of the Protestant faith. The colonists, still, continued to lament the influence of “designing and dangerous men” over the King, appealing to him directly as in times past. As no redress came, the contradiction was exploded: the King had facilitated this breach of the Constitution and should suffer the consequences, if only in the colonies.[6]

To be continued.

In the next installment: From Redress to Revolution

[1] John Mack Faragher, A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland (New York City: W. W. Norton and Co., 2005), 225, 286, 300-1, 352, 437-38, 445-46.

[2] Sir Reginald Coupland, The Quebec Act: A Study in Statesmanship (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968), 208-17; General Congress of the United States of America, Declaration of Independence (1776), in Essential Documents.

[3] Michel Brunet, Les Canadiens après la Conquête: De la Révolution canadienne à la Révolution américaine (Montreal: Fides, 1969), 142-43, 211-12, 223-26, 251-53, 261-63, 268, 291. See also Paul David Nelson, General Sir Guy Carleton, Lord Dorchester: Soldier-Statesman of Early British Canada (Cranbury: Associated University Presses, 2000).

[4] Nathan O. Hatch, The Sacred Cause of Liberty: Republican Thought and the Millennium in Revolutionary New England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 17, 38-44, 52, 73, 86-87; Bonomi, Cope of Heaven, 216; George F. G. Stanley, Canada Invaded 1775-1776 (Toronto: A. M. Hakkert, 1973), 16; Brendan McConville, The King’s Three Faces: The Rise and Fall of Royal America, 1688-1776 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 7-8, 49-80, 251, 290. See also Eric Nelson, The Royalist Revolution: Monarchy and the American Founding (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2014).

[5] Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet 3, no. 149 (29 August 1774): 2; “Epigram,” The Essex Gazette 7, no. 320 (6 September 1774): 1; Boston Post Boy, no. 890 (5 September 1774): 2, all in Archive of Americana, America’s Historical Newspapers (Series 1-3).

[6] “London,” Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, no. 71 (25 August1774): 2, in Historical Newspapers; “Petition of Congress to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty [26 October 1774],” Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789: Vol. I. 1774, ed. by Worthington Chauncey Ford (New York City: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1968), 118.

Leave a Reply