Mark your calendars! On May 18, at 2 p.m. (Eastern time), I will be speaking on Franco-American religious battles for the Franco-American Centre at the University of Maine. The link will be accessible through the Centre shortly before the event. Then, on May 21, at noon, I will deliver a lecture as part of the Vermont Historical Society’s Third Thursday program. At the moment, the plan is to offer access on Zoom. This talk is titled “The Other Franco-Americans: Tracing French-Canadian Settlement in Vermont.” You can find more info on the VHS’s social media pages.

As some readers know, I have a book under contract with the University Press of Kansas. Of course, due to conference presentations, essays I’ve published, and this blog, people generally assume that this will be a work of Franco-American history. I suppose I have earned the quizzical looks I get when explaining that my Ph.D. dissertation and this forthcoming book are studies of John F. Kennedy’s time in office.

UPK publishes big titles in presidential studies and U.S. politics and I am very excited to have this opportunity to share my research beyond the dissertation-reading public—an audience which, I hear, is actually a mere figment of my imagination. I will avoid giving too much away—I have closely guarded the “big reveals”—but suffice it to say that this is a project on the central place of religion in the political activism of the early 1960s.

Yes, yes, but what about Franco-Americans? Since it has taken nearly six years to get to this point with my Kennedy project, the book on Francos that many of you are expecting from me should appear either in the spring or summer of 2038. I have no qualms about abusing a sense of anticipation.

One book did lead me to think more seriously about the other, or at least about what books on Franco-American history look like. For context, most works of Franco history fall into one of the following categories:

1) Biographies: We might take Janet Shideler’s work on Camille Lessard-Bissonnette as an example. In the last generation, biographies have been quite few. There are recent works on Calixa Lavallée and Eva Tanguay, Quebec-born personalities who claimed success in the U.S., but these are not essentially depictions of individuals as Franco-Americans. Older works, for their part, tend to veer towards hagiography.

2) Community studies: Originating in nineteenth-century parish histories, these works are perhaps the most abundant. Think of Mark Richard’s book on Lewiston, or Tamara Hareven’s on Manchester. Most of the classic unpublished dissertations of the 1970s were in fact Franco-American community studies. Arcadia and The History Press have recently produced a revival in studies addressed to a broad, non-academic audience.

3) Monographs: This type of work has a clear argument and a fairly narrow scope. Among the few books in this category are Mark Richard’s Not a Catholic Nation on the Ku Klux Klan in New England and Yukari Takai’s Gendered Passages on the changing nature of the family and gender roles through the migration process.

4) Historical surveys: These are overarching works covering a long period and vast areas without the binding argument found in monographs. The idea is to offer an histoire totale that isn’t necessarily cohesive. After all, the past itself seldom is. Starting with Robert Rumilly’s Histoire des Franco-Américains published in 1958, I count six surveys or syntheses, authored chronologically by Rumilly, Gerard Brault, François Weil, Armand Chartier, Yves Roby, and David Vermette.[1] All of these authors offer themes and patterns rather than a single unifying argument; they differ from one another by emphasizing different areas of Franco-American life.

Unmoored from the task of arguing or defending one single, central claim, the Franco-American historical survey may be the most malleable of these literary forms. Were we to ignore the author’s creative impulse, we might liken it to a giant pot into which any readily available ingredient is dumped, resulting in a somewhat incoherent dish. This is not meant as a critique, since societies and human beings tend to be pretty goshdarn incoherent, or at least complex—and that should be reflected in the literature.

Of course, we do have to take into account the author’s purpose and interests, which strongly flavor his or her work. Surveys, then, are not entirely formless. The very word survey implies that samples must be taken to achieve the overarching view. This kind of work requires shortcuts—unless it is to be utterly comprehensive and stretch to 10,000 pages. We ultimately tend to see less of specific historical actors’ individual agency, few local particularities. In exchange, the author creates a mainstream, a central experience that underwent a very clear process due to limited, verifiable factors.

The assumption of a fundamental unity and homogeneity—of a clear and near-universal pattern to bind the survey—may be a necessary evil, lest, again, this turn into a multivolume postmodern mess.

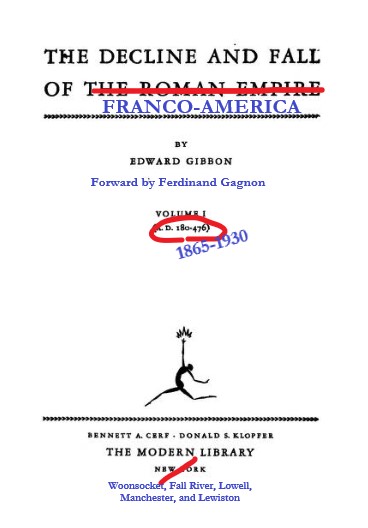

In Franco-American history, the pattern is typically offered as: Agriculture sours in Quebec, mills go up in New England, emigrants cohere in Little Canadas; Francos fight for “parish and nation” but their claims and pursuit of a distinct identity are no match for nativism and the forces of the cultural mainstream. It’s the decline and fall of the French-Canadian empire in the United States, the tale of the fallen French Canadian and reluctant American. This narrative is common to all types of studies listed above.

Literary scholar and historian Hayden White argued that there were only so many ways to tell a story, or to write history—that historians were really captives of existing literary forms. A scholar might write a romance, likely involving a heroic quest that ends with good prevailing over evil. He or she could spin events as a comedy: two groups fall apart but, after a struggle, reconcile, to the satisfaction of all. Another narrative form would be the tragedy: the fruitless struggle. At last, historians might resort to satire: the conscious recognition of the limits of human reason and human enterprises, which tends to make light of grand schemes (those of historical subjects and fellow historians alike).

In the nineteenth century, Quebec historical writing was caught between romance (the good French Catholics were providentially destined to overcome) and tragedy (political and military reversals had imperiled the French Catholic civilization in America).[2] Needless to say, this balance tended to weigh towards the former, lest French Canadians give up entirely on their religious and national aspirations. Franco-American writing inherited these two narratives: on one hand, a righteous cause, cemented by a glorious history, that was destined to prevail; on the other, the loss of faith, language, and customs due to the insurmountable cultural and political forces of the Great Republic.

Whatever their lived realities may have been, the history of Franco-Americans in the twentieth century is the story of the gradual decline of the romantic narrative.

All four types of historical writing (biographies, community studies, and so forth) tend to reflect this. If additional research undertaken in the last two decades has opened new paths, the tragic view is still prevalent, fed by inescapable nostalgia. Less recognized is the fact the sense of loss has been present for over a century. For four generations and maybe more, Franco-Americans have deplored the loss in their own time of their ethnic identity.

We need only to think of alternative narratives to see how prevalent—and apparently natural—the story of loss still is. Pitched as a comedy, Franco-American history would suggest that Americanization was and is benign; it is silly that French Canadians resisted the ambient forces of their adoptive country, for everything is well now. Pitched as a satire: the cherished ideologies and illusions of elites were ultimately impotent and had little meaning in the daily lives and decisions of Franco-Americans.

That these two narrative modes seem absurd says something about ideological presuppositions embedded in the field.

Owing to the overwhelming preponderance of tragic sentiment in the field, it is unsurprising that historians tend to focus on loss in their selection and arrangement of primary information. Whether it should be, as we refine our methods and continue to bring sources to light, is an open question. But we should be aware that these narratives are of our own making.

To be clear, narrative is essential to the historical craft; it is one way to make sense of past events, assert their relevance, and reach readers. And I am not suggesting that loss isn’t a part of the Franco-American saga. Rather, this is an invitation to approach Franco-American narratives critically, to respect the agency of the people we study, and to avoid imposing upon them a world that they would not have recognized. Hindsight is a great gift, but one that is too often abused in the interest of a usable past.

Next week: Franco-American Books: A Wish List.

[1] Chartier’s work was later translated; Roby’s was first expanded, then translated. I do not count these new editions as altogether different surveys.

[2] Elites’ identification with the society’s religious character meant that satire was not a serious option. It may be argued that conservative political leaders committed to the “two nations” theory and believing in its ultimate success might view history as a comedy of sorts; the same applies to liberals who believed in the reconciliation of French-Canadian and American ideals.

Leave a Reply