Please indulge my truisms for a moment—and entertain a post which, in true scholarly spirit, offers more questions than answers.

To say that the Great Republic is a big country—physically—usually means something very abstract, except for those of us who have a habit of driving when air travel is available. My better half and I did just that last month to vacation and to visit her family in Mississippi. I was reminded—as I realized years ago when crossing the country by train—of the sheer size of the United States, something easily lost on New Englanders as well as frequent fliers.

In the last two centuries, new means of transportation and communication have helped to collapse distances and to conceal our collective relationship with the land. Canals, steam power on water and land, automobiles, and especially air travel have produced noticeable detachment (literal and figurative) from the land. From horseback courier to telegraphy, from telephone to the happily obsolete fax machine and at last to the internet, the world has also grown smaller through the increasing instantaneousness of communication. At any given moment you can know in real time what is happening in Omaha, Nebraska, should you have such a troubling interest.

Of course, the world is not actually smaller and I am glad that we can still appreciate distances for what they are—and what they were to our forebears with few of our modern luxuries. It is a little harder to understand the discomforts they faced, though, even with the most candid travel journals. Historians are often of little help. We—yes, I plead some guilt here—are typically more interested in the conditions of both the place of origin and the destination, with little description of the actual conquest of distance. An optimist, I generally avoid quoting Thomas Hobbes, but certainly travel could often be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish,” and long. I encourage folks with an interest in traditional means of travel to watch The Home Road and read Bill Bryson’s Walk in the Woods and Rinker Buck’s Oregon Trail. As a preview, consider that it takes six months for a healthy, able-bodied, and determined individual to walk from Georgia to Maine; it often took as much time to travel from St. Louis to California on a mule-drawn wagon.

So what does this have to do with Franco-American history?

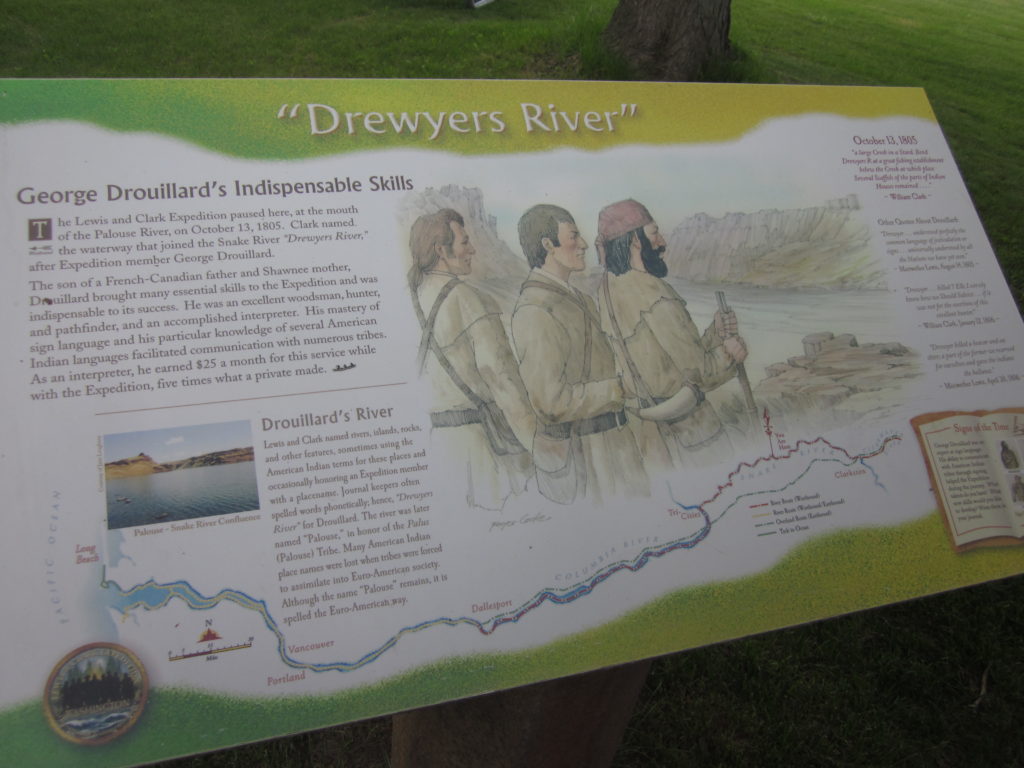

We can start with a longstanding depiction of French North Americans as explorers, adventurers, fur trappers and traders, travellers—eager and restless colonizers. Such representations are less common now, thanks to much-needed debunking. We must nevertheless account for the great arc of colonial settlement from the Gulf of the St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico. We must consider the growing basin of French settlement in the Detroit River region and along the Mississippi… and the voyageurs who accompanied messieurs Lewis and Clark at the dawn of the nineteenth century. We might also think of the French Canadians who settled in New York and New England prior to the completion of a cross-border railway in 1853. Or yet the occasional French Canadian and Franco-American who have the great idea of driving to Mississippi in June.

This is meant as a long-winded invitation to researchers to better assess the experience of travel among French Canadians and Acadians. What means were available to them and at what cost? What were the eye-opening moments and the discomforts? How did intercultural encounters occur along the way? How did various means of transportation compare with one another? How was knowledge about opportunities and destinations shared in places of origin and on the road? What were the prospects of remigration? What part did epistolary correspondence play in communication networks? (I wasn’t kidding about the questions.)

The other big question that arises from the meeting of geography and migration concerns colonialism. As much as some might want to think of French Canadians as practical vagabonds (a view especially prevalent in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century United States), the marks of their settlements, of the roots they planted all across North America are still visible, even with the inexorable march of acculturation. They colonized—even in the urban landscapes of New York and New England—and folded their expansion into an ideological system driven by faith and fear of cultural loss.

From this angle, we can wonder how and when French colonialism ends in North America. Is it fair to suggest that it ends in 1760, or in 1803? Can we meaningfully separate the goals and actions of state power from the initiative of individuals settling and utilizing the land? What of efforts made by the Roman Catholic Church and the government of Quebec to promote domestic colonization—or the semi-colonial Refugee Tract in upstate New York? What of the providential language surrounding the “colonies” (i.e. the Little Canadas) of the U.S. Northeast in the second half of the nineteenth century? That, of course, involved the reproduction of ways of life until then known along the St. Lawrence River—often from both a top-down and bottom-up perspective.

These are big questions that anticipate a great deal of debate among researchers. I would not expect easy answers. At this point, they simply suggest that there remains much to explore, uncover, and ponder in Franco-American history, not least in regard to space. This blog will continue to add to that conversation.

As always, comments are welcome below. Feel free, especially, to recommend readings that might benefit fellow readers of the blog.

Blog posts will appear here throughout the summer, with subjects spanning from New Hampshire to California, from the 1840s to the 1930s. In the meantime, I invite you to check out my piece at the History News Network on John F. Kennedy’s primary campaign in New Hampshire. As the names in the article suggest, Franco-Americans were part and parcel of his eventual success in the state.

Leave a Reply