As many of you know, I will be teaching a course on Acadian history this fall. In the process of building the curriculum, I have been discovering an immense amount of trustworthy educational resources online. Although this blog focuses primarily on the French-Canadian diaspora, Acadians merit considerable attention in the larger story of transnational North American francophonies. Below are links that may provide a very small introduction to that story. Please feel free to share other relevant sites or resources in the comment box.

More on Nova Scotia next week. As always, stay tuned!

Colonial history

Colonial Acadian history does not receive the attention it deserves. It is perpetually in the shadow of developments in the St. Lawrence River valley and in the Thirteen Colonies, where the colonial drama seems to be really playing out. Little of the scholarly conversation and few primary documents appear online—though Nicolas Denys’s account is well worth the read. Instead, I am sharing what amounts to a basic intro that will seem like well-worn territory for some readers, but a valuable start on the subject to others. Here we find the broad outline of the colony’s establishment and its eighteenth-century struggles.

It is worth remembering that the Acadia of the early 1700s bears almost no resemblance to the Acadia of the mid-nineteenth century. The ordeal of the 1750s and repatriation translated into different institutions, different areas of settlement, and different reconstituted families and communities. And, as always, we can afford to be skeptical of the seductive, romantic “golden age” narratives.

The Expulsion of 1758

On-line resources about the Deportation of the 1750s are numerous, so I will highlight one key resource which, though tackling an important aspect of the dispersal, could be easily overlooked.

New Brunswick has a large Acadian population to this day; Nova Scotia has Evangeline. Often left out of any discussion of Acadian history is Prince Edward Island, or Isle Saint-Jean as it was known during the French colonial period. Well, the island did have its share of French settlers and they too faced deportation. This website is an impressive collaborative project that provides valuable context about life on Isle Saint-Jean and what exile meant for the settlers—the stories of five French families help to illustrate that in a meaningful, personal way. The maps that trace these families’ journeys are a wonderful touch.

Acadian Migrations

To belabor the point just slightly, in the great realm of Canadian history, the story of the Acadian deportation is well-known. That this tragic saga has earned a Heritage Minute suggests that it is now part of the canon of Canada’s national narrative.

That it is well-known—beyond exceptional families whose oral tradition has preserved the memory of the expulsion—owes notably to the work of scholars who have dug into extant sources dating from the eighteenth century. While local communities supported museums, placed historical plaques, and preserved or revived cultural traditions, researchers have delved into the events and helped us appreciate the causes, trials, and legacies of the deportation. One of the most important pieces in this process of historical inquiry is Robert LeBlanc’s contribution to the Cahiers de géographie du Québec. LeBlanc was a long-time professor in the Department of Geography at the University of New Hampshire. His life was abruptly ended on September 11, 2001, but his immense contribution to Acadian and Franco-American studies is still very much with us.

LeBlanc’s piece in the CGQ traces Acadian migrations from the 1750s to the end of the eighteenth century. It has the great virtue (as with the author’s body of work in general) of being very accessible—with maps that are invaluable in understanding the new directions taken by Acadian society as it slowly recovered from the shock and trauma of dispersal.

The Wilderness Years

The period from 1763 to 1867 may well be considered the Dark Ages of Acadia. It’s not merely that Acadians in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia had lost distinct French institutions, struggled to rebuild, or faced daunting economic circumstances. That era is “dark” in great part because, from a historical perspective, we have very little first-hand documentation from which to reconstruct Acadian history in British America. But we do have instances of prominent individuals playing a leadership role within their communities, men who left their names to posterity, for instance the priest Jean-Mandé Sigogne and public official Amable Doucet. Doucet’s name has recently appeared in local news stories as a slaveowner, adding an interesting layer of complexity to our understanding of intercultural relations and economic stratification in early Nova Scotia.

The Dictionary of Canadian Biography is also a great point of entry when exploring the big names of more recent Maritime history—though we still await an entry for Pascal Poirier, a long-time “national” leader and the first Acadian senator.

The Acadian Renaissance

In the last third of the nineteenth century, the Acadians of Eastern Canada underwent what is commonly called a renaissance: a new sense of collective self developed through a distinct French-language press, the rise of new educational institutions, and semi-regular “national” conventions. Denis Bourque and Chantal Richard have done the historical community an immense service by collecting (often from disparate and obscure sources) the proceedings of these congresses. Their research has so far covered the earliest congresses, from 1881 to 1890, and then a second set, held from 1900 to 1908.

In this shorter piece, Bourque provides the context for and manifestations of this Acadian Renaissance. Perhaps the most fascinating paradox of this story is the fact that the Renaissance was based to a great extent on fiction. A taste:

The impact of Longfellow’s poem on Acadians [Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie] is clearly evident in the speeches given by the various speakers during the conventions, particularly as they made ample references to it. In fact, every one of the early Acadian nationalists seemed to consider it to be of great national value. There is no doubt that Longfellow’s Évangéline was an important source of inspiration for them.

It was in this era that the aforementioned Poirier authored the first full-length history by a person of Acadian origin. Well, it was really just a lengthy rebuttal to a (metropolitan) French historian who claimed that the Acadian settlers and the Mi’kmaq had intermarried. Poirier was insistent that they had not… for racial reasons that are very dubious by our contemporary standards.

The Age of Survivance

It was in the first half of the twentieth that the various groups of the North American francophone world came closest to sharing a common vision of themselves. Some elites dedicated themselves to the tall task of gathering people of French descent in a unifying cultural and political enterprise called survivance. That spirit was best captured by the three Congrès de la langue française held in 1912, 1937, and 1952. Though each was held in Quebec City—and could be seen as a pretext for the projection of Quebec culture and power—these conventions drew delegates from Western Canada, Ontario, Louisiana, New England, and the old Acadian homeland.

The online collections of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec never cease to amaze me by their scope, and it just so happens that they include proceedings of the 1937 event. The volumes on the French language and education include valuable studies on the Maritime provinces and Louisiana and are well worth checking out. (Note that in true French fashion, the table of contents is at the end of these volumes; click on “Éléments” on the right-hand side to access the different volumes.) Other interesting texts on the state of Acadian culture appear in this synopsis of the 1912 congress.

Revival, Again

In the 1960s, New Brunswick, where the largest group of Acadian people were concentrated, had their own “Quiet Revolution.” Five days after Quebeckers went to the polls and ended sixteen years of Union Nationale rule, their compatriots in New Brunswick chose Louis Robichaud as their premier—the first Acadian elected to that position. Robichaud implemented a program of moderate reform that was notably calculated to close disparities between French and English speakers in the province.

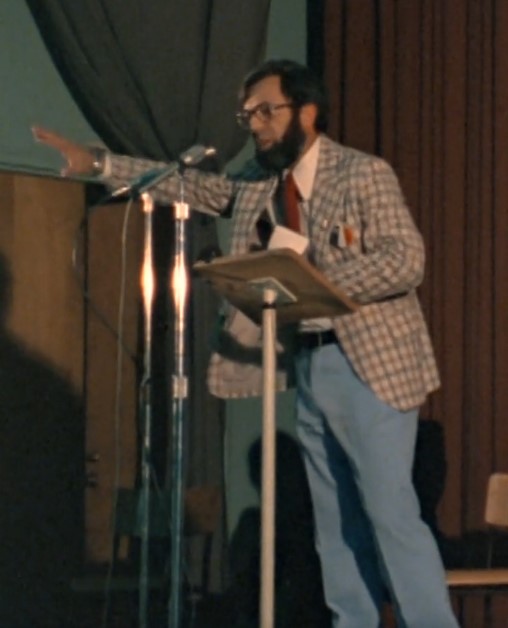

In the following decade, a new generation (in political terms) sought a whole new destiny for the Acadians of New Brunswick. The Parti Acadien embodied the hopes of these “young turks.” Inspired by Quebec nationalism, they planned to leave not Confederation, but New Brunswick, and thus to form an eleventh province that would, like Quebec, have a French majority. At the center of that story was politician—and Catholic priest—Armand Plourde, who, from his home in Kedgwick, nearly won election to the provincial legislature. This film by Denis Godin provides an insider’s view of Plourde’s campaign.

The above—a very small sample of internet resources on the subject—is of course very Canada-heavy. So much of the Acadian story lies in the United States. To bring the narrative to the present, I recommend this video on efforts to preserve Acadian culture in a predominantly English-speaking setting. See also the following interview with the incomparable Jo-El Sonnier, with special kudos to Télé-Louisiane.

For researchers planning a deep-dive in all matters of Acadian history, I recommend the three-part guide compiled by Andrea Eidinger and Stephanie Pettigrew—see Part I, Part II, and Part III.

Leave a Reply