Gentlemen: I thank you most kindly for this hearty British reception, which I take as a manifestation of your sympathy and good-will for one in misfortune. It bespeaks the true instincts of your race. I trust you may ever remain as free a people as you now are, and that under the union of your provinces you will grow great and prosperous as you are free. I hope that you will hold fast to your British principles, and that you may ever strive to cultivate a close and affectionate connection with the mother country. Gentlemen, again I thank you.

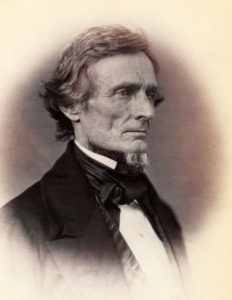

– Jefferson Davis, Sherbrooke, 1867

Ulysses S. Grant was not the only eminent American visitor to Canada in the aftermath of the U.S. Civil War. While Grant visited Lincoln’s tomb in Springfield, Illinois, in 1865, a Quebec paper reported that Jefferson Davis, Jr., son of the former Confederate president, had matriculated at Bishop’s College School in Lennoxville. According to Le Courrier du Canada, a daughter was already enrolled at the Couvent du Sacré-Coeur at Sault-au-Récollet, outside of Montreal. The elder Davis followed several years later.

The defeat of the main body of Confederate forces at the end of the war forced Davis and other officials to flee Virginia. Davis himself was captured in May, a full month after Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Grant. He would be held as a prisoner at Fortress Monroe for two years—that is, until he was turned over to civil authorities and released on bail in May 1867. The Journal de Québec reported on the “great act of justice and humanity” that was his release and announced Davis’s imminent arrival in Montreal.

On both sides of the border, the press regularly depicted Davis as a martyr. Still, hostile feelings persisted in the Northern states, such that the ex-Confederate leader travelled to New York City upon being released, and from there, discreetly, to Montreal. His wife, Varina, followed soon after with two African-American servants.

In Montreal, Davis initially kept a low profile, which was no small task. At the end of May, when he visited Toronto, 2,000 people turned out to the docks to welcome him. Reports suggest that the cheers that greeted him in various locations far exceeded those extended to Grant in 1865. Davis went on to Niagara Falls, and on June 4 gave away the bride—a Southerner—at a wedding in Toronto.

It was about four weeks later that Davis went to Lennoxville, near Sherbrooke, to visit Jefferson Jr. According to a London, Ontario, newspaper, Davis “was received at the Sherbrooke Railway Station by a large crowd of people, who cheered him heartily when the train arrived. Several persons entered the car to explain to him the object of the cheering, when Mr. Davis presented himself on the platform and was received with another round of cheering.”

To this “hearty British reception” he responded in the above-quoted terms. The paper did not specify the date of Davis’s arrival in Quebec’s Eastern Townships, but it was evidently very close to July 1, when the British North America Act took effect. There is no small irony in that the U.S. Civil War helped to give the Confederation project the necessary momentum. But Britain and its colonists had extended remarkable sympathy to the seceding states and Davis now spoke in a similar spirit of friendship.

Following his remarks, Davis “retired within the car. Three cheers more and one for Mrs. Davis were then given, and the cars moved away toward Lennoxville, where he and his family alighted and were again the recipients of a hearty reception from the crowd awaiting him.”

Davis was celebrated in Montreal through the summer; in early August, he explored northern Vermont. It was in Lennoxville, however, that he would spend much of 1867-1868. There, he and his family lodged at the British-American Hotel. The “Jeff Davis House” that still stands in Lennoxville was actually the home of the Cummins family, whom the Davises regularly visited. In the small Townships community, the former president proved a quiet and reticent figure. The peace of mind he sought was not assured, however. He was in poor health; he felt the defiance of Northern sympathizers, who occasionally made life difficult for his son.

Then there was the impending trial, for which he twice went to Richmond, Virginia, and both times found the proceedings postponed. In early 1868, the family visited their old plantation in Mississippi and found it in ruins. Davis passed through New York again—this time with his wife and one African-American servant—in late March on his way to Montreal.

Davis’s financial situation did not improve in Canada. His time in the northern dominion ended in July 1868, when he travelled to England in pursuit of business opportunities. He did not stop there, however, nor did he confine himself to lucrative activities. In January 1869 he was in Napoleon III’s France. He notably visited the military academy at Saint-Cyr with John Slidell, one of the Confederate diplomats seized from the Trent by the U.S. Navy in 1861. From Europe, where he was held in high regard, Davis returned, at last, in the fall of 1869, disembarking in Baltimore.

By then, the nightmare of the prospective trial was over. On Christmas Day, 1868—a month after Grant’s election to the presidency—Andrew Johnson had issued a general pardon to all those having taken part in the “Rebellion.”

In Davis’s case, the pardon reflected the state of public opinion in the United States as well as in Canada and Europe. Press reports had already consecrated him as a gentleman, principled, stoic, and honourable. It was a sign of larger things to come in the 1870s and 1880s that public figures and the press seldom discussed the cause that had justified secession, or the horrors of human bondage in the Southern states. There was little evidence that he was tainted by this cause, and its ultimate defeat seemed only to aggrandize him.

That Davis earned Canadians’ admiration on a scale Grant did not experience in his own time in Canada may be attributed to the threat posed by the Union and a long series of wartime controversies. Yet it may also be that British North Americans followed millions of American citizens in turning a blind eye to the problem of slavery, out of wilful ignorance as well as racial prejudice.

While I leave it to others to debate the recognition of Jefferson Davis’s time in Canada, it is evident that with appropriate context, it may help us shed light on the less commendable chapters of our history and their legacy.

Sources

George E. Carter, “A Note on Jefferson Davis in Canada – His Stay in Lennoxville, Quebec,” Journal of Mississippi History, vol. 33, no. 2 (1971), 133-139.

- Carter cites Bertha Weston Price, “Old Records Reveal Account of Stay in Lennoxville of Jefferson Davis, Confederate Leader, and His Family,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, February 24, 1940, and Fred Kaufman, “Jefferson Davis at Lennoxville,” Sherbrooke Daily Record, January 9, 1946. Both of these articles must be approached critically, as they are based to a great extent on reminiscences long after the fact of Davis’s visit. There are, in addition, issues with Carter’s references and chronology.

Rice University’s portal on The Papers of Jefferson Davis includes a chronology of his postwar life.

Newspapers:

- Le Courrier du Canada, September 22, 1865; May 27, 1867; February 12 and December 21, 1868; February 10 and October 18, 1869

- Le Journal de Québec, May 17, June 13, and August 13, 1867; April 2, 1868

- Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Advertiser, May 31, June 5, and June 15, 1867

- New York Times, July 7, 1867

Leave a Reply